This is my introduction to a new, popular edition of four Charles Dickens novels, available in bookstores, online, and in big-box retail stores.

(ERNEST HILBERT) DICKENS, Charles. Four Novels: Tale of Two Cities, Oliver Twist, Great Expectations, and A Christmas Carol. San Diego: Baker and Taylor/Thunder Bay, 2011. Stout octavo, hardcover. $24.95. ISBN-10: 1607103125

Introduction

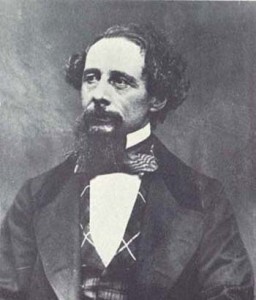

Charles Dickens was the greatest novelist of the Victorian era, and perhaps the most famous English novelist of all time. He once went so far as to describe himself as “an amazing man,” and it is true that he was exceedingly gifted. In fact, his creative powers were matched only by his ambition. He is undoubtedly the most “English” of authors after William Shakespeare, meticulously capturing the lives, locales, and affairs of his native land at a time of remarkable societal change. He invented characters that seem to leap off the page. They live on in our imaginations long after the last leaf is turned. His popularity and influence were not only unmatched in his day but absolutely groundbreaking, altering the very essence of the novel. Aside from amusing his readers—something he never failed to do—Dickens had a real impact on the world around him. Energized by ideas of social reform, he was both a humanistic novelist and a true humanitarian. He supported the abolition of slavery and founded a home for “fallen” women, Urania College in London, with the help of heiress Angela Burdett Coutts. Novels such as Oliver Twist are works of fierce social commentary that helped to alter public opinion, thus steering the course of legislative reform. As novelist Jane Smiley wrote in her biography of the author, Dickens “never forgot that his fame gave him an unusual opportunity to comment upon and influence political events.”

Born into a family of modest means in 1812, when Napoleon still ruled much of Europe, Dickens would be greeted with unprecedented accomplishment as a novelist in a century that saw the British Empire attain its greatest reach, spanning the globe and dominating international commerce. The Industrial Revolution swung into full force in England, producing magnificent wealth but also horrendous and even harmful conditions for workers. The Victorian era roughly coincided with the Pax Britannica, or Peace of Britain—the era between Wellington’s triumph over Napoleon at Waterloo in 1815 and the first shots of World War I in 1914—when Britain remained free of the threat of outside invasion. Railways and popular newspapers changed the very fabric of daily life for the English, and the Elementary Education Act of 1870 promised literacy for all. It was an era of rapid political and scientific adjustment unseen in earlier centuries: Charles Darwin embarked on his groundbreaking scientific travels on the HMS Beagle in 1831, and Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels published The Communist Manifesto in 1848 (Marx moved to London the following year and remained there for the rest of his life).

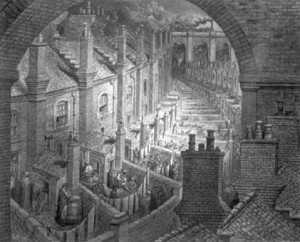

With the first of the Reform Acts (measures to enfranchise new voters) in 1832 and Queen Victoria’s ascension to the throne five years later, the Victorian era began in earnest, bringing with it a bewildering combination of affluence and deprivation, progress and reaction. London swelled as agrarian workers poured in to find work, growing from roughly one million inhabitants in 1800 to more than six million by the end of the century. Buildings were black with soot from coal-fire stoves, and streets were filthy. Raw sewage spewed directly into the river Thames, which flows directly through the city. In fact, Dickens’s London would appear to us a sprawling third-world city, crammed with beggars, plagued by crime, and fouled by pollution. Graveyards overflowed, and bodies were buried on top of one another. Contemporary accounts describe the stench as horrific. As Dickens biographer Peter Ackroyd has written, “If a late twentieth-century person were suddenly to find himself in a tavern or house of the period, he would be literally sick—sick with the smells, sick with the food, sick with the atmosphere around him.”

From Rags to Riches

Charles’s father, John Dickens, worked for a time as a clerk in the Royal Navy Pay Office in Portsmouth, briefly affording his family a comfortable life. As a boy, Charles read the episodic adventure novels of Tobias Smollett and Henry Fielding, which later inspired his own style of writing. He retained fond memories of early boyhood, but such times would not last. As Michael Slater has written, “During the first six years of Dickens’s life his parents moved house no fewer than five times and it seems likely that this restlessness affected Dickens in his later life when he seemed to have some sort of need for constant changes of environment.” Sadly, his father’s penchant for living beyond his means ended in his arrest and consignment to Marshalsea debtor’s prison in London. The rest of the family eventually joined him there with the exception of Charles, who was sent to live with a family friend in the Camden Town section of North London.

Charles’s father, John Dickens, worked for a time as a clerk in the Royal Navy Pay Office in Portsmouth, briefly affording his family a comfortable life. As a boy, Charles read the episodic adventure novels of Tobias Smollett and Henry Fielding, which later inspired his own style of writing. He retained fond memories of early boyhood, but such times would not last. As Michael Slater has written, “During the first six years of Dickens’s life his parents moved house no fewer than five times and it seems likely that this restlessness affected Dickens in his later life when he seemed to have some sort of need for constant changes of environment.” Sadly, his father’s penchant for living beyond his means ended in his arrest and consignment to Marshalsea debtor’s prison in London. The rest of the family eventually joined him there with the exception of Charles, who was sent to live with a family friend in the Camden Town section of North London.

What may be the most influential event of the author’s life occurred at this time. Dickens enjoyed his education at William Giles’s School in Chatham, but after his father’s imprisonment he was obliged to begin work at the tender age of twelve in order to help support his family. He was dispatched to Warren’s Blacking Warehouse, where he worked grueling ten-hour days applying labels to bottles of boot polish. Dickens described the factory to his friend John Forster, author of The Life of Charles Dickens, the first of many biographies of the author:

It was a crazy, tumble-down old house, abutting of course on the river, and literally overrun with rats. Its wainscoted rooms, and its rotten floors and staircase, and the old grey rats swarming down in the cellars, and the sound of their squeaking and scuffling coming up the stairs at all times, and the dirt and decay of the place, rise up visibly before me, as if I were there again.

To make matters worse, the young Dickens was displayed to passersby in a window, a cruel parody of his later aspiration to appear on the stage. The extraordinarily bright boy was crushed by this experience, and there is little doubt it sparked his lifelong commitment to the reform of working conditions for the poor. It would also inspire him to write about the underprivileged—laborers, servants, beggars, thieves—who rarely figured in the literature of the age, remaining entirely invisible as they had in novels of a previous generation, such as those of Jane Austen. Dickens might have spent years in the factory if not for two strokes of fate: the death of his paternal grandmother, who left a modest sum to his father, and the passage by Parliament of the Insolvent Debtors Act, which allowed the Dickens family to leave Marshalsea and relieve young Charles from his position at Warren’s Blacking. Dickens enrolled in Wellington House Academy in North London, but his mother, Elizabeth Dickens, contemplated sending young Charles back to the blacking factory. He later wrote: “I never afterwards forgot, I never shall forget, I never can forget, that my mother was warm for my being sent back.” It is very likely that Charles never fully forgave his father’s spendthrift ways or his mother’s willingness to see her son sent to work for the family at such a young age.

In 1827, Dickens’s mother partly redeemed herself when she helped to place him as a law clerk at the firm of Ellis and Blackmore. This busy and demanding post soon led to another as a court stenographer. His experience with the firm provided him with material he would use again and again in his novels. All three full-length novels in this volume contain famous courtroom scenes: Oliver Twist faints from illness before a judge when accused of the theft of a book actually stolen by the Artful Dodger; Charles Darnay is falsely accused of spying for the French in A Tale of Two Cities; and the stern lawyer Mr. Jaggers and his charming clerk John Wemmick play pivotal roles in Great Expectations. Even the short novel A Christmas Carol can be read as an indictment and eventual acquittal of its central figure, Ebenezer Scrooge, on charges of hard-heartedness. Dickens would have also witnessed grisly hangings at Newgate Prison, near the Old Bailey, the central courtrooms of London. All four novels end with an execution of one kind or another: Oliver Twist with that of the child-exploiter Fagin at Newgate; A Tale of Two Cities with that of Sydney Carton in the Place du Revolution; Great Expectations with that of Magwitch, who dies in prison before he may be hanged; and even A Christmas Carol contains an execution of sorts, when Scrooge is shown his own cold, unvisited grave by the ghost of Christmas Yet to Come.

The Early Achievements

In 1833, at the age of 21, Dickens published his first story in the Monthly Magazine and began work as a journalist, covering parliamentary debates and election campaigns for the Morning Chronicle, another experience that would serve him well as a novelist. He began composing “sketches” of scenes and characters from his daily routines. These would be collected into his first book, Sketches by Boz, in 1836 (“Boz” was his occasional pen name). Around this time, Dickens entertained thoughts of a possible career as an actor. As fate would have it, he took ill on the day of his audition at the Lyceum Theatre and failed to appear. Afterward, he settled on a career as a novelist, though he never entirely surrendered dreams of the stage.

Dickens truly enjoyed acting. He appeared in amateur theatricals throughout his life, always to encouraging reviews. He enjoyed mimicry and performed wildly entertaining impressions for friends. When crafting his novels, he stood before a mirror to sound out voices and test facial expressions. This goes some way to explaining his amazing ability to create such lifelike characters. In fact, outside of Shakespeare, it is hard to think of an English writer who generated such an astonishing array of characters from all social ranks and circumstances. He sometimes wrote for the stage, though his plays were never met with the enthusiasm that attended his novels, and they are largely forgotten. Later in life, he became a popular public reader of his own novels, assuming voices and acting out whole scenes single-handedly. For example, Jane Smiley writes that he gave a reading “in Bradfordthat attracted 3,700 people, followed by another in London. He read A Christmas Carol each time and used the story and the time of year and the occasions to promote the sort of openhearted generosity that had always been important to him. . . . It was one thing [for Dickens] to act in a play or a farce, in character and often speaking the words of another author. It was quite different to say his own words, passing through the personae of characters he himself had created, giving voice and action to his own inner life.” His tours of England,Scotland,Ireland, and America earned substantial sums of money for his family and a variety of causes he championed.

Dickens truly enjoyed acting. He appeared in amateur theatricals throughout his life, always to encouraging reviews. He enjoyed mimicry and performed wildly entertaining impressions for friends. When crafting his novels, he stood before a mirror to sound out voices and test facial expressions. This goes some way to explaining his amazing ability to create such lifelike characters. In fact, outside of Shakespeare, it is hard to think of an English writer who generated such an astonishing array of characters from all social ranks and circumstances. He sometimes wrote for the stage, though his plays were never met with the enthusiasm that attended his novels, and they are largely forgotten. Later in life, he became a popular public reader of his own novels, assuming voices and acting out whole scenes single-handedly. For example, Jane Smiley writes that he gave a reading “in Bradfordthat attracted 3,700 people, followed by another in London. He read A Christmas Carol each time and used the story and the time of year and the occasions to promote the sort of openhearted generosity that had always been important to him. . . . It was one thing [for Dickens] to act in a play or a farce, in character and often speaking the words of another author. It was quite different to say his own words, passing through the personae of characters he himself had created, giving voice and action to his own inner life.” His tours of England,Scotland,Ireland, and America earned substantial sums of money for his family and a variety of causes he championed.

In 1836, Dickens married Catherine Hogarth. Together they reared ten children and spent many years in what most believe to be domestic contentment, though by the end they split acrimoniously, much to the chagrin of both Dickens’s friends and the public at large. Family life was important for Dickens, and he suffered terribly as his marriage came apart. One can feel the unquenchable desire for domestic happiness throughout his novels: The orphan Oliver seeking the protection and love he was denied in the workhouse; Doctor Alexandre Manette released from years of imprisonment to his daughter’s care; young Pip struggling to create the semblance of a family with his cruel sister and avuncular brother-in-law; and even Scrooge, as he yearningly peers in on the humble Christmas feast of his clerk Bob Cratchit.

Dickens was a flamboyant dresser, a bit of a dandy, and was a favorite at parties, where his exuberant personality held sway. From a young age he found himself constantly in demand as the celebrated writer of the day. He kept a pet raven, named Grip, which he had stuffed upon its death (after King George IV stuffed his pet giraffe, such morbid practices became all the rage in England). Grip appeared as a talking raven in Dickens’s 1841 novel Barnaby Rudge, and many believe this inspired Edgar Allan Poe to pen his famous poem “The Raven” in 1845. (Grip, surely the most famous raven of his or any other time, now resides at the Free Library of Philadelphia.) Dickens enjoyed great adulation from his fiercely devoted readers. He packed large auditoriums on his reading tours and was cheered on the streets ofNew York City. He became a household name, as did many of his most famous characters.

Although earlier publishing contracts failed to satisfy him financially, fame allowed Dickens to dictate his own terms, and he eventually became quite wealthy from his novels. He owned many properties and traveled widely, constantly in need of a change of scenery. He was, in some ways, one of the first modern celebrities. His fame was spectacular, his followers almost hysterical for a glimpse of the man himself. He was an artist, but also very much a man of the world. Perhaps his proudest possession, one imbued with great symbolic significance, was Gads Hill Place in Higham, Kent. When Dickens was a young boy, his father pointed to the country home, probably at random, and told him that if he worked hard he could someday own a home just like it. When Dickens saw it for sale in 1856, he could not resist. He purchased it and soon added much-needed bookcases. He entertained equally famous friends there, including Hans Christian Andersen and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. It served as a tangible emblem of artistic and financial success—things craved by the man who once toiled in a blacking factory.

A Prolific Career

Over the course of his life, Dickens published fifteen novels (the last, The Mystery of Edwin Drood, was left unfinished upon his death, so we will never know “who did it”) along with five shorter Christmas novels, including A Christmas Carol. He also found time to edit several periodicals—Master Humphrey’s Clock (1840–41), Household Words (1850–59), and All the Year Round (1859–70)—as well as compile nonfiction volumes such as American Notes (1843) and Pictures from Italy (1846). His novels appeared in serial form before book publication, either in periodicals or, more often, as individual chapters for sale at newsstands. Interest in a story line could be gauged by how well each chapter sold. Typically, sales increased over time as word of enticing plots spread and curiosity mounted. This represented a new way of selling as well as a new way of telling. Readers were gripped by a story that was still being written. Dickens changed story lines based on audience reactions, since he himself did not yet know how a story would progress or what fate a character might meet, even as the whole of London was abuzz with a novel’s early chapters. Installments regularly ended in cliff-hanger fashion, leaving his fans eager for more. It is said that American readers waited on the docks for boats carrying new installments of The Old Curiosity Shop, on one occasion pleading to know “is Little Nell dead?”

Over the course of his life, Dickens published fifteen novels (the last, The Mystery of Edwin Drood, was left unfinished upon his death, so we will never know “who did it”) along with five shorter Christmas novels, including A Christmas Carol. He also found time to edit several periodicals—Master Humphrey’s Clock (1840–41), Household Words (1850–59), and All the Year Round (1859–70)—as well as compile nonfiction volumes such as American Notes (1843) and Pictures from Italy (1846). His novels appeared in serial form before book publication, either in periodicals or, more often, as individual chapters for sale at newsstands. Interest in a story line could be gauged by how well each chapter sold. Typically, sales increased over time as word of enticing plots spread and curiosity mounted. This represented a new way of selling as well as a new way of telling. Readers were gripped by a story that was still being written. Dickens changed story lines based on audience reactions, since he himself did not yet know how a story would progress or what fate a character might meet, even as the whole of London was abuzz with a novel’s early chapters. Installments regularly ended in cliff-hanger fashion, leaving his fans eager for more. It is said that American readers waited on the docks for boats carrying new installments of The Old Curiosity Shop, on one occasion pleading to know “is Little Nell dead?”

With great success, though, came disappointments. Dickens’s private life was under terrible scrutiny at all times, especially after he finally separated from his wife. He learned that pirated copies of his work were sold without his permission, particularly in America, where he, as a British subject, was not protected (the US Copyright Acts of 1790 and 1831 did not prohibit the copying of foreign authors). Also, the strain of touring and the frantic pace of writing against deadlines began to take a toll on his health. Strained almost to the point of breaking, Dickens embarked on a series of self-proclaimed “farewell” readings for his fans in the late 1860s. In 1870, while working on his last novel at his beloved Gads Hill, he suffered a stroke and died. Against his wishes, he was interred at Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey alongside the likes of Geoffrey Chaucer, John Dryden, and Samuel Johnson.

An Advocate for the Poor

Dickens’s legacy is keenly felt today. His books are as popular as ever, and they have never gone out of print. Countless movies and television series have been adapted from them. Dickens festivals are held around the world. He may be the only novelist to have an amusement park based on his works. Dickens World in Chatham, where Dickens lived parts of his life, is a privately funded theme park that boasts Europe’s longest indoor ride, the Great Expectations boat trip. Other attractions include the Haunted House of Ebenezer Scrooge and Fagin’s Den, a play area (watch out, Oliver!). Dickens has only grown in popularity in the last century and a half, even appearing as a selection of Oprah Winfrey’s book club, and there is no sign his fame will diminish anytime soon.

Oliver Twist is a novel of injustice, compassion, and charity. It is Dickens’s second, begun when he was only 25. It was his first true best-seller, appearing in monthly installments between February 1837 and April 1839. It is a severe critique of English society and law (most notably the Poor Law, which provided meager provisions for orphans), packed with sarcasm, bleak humor, and, of course, plenty of action and suspense. It was the first major English novel told from the perspective of a child. Readers thrilled with fear for Oliver, an orphan raised in a workhouse, where inmates have grown accustomed to ritual deprivation and abuse. Oliver’s plaintive request for a second meager helping of gruel, “Please, sir, I want some more,” is surely one of the most resonant lines in any novel. The simple request, made on behalf of another boy, incites disbelief and then rage on the part of his well-fed keepers, who lend him out as an apprentice to the undertaker Mr. Sowerberry, who in turn lends him out as an extra “mourner” for children’s funerals. Mrs. Sowerberry, the undertaker’s wife, takes an instant dislike to Oliver and proceeds to all but starve him. After Oliver is goaded into a rage by taunts from a fellow apprentice, he is beaten by the hypocritical Mr. Bumble, a parish beadle, and runs away to London, where he is taken in by the evil Fagin. A professional thief and fencer, Fagin lures homeless boys into a sinister facsimile of family life, where they are cared for, to a point, in return for serving as pickpockets and lookouts for Fagin’s criminal syndicate. Other boys in Fagin’s “family,” including the Artful Dodger, attempt, unsuccessfully, to attract Oliver to their criminal ways:

What was Oliver’s horror and alarm as he stood a few paces off, looking on with his eyelids as wide open as they would possibly go, to see the Dodger plunge his hand into the old gentleman’s pocket, and draw from thence a handkerchief! To see him hand the same to Charley Bates; and finally to behold them, both, running away round the corner at full speed.

When the other boys steal the handkerchief of the gentleman Mr. Brownlow, Oliver, though an innocent bystander, is chased and captured. Sent before a judge, Oliver faints from exhaustion but is acquitted by eyewitness testimony. Mr. Brownlow, who believes Oliver to be innocent, takes him home, where he cares for the orphan with help from his housekeeper, Mrs. Bedwin. Throughout the novel, Oliver is torn between these two families, that of the evil Fagin and his murderous accomplice Bill Sikes on the one hand, and that of the gentle and charitable Mr. Brownlow and Mrs. Bedwin on the other.

Oliver Twist mixes dynamic realism not common to English readers of the time with unpitying lampoons of the types of men who would exploit the young, such as the fatuous Mr. Bumble. Dickens’s terrifying descriptions of the conniving Fagin and Sikes excited readers like nothing that had come before, and when Dickens later reenacted Sikes’s brutal murder of his moll Nancy, audiences reacted with shock but were drawn irresistibly to hear it again:

She staggered and fell: nearly blinded with the blood that rained down from a deep gash in her forehead; but raising herself, with difficulty, on her knees, drew from her bosom a white handkerchief—Rose Maylie’s own—and holding it up, in her folded hands, as high towards Heaven as her feeble strength would allow, breathed one prayer for mercy to her Maker.

It was a ghastly figure to look upon. The murderer staggering backward to the wall, and shutting out the sight with his hand, seized a heavy club and struck her down.

The novel’s portrayal of life in London’s slums and workhouses shocked readers no less than Nancy’s murder, laying bare the appalling conditions of the poor to a middle class audience that had little knowledge of such things. The battle played out for possession of Oliver, the naive orphan, is actually a battle for the soul of England itself, waged between those who would corrupt and exploit and those who sought to enlighten and improve.

The Spirit of Christmas

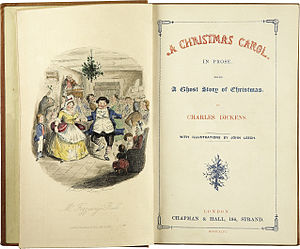

A Christmas Carol, a fable of redemption, is the first of five short Christmas novels Dickens published annually in the 1840s, though it is the only one that remains familiar to most readers today. It was published six years into Queen Victoria’s reign and was extremely popular at the time (pirating, a common practice in the era, began directly after publication; Dickens, protected under British copyright law, pursued the pirates with cases in the Court of Chancery; after one victory, Dickens exclaimed, “The pirates are beaten flat!”). In fact, its popularity has never waned. A Christmas Carol is a departure from Dickens’s customary realistic style and can be best understood as a parable dressed as a ghost story. The slim novel did much to revive the celebration of Christmas in both England and America, though the trend it spurred along was already underway. There was a common nostalgia for Christmas in the Victorian age, roused by Prince Albert’s introduction of the Christmas tree from Germany in 1841 (he was born to the German family of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld) and the Christmas card in 1843, along with the publication of several collections of Christmas carols, such as William B. Sandys’s Selection of Christmas Carols, Ancient and Modern (1833). As peculiar as the yuletide ghost story might seem, it fully expresses Dickens’s characteristic sympathy for the poor and his disdain for those who seek to take advantage of them.

A Christmas Carol, a fable of redemption, is the first of five short Christmas novels Dickens published annually in the 1840s, though it is the only one that remains familiar to most readers today. It was published six years into Queen Victoria’s reign and was extremely popular at the time (pirating, a common practice in the era, began directly after publication; Dickens, protected under British copyright law, pursued the pirates with cases in the Court of Chancery; after one victory, Dickens exclaimed, “The pirates are beaten flat!”). In fact, its popularity has never waned. A Christmas Carol is a departure from Dickens’s customary realistic style and can be best understood as a parable dressed as a ghost story. The slim novel did much to revive the celebration of Christmas in both England and America, though the trend it spurred along was already underway. There was a common nostalgia for Christmas in the Victorian age, roused by Prince Albert’s introduction of the Christmas tree from Germany in 1841 (he was born to the German family of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld) and the Christmas card in 1843, along with the publication of several collections of Christmas carols, such as William B. Sandys’s Selection of Christmas Carols, Ancient and Modern (1833). As peculiar as the yuletide ghost story might seem, it fully expresses Dickens’s characteristic sympathy for the poor and his disdain for those who seek to take advantage of them.

Dickens wrote A Christmas Carol in a mere six weeks, in order to have it ready for the season (his publisher, Chapman & Hall, rushed it out on December 19, 1843). He divided it into five “staves,” or musical stanzas, in keeping with its title, describing the spiritual journey of Ebenezer Scrooge from callous miser to a warmhearted benefactor. Scrooge is one of Dickens’s most famous characters: To this day the word “Scrooge” conjures the image of a person lacking Christmas spirit. Scrooge’s love of money and marked lack of interest in others make him persona non grata right from the start:

Nobody ever stopped him in the street to say, with gladsome looks, “My dear Scrooge, how are you? when will you come see me?” No beggars implored him to bestow a trifle, no children asked him what it was o’clock, no man or woman ever once in all his life inquired the way to such and such a place, of Scrooge. Even the blindmen’s dogs appeared to know him; and when they saw him coming on, would tug their owners into doorways and up courts.

Even dogs avoid the man. Amazingly, Scrooge prefers it that way: “But what did Scrooge care? It was the very thing he liked.” After refusing his nephew’s invitation to Christmas dinner, and only reluctantly releasing his dutiful employee Bob Cratchit for one day’s holiday leave, Scrooge returns home alone to be greeted by the first of four ghosts that haunt him that night. His business partner, Jacob Marley, who worked himself to death years before, appears first as a warning face on Scrooge’s door knocker and then in full after Scrooge locks himself inside. Marley’s ghost drags a chain of clerical instruments behind him even in death:

The same face: the very same. Marley in his pigtail, usual waistcoat, tights and boots; the tassels on the latter bristling, like his pigtail, and his coat-skirts, and the hair upon his head. The chain he drew was clasped about his middle. It was long, and wound about him like a tail; and it was made (for Scrooge observed it closely) of cash-boxes, keys, padlocks, ledgers, deeds, and heavy purses wrought in steel. His body was transparent; so that Scrooge, observing him, and looking through his waistcoat, could see the two buttons on his coat behind.

Even this dreadful scene contains some of Dickens’s trademark comic sparkle: “Scrooge had often heard it said that Marley had no bowels, but he had never believed it until now.”

Marley tells Scrooge that he will be visited by three ghosts upon the stroke of one: “‘Without their visits,’ said the Ghost, ‘you cannot hope to shun the path I tread,’” the path, that is, of the wandering dead. The first ghost, Christmas Past, transports Scrooge from his bed to scenes of his youth, when, as a young man, he was tender, hopeful, and kind, before he dedicated himself completely to work. Scrooge begins his positive transformation almost immediately, regretting that there “was a boy singing a Christmas Carol at my door last night. I should like to have given him something.” The second ghost, Christmas Present, sweeps Scrooge off to witness how others celebrate Christmas (stopping at a miner’s shack, briefly on a ship at sea, and at a lighthouse), including his impoverished employee Bob Cratchit, whose crippled son, Tiny Tim, strains to enjoy the holiday with his family, declaring, “God bless us every one.” The third spirit, the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come, is a “mysterious presence” that fills Scrooge “with a solemn dread.” The grim form presents Scrooge with his own forlorn and unvisited grave. This final vision, of an unredeemed death and squandered life, convinces Scrooge to change, and he beseeches the spirit to “assure me that I yet may change these shadows you have shown me, by an altered life.”

Transformed at last, Scrooge wakes to learn only a single night has passed and that it is Christmas morning. He sends a prize turkey as an anonymous gift to Bob Cratchit’s family and spends Christmas day in the affectionate company of his nephew’s family. A Christmas Carol ends on a jubilant chord, drawing the reader in as well: “It was always said of him, that he knew how to keep Christmas well, if any man alive possessed the knowledge. May that be truly said of us, and all of us! And so, as Tiny Tim observed, God bless Us, Every One!”

A Student of Revolution

A Tale of Two Cities is a historical epic of loyalty, sacrifice, and revenge. It begins and ends with two of the most famous passages in all of English literature. To properly summon the sense of uncertainty heralded by the French Revolution, Dickens starts with a series of baffling paradoxes that nonetheless define both the age and the unbridgeable divide between Paris and London, the two cities of the title:

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way . . .

The novel concludes with the heroic and consoling words of Sydney Carton, who sacrifices himself to the guillotine in order to permit Charles Darnay, a blameless man, to escape Parisand return to London with his family. Redeeming his otherwise depraved and parasitical life, Carton whispers in “a tender and a faltering voice” that “it is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest that I go to than I have ever known.”

The powerful drama of these passages matches the grand historical tone of the entire novel. A Tale of Two Cities is one of only two historical novels written by Dickens (the other is Barnaby Rudge, published in book form in 1841, another tale of mobs and riots, set during the anti-Catholic Gordon Riots). The sense of tension and unease begins right from the start, on the road from London to Dover, where passengers embark for France:

The Dovermail was in its usual genial position that the guard suspected the passengers, the passengers suspected one another and the guard, they all suspected everybody else, and the coachman was sure of nothing but the horses.

Not long after, across the channel, in front of Madame DeFarge’s St. Antoine Wine Shop in Paris, a wine cask “tumbled out with a run, the hoops had burst, and it lay on the stones just outside the door of the wine-shop, shattered like a walnut-shell,” an accident which inaugurates a mad sprawl by passersby, who fall to their knees to lap the wine from the cobblestones. This symbolically bloody omen is emphasized when “one tall joker so besmirched, his head more out of a long squalid bag of a nightcap than in it, scrawled upon a wall with his finger dipped in muddy wine-lees—BLOOD.”

A Tale of Two Cities is one of the most popular novels of all time, and it elated Victorian readers no less than their twentieth-century counterparts. Although moments of high melodrama may occasionally strike modern readers as unnecessarily sentimental, the descriptions of mob violence are among the finest of their kind. An ominous mood permeates the novel, and one fully comprehends the sense of looming disaster felt by those who lived through the French Revolution on both sides of the English Channel. Dickens based some of the scenes on Thomas Carlyle’s 1837 book The French Revolution: A History, but he populates the historical landscape with his uniquely human characters. Dickens’s descriptions of societal disorder and political hysteria in a city beset by spies, traitors,informants, tyrants, and assassins are no less fresh today than they were when he wrote them in the mid-nineteenth century.

Dickens was almost certainly moved by sympathy for the poor and exploited of Paris—no less than he was for those of London—yet he does not advocate revolution, certainly not of the chaotic and bloody variety that detonated in France. He preferred reasonable movement toward parliamentary reform over time. He was a humanitarian, after all, and his compassion is realized through the strength of his characters, distinct and memorable individuals who stand out from mobs and crowds. Throughout A Tale of Two Cities, Dickens views the revolutionary fervor and accompanying violence as a peculiarly French condition. Although much of the English monarchy’s once-absolute power had been dissipated by the 1688 Glorious Revolution, which shifted large powers to Parliament, the French aristocracy knew no checks on its power until it was annihilated at the hands of revolutionaries. Though Dickens instinctively sympathizes with the French peasantry, subject to hardships, shortages, and arbitrary abuses—including imprisonment and murder—at the hands of the Ancien Régime, he seems similarly chilled by the rampant paranoia and unquenchable lust for revenge exhibited by the mobs that seize control of the city.

The guillotine itself is brought to life. Carlyle saw it as a function of the crazed new state: “The Guillotine, we find, gets always a quicker motion, as other things are quickening. The Guillotine, by its speed of going, will give index of the general velocity of the Republic.” Dickens lavishes even greater, and more detailed, attention to the deadly instrument:

Every day, through the stony streets, the tumbrels now jolted heavily, filled with Condemned. Lovely girls; bright women, brown-haired, black-haired, and grey; youths; stalwart men and old; gentle born and peasant born; all red wine for La Guillotine, all daily brought into light from the dark cellars of the loathsome prisons, and carried to her through the streets to slake her devouring thirst.Liberty, equality, fraternity, or death;—the last, much the easiest to bestow, O Guillotine!

There is something oddly theatrical about the bloodshed that unfolds on the streets of Paris. The assault upon the Bastille, and its liberation, seem more symbolic than anything else, given that only seven prisoners were held within. Likewise, the daily passage of the tumbrels, carts that carried the condemned, and the grisly beheadings in the Place du Revolution, attended by audiences eager for a show—many of whom reserved seats—seems bizarrely staged by the revolutionaries.

The Master of Character Development

As with all of his novels, Dickens created minor characters for A Tale of Two Cities every bit as striking as the principal ones. It is hard to forget the morbid endeavors of Jerry Cruncher, messenger for Tellson’s Bank, who steals off to ply his second trade as a resurrection man, or body snatcher, exhuming recently interred corpses to sell to medical students, a highly illegal but much-demanded trade. Equally memorable is the stout, ruddy Englishwoman Mrs. Pross, who proudly declares, “I am a Briton,” as she bravely stands off against the menacing Madame DeFarge, refusing to back down even at the threat of death.

Yet it is the primary characters who drive the story. The frail Dr. Manette is the central victim of the novel. Cast into the Bastille by a letter de cachet—an anonymous denunciation by a nobleman—he spends eighteen torturous years secretly imprisoned in solitary confinement, which deranges him to such an extent that he forgets who he is and replies only “105 North Tower” when asked his name. His daughter, Lucie—a figure so pure as to challenge credulity—rescues him when he is “recalled to life” after being released from the prison where it was believed he had died. With help from the Englishman Jarvis Lorry of Tellson’s Bank, Lucie brings Dr. Manette to London and nurses him to some semblance of mental health, where he takes his place at the center of a loving family in SoHo (London, sometimes populated by spies and riffraff, remained infinitely safer than the Paris of Robespierre’s Reign of Terror). The Manettes embody quiet family life, the basis of a moderately ordered civil society, one rendered impossible across the channel by ancient oppression and radical retribution.

Gentle Lucie’s foil is the frightening Madame DeFarge, who plots rebellion and assassination from the St. Antoine Wine Shop. Driven mad with hatred for decadent French aristocracy, Madame DeFarge becomes a cold-blooded and utterly unreasonable angel of death, bent on endless slaughter. It becomes impossible to pity her, despite the terrors once inflicted upon her and her family. Charles Darnay, though he turned his back on his demonic uncle, Marquis St. Evrémonde, is eventually sentenced to death in Paris for his family name and his uncle’s crimes against the peasantry. The last-minute swap in the cell before the execution has become one of the most enduring moments in the novel: Darnay, an innocent man, escapes the insatiable “justice” of the revolution through deception, and Syndey Carton, through the ultimate sacrifice, finally finds meaning.

The Prince of Perception

Great Expectations is a novel of aspiration, remorse, and friendship. It first appeared in installments in the magazine All the Year Round in 1860 and 1861, and it is one of Dickens’s most mature novels, reflecting a level of sophistication and subtlety sometimes lacking in earlier works. Like Oliver Twist, it begins with a young orphan, Pip, although Great Expectations, unlike Oliver Twist, proceeds to follow Pip’s growth into adulthood, tracing his efforts to meet the “great expectations” placed upon him. The opening scene gives us Pip, a boy of seven, visiting the grave of his parents on Christmas Eve. He is suddenly seized by the monstrous escaped convict Magwitch, who demands that Pip pilfer scraps of food and drink from his home for him:

Great Expectations is a novel of aspiration, remorse, and friendship. It first appeared in installments in the magazine All the Year Round in 1860 and 1861, and it is one of Dickens’s most mature novels, reflecting a level of sophistication and subtlety sometimes lacking in earlier works. Like Oliver Twist, it begins with a young orphan, Pip, although Great Expectations, unlike Oliver Twist, proceeds to follow Pip’s growth into adulthood, tracing his efforts to meet the “great expectations” placed upon him. The opening scene gives us Pip, a boy of seven, visiting the grave of his parents on Christmas Eve. He is suddenly seized by the monstrous escaped convict Magwitch, who demands that Pip pilfer scraps of food and drink from his home for him:

A fearful man, all in coarse grey, with a great iron on his leg. A man with no hat, and with broken shoes, and with an old rag tied round his head. A man who had been soaked in water, and smothered in mud, and lamed by stones, and cut by flints, and stung by nettles, and torn by briars; who limped, and shivered, and glared and growled; and whose teeth chattered in his head as he seized me by the chin.

Magwitch is one of the great villains of Dickens’s novels, but he is also the most complex, as readers discover later in the novel. Magwitch is eventually recaptured and returned to the “hulk,” or prison ship, where he is jailed off the coast, but Pip has been inducted into an adult world of suspicion and fear from which he is never again entirely free.

The genial Pip is raised by his bad-tempered adult sister and Joe Gargery, a gentle giant of a man, a village blacksmith who works a forge adjoined to the family home. Pip’s miserable life in the parish is interrupted when his uncle, the pompous Mr. Pumblechook, is asked by the mysterious and wealthy Miss Havisham to locate a suitable young boy to spend time with her. The spinster Miss Havisham dwells in a decayed mansion that was “of old brick, and dismal, and had a great many iron bars to it. Some of the windows had been walled up; of those that remained, all the lower were rustily barred.” She lives with an equally mysterious young woman, the imperious and beautiful Estella. Miss Havisham, wearing a stained wedding gown, lives in suspended time, her clocks all stopped at twenty minutes to nine, the moment when, as a young woman, she was jilted by her lover:

I saw that the dress had been put upon the rounded figure of a young woman, and that the figure upon which it now hung loose, had shrunk to skin and bone. Once, I had been taken to see some ghastly waxwork at the Fair, representing I know not what impossible personage lying in state. Once, I had been taken to one of our old marsh churches to see a skeleton in the ashes of a rich dress, that had been dug out of a vault under the church pavement. Now, waxwork and skeleton seemed to have dark eyes that moved and looked at me. I should have cried out, if I could.

The room remains as it stood that day, eerily prepared for a wedding celebration that never took place: “It was spacious, and I dare say had once been handsome, but every discernible thing in it was covered with dust and mould, and dropping to pieces.” Pip continues to visit Miss Havisham in her ghostly chambers and receives payment for his company. In the course of his visits, he falls in love with Miss Havisham’s adopted daughter, Estella, who expresses no feeling at all for him in return. When Pip is inexplicably given a lavish allowance by an anonymous benefactor (he naturally suspects Miss Havisham), he moves to London to educate himself and become a gentleman, to fulfill the “great expectations” of the novel’s title.

From here, the stage is set for an examination of Pip’s development into manhood, through folly and humiliation, battling sensations of guilt while pursuing elusive love and struggling against enemies on the streets of London. Pip’s ambivalence and feelings of shame are something new in a Dickens novel, and they add to the already considerable intricacy of the work. Great Expectations is part coming-of-age story, part mystery, part morality tale, part love story, part thriller, though no one of these features ultimately defines it. Unlike most Dickens novels, Great Expectations challenges readers’ expectations. It does not present a battle between clearly defined forces of good and evil, and it refuses to serve up a triumphant ending in which noble figures are rewarded and villains sent off to die. In other words, it rather unsettlingly resembles real life.

Charles Dickens’s characters, so powerfully rooted in their times and places, are, at the same time, universal and timeless, by turns instructive, unsettling, comical, and enlightening. They offer useful lessons and are, in fact, nothing less than enduring meditations on humanity. They teach us a great deal about nineteenth-century England, its conflicts and concerns, its people and persuasions, but we are always surprised to find something of ourselves in his characters as well. Charles Dickens remains a favorite with both critics and readers, an unusual circumstance for a classic author. His fame survived his own era, while countless other authors, many of whom were celebrated and greatly admired in their day, have disappeared entirely from our shelves. The best Dickens novels stand shoulder to shoulder with the finest works of literature from any era. Perhaps no more proof of this is needed than the simple fact that we continue take pleasure in his works a century and a half after they first moved and delighted eager readers on the foggy streets of Queen Victoria’s London.

No Comments