Until now, I’ve only been able to share images taken on cell phones and smaller cameras, which you may have seen here. I’ve finally received some of the professional photographs taken by Scott Kimmins. Click on any image to enlarge. Enjoy!

Angela Mortellaro, who appeared with the Dayton Opera in the 2012 production of Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor, as Anna, in The Book Collector.

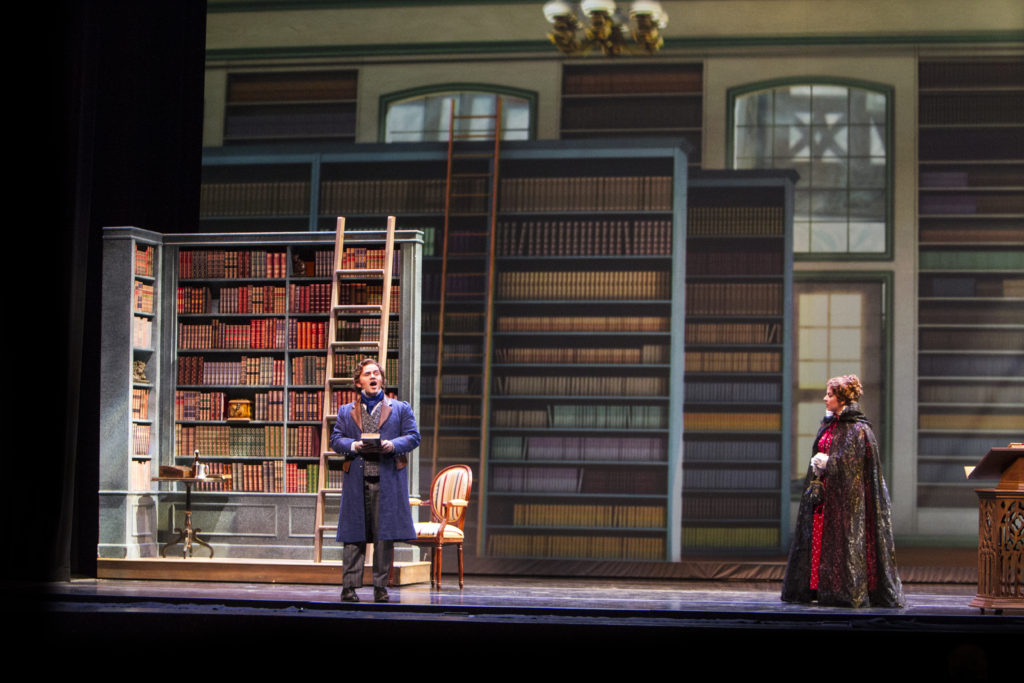

Tenor Andrew Owens as earnest and ambitious Bavarian book dealer Franz Bierman, in his shop on St. Martin Platz, where he and Anna bond over their shared loneliness and love of books.

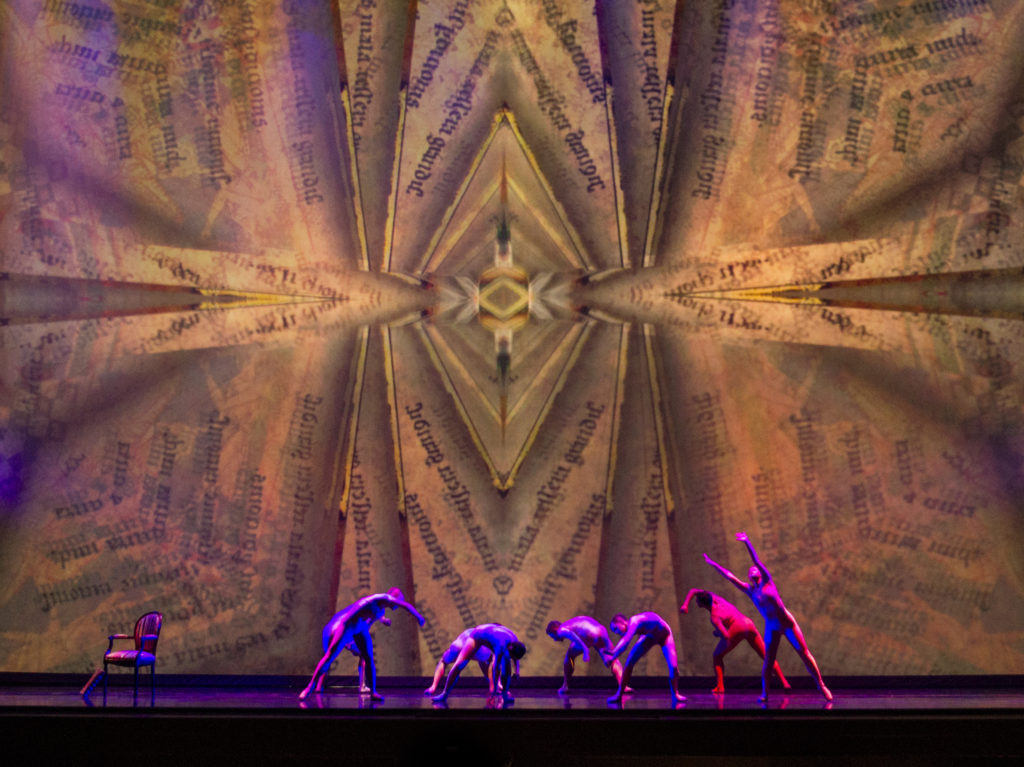

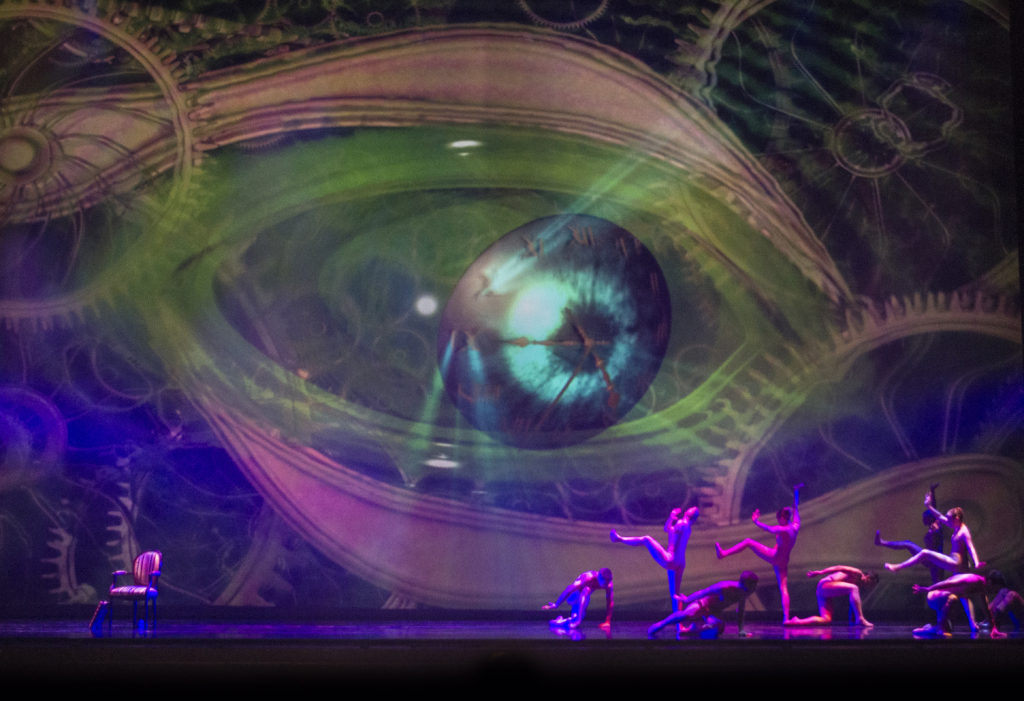

Bibliohallucinations accompany Franz Bierman’s near-death experience while reading his prized book. Choreography by Karen Russo Burke.

Baritone Andrew Garland as the compulsive, domineering book collector, Baron Otto von Schott, in the library of his ancestral fortress.

The split stage, displaying the baron’s oppressive library and Franz’s airy book shop emphasizes the divide we visualized between the Ancien Régime and the ascending mercantile class.

![The Baron sends his daughter, Anna, on a mission that could destroy them all. “Poison” Aria Just a little dust, Dark and red as rust, Just a little dust, Just enough to do what it must. Just enough to scare him. Enough to make him ill. Just enough to weaken him, But not enough to kill. So I may take back what he took. The very thing he stole. The one thing that can make me whole, The final, crucial book. I must complete what I’ve begun, Just one more shelf to fill. I must take back what he has won, I know, I must, I will. Just a little dust, Dark and red as rust, Just a little dust, Just enough to do what it must. [Baron laughs malevolently through clenched teeth]](http://www.everseradio.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/SK4L2657-1024x665.jpg)

The Baron sends his daughter, Anna, on a mission that could destroy them all.

“Poison” Aria

Just a little dust,

Dark and red as rust,

Just a little dust,

Just enough to do what it must.

Just enough to scare him.

Enough to make him ill.

Just enough to weaken him,

But not enough to kill.

So I may take back what he took.

The very thing he stole.

The one thing that can make me whole,

The final, crucial book.

I must complete what I’ve begun,

Just one more shelf to fill.

I must take back what he has won,

I know, I must, I will.

Just a little dust,

Dark and red as rust,

Just a little dust,

Just enough to do what it must.

[Baron laughs malevolently through clenched teeth]

Franz Bierman sings of the joy books have brought him over the years.

I am lost in their maps,

Stories, myths and facts,

Enchanted by their songs

Of noble deeds and wrongs,

Wicked husbands, clever wives,

I have lived all their lives.

Many soldiers, saints, and sages

I have seen in their pages.

Thanks to them, I have lived many lives.

In these books, I have lived many lives.

Franz Bierman’s paranoia gets the best of him. Who is watching him? Is the Baron trailing him? What of the silent monk who peers through his shop window before retreating into the crowded streets.

At the climax, the Baron, driven mad with desire for the book, commits murder! His daughter confronts him and is terrified when she realizes he does not understand what he has done and feels no remorse.

The enormity of his act becomes clear to the Baron, who has lost everything in his mad pursuit of the book he lost at auction.

The cathedral crumbles around the Baron as he struggles in the grip of madness . . .

Undone by desire that turned into madness,

I wanted all, too much, now left with none.

What I had thought was mine to possess,

My lot, remains forever unwon.

The world is upside down!

My second opera with composer Stella Sung, The Book Collector, premiered at the Dayton Opera on Friday, May 20th, 2016, with a matinee performance on Sunday May 22nd. The opera incorporated physical stage settings with virtual 3D digital backdrops, a ballet sequence, and full orchestra with choir.

Commissioned by Dayton Performing Arts Alliance in 2013 as a prologue to Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana, The Book Collector is a one-act Gothic tale of unforeseen fortunes and ancestral madness, young love and powerful obsession, played out against the backdrop of the Bavarian city of Bamberg—known across Europe as the “Franconian Rome” for its seven hills, each crowned with a beautiful church—at the start of the nineteenth century. The dashing and impulsive Baron Otto von Schott, long a recluse in his fortress, hopes to finally complete his collection of arcane books with the addition of a final mysterious volume, but he finds himself thwarted by Franz Bierman, a shrewd young bookseller. The enraged Baron plots revenge, ultimately entangling his lonely, unsuspecting daughter Anna in his deranged scheme to retrieve the book from the bookseller. Franz and Anna find themselves falling in love, and, after the unexpected intercession of a silent, enigmatic monk, the Baron’s madness deepens until it is finally too late for him to turn away from his own fate. This riveting new opera, combining traditional stagecraft with advanced 3D digital artwork, is not to be missed.

Music by STELLA SUNG

Libretto by ERNEST HILBERT

GARY BRIGGLE stage director

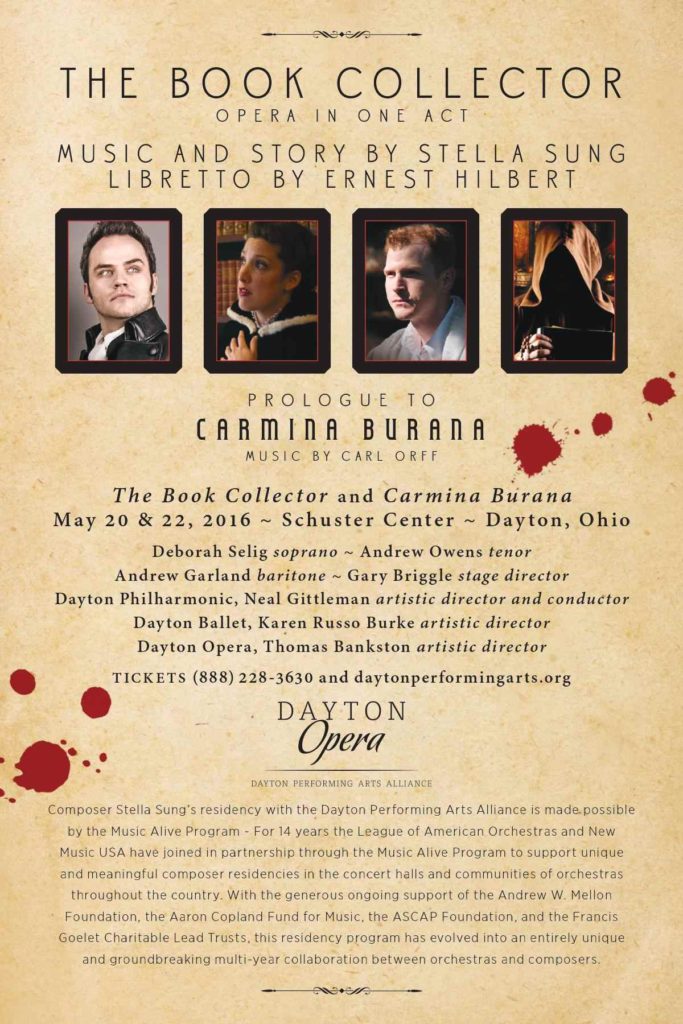

ANGELA MORTELLARO soprano – Anna von Schott

ANDREW OWENS tenor – Franz Bierman

ANDREW GARLAND baritone – Baron Otto von Schott

NEAL GITTLEMAN conductor

THOMAS BANKSTON opera artistic director

KAREN RUSSO BURKE choreographer

DAYTON PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA CHORUS

HANK DAHLMAN chorus director

DAYTON PHILHARMONIC

DAYTON OPERA

DAYTON BALLET

Synopsis

As the age of kings draws to an end at the turn of the nineteenth century, the Black Death pays a late visit to the Bavarian city of Bamberg, known across Europe as the “Franconian Rome” for its seven hills, each crowned with a beautiful church. The dashing and impulsive Baron Otto von Schott, long a recluse in his ancestral fortress, is led down the path of madness and obsession when he emerges to bid at auction for the final book he needs to complete his vast collection. To his astonishment, he is outbid by Franz Bierman, a respected local bookseller, and finds himself consumed with rage.

The indignant Baron, sensing a great injustice in being outbid by a commoner, plots revenge, ultimately entangling his lonely, unsuspecting daughter Anna in his deranged scheme to retrieve the book. The Baron dispatches Anna to Bierman’s shop on the St. Martin Platz, where she and Bierman bond over their shared loneliness and love of books. At her father’s insistence, she marks the pages of the coveted volume with a red dust, which he tells her will help him to find the book again one day but is actually intended to weaken Bierman with a mild poison that stimulates bizarre hallucinations. Anna, fearing her newfound feelings for Bierman and tormented by thoughts of her father, flees the shop after fulfilling her father’s wishes.

After leafing through the book, Franz, now poisoned, believes he is afflicted with the Black Plague and bargains with a silent monk, who has lurked at the edge of the scene, offering the monk the treasured book as alms to the church in return for a blessing. The monk departs with the book, never speaking. Anna, distraught, recognizes she is the last of a corrupt aristocratic line and wishes to flee her father’s growing madness. As an ominous summer storm looms, she enters St. Martinskirche to pray for their salvation. Bierman too seeks sanctuary in the church, but he is followed by the fanatical Baron, who demands the book, unaware it has already been spirited away and hidden by the monk. Anna watches helplessly as her father’s psychosis peaks in an unthinkable act.

Librettist’s Program Notes

In the spring of 2014, Stella Sung and I saw the production of our first collaboration, an opera called The Red Silk Thread: An Epic Tale of Marco Polo, a historical drama with elaborate settings, including the court of Kublai Khan, founder of the Yuan dynasty in 13th-century China, as well as the Khan’s imperial flagship at sea, the chaotic court of a corrupt Persian king, and even a Genoese prison, where Marco Polo writes his famous Travels. It was the first time in history that particular opera was seen and heard by an audience. After years of work, it rose wonderfully from a darkened stage to fill the hall with music and color and action, and, despite its length, it seemed to be over in no time at all. To be honest, now that I think back, I believe Stella may not have shared in my pleasure. A composer’s work is never done, and hers continued behind the scenes, but her work paid dividends. It is not often that a new opera comes to life, particularly in the 21st century. It is a something of a miracle when one does.

Later that same year, Stella approached me with an idea for a one-act opera that would serve as both prelude and companion piece to Carl Orff’s famous Carmina Burana, perhaps the most popular piece of 20th-century vocal music. This daunting new project was to be the culmination of her successful three-year tenure as the composer-in-residence at the Dayton Performing Arts League. Though we would be restricted to less than hour running time (relatively brief in the world of opera, where pieces in standard repertoire can easily run to three hours and more), we had honed several techniques in our time together that would serve us well as we began the new opera. We would observe more closely the classical unities of time, place, and action outlined by Aristotle in his Poetics. Rather than a large cast spanning continents and decades, as with our previous opera, the drama of The Book Collector would unfold in a single town, among three singers, over the course of a single day. This density placed considerable demands on the libretto from the start. Every word would have to count for a great deal.

We were familiar with the dramatic compressions necessary, on a practical level, to the production of an opera. Though it is an art form that has thrived on spectacle and expansiveness from its earliest days, there are always limits. For instance, though Kublai Khan may have had many hundreds of wives and consorts, I decided when writing the libretto for The Red Silk Thread to give lines only to his favorite three, whose names are known to history. A battle that may have raged for hours or days is resolved in a matter of minutes. A few dozen supernumeraries—generals, soldiers, ladies, guards, sailors, pirates—sufficed for our would-be cast of thousands. Likewise in The Book Collector, created a dramatic triad, the powerful Baron von Otto Schott, his forlorn daughter, Anna, and the gentle bookseller, Franz Bierman. We added non-singing roles to fill out the action, notably the auctioneer (who is heard but who does not sing) and the monk, who is entirely silent and serves as a Rorschach test when addressed by the other characters. At first, I planned to have the baron bid on a dozen quarto volumes at auction. These quickly shrank to become a single volume, which, for the sake of dramatic impact, was enlarged to an imperial folio with elaborate clasps and binding in order to register visually on stage.

Stella had a distinct vision for the opera from the first. The story is hers, and it was fully realized before she began work with me. My job, as librettist, was to broaden her story and deepen the characters by giving them the right words to sing. The baron’s impulsive nature would be brought to the fore through his curses and frenzied outbursts. His growing madness would be summoned by his fanatical repetition of certain phrases. Anna is innocent and inquisitive. This is reflected in her frequent use of the interrogative mood. Many of her lines are questions, far more than either of the other characters. She is in love with the world and wants to know more about it. Bierman’s fundamental decency and eagerness is displayed in his propensity to over-explain the simplest things in his efforts to please and impress the other characters. I was also compelled by thoughts of characters that were, by their very nature, absent. I saw the baron’s mania for filling his library as part of an emotional aftershock from the loss of his wife. In other words, though he assumes the role of villain in this opera, he was not always an angry, arrogant recluse. Her death also compels Anna to assume the role of the baron’s caretaker in her absence, thus trapping her in the home. Further, Bierman was not always driven by thoughts of profit and public advancement. In early drafts of the libretto, he too had lost someone he loved and, like the baron, looked for ways to fill the emptiness in his life.

I further sought to strengthen and emphasize the social and historical distinctions among the characters. The baron broods in his ancestral fortress, cluttered with the acquisitions of centuries, his library ill-lit, representative of a dark, aristocratic past of which he is the latest and perhaps last representative. Bierman exists in a world naturally lit by sunlight, his bookstore exceptionally ordered, a member of a rising middle class and part of an enlightened and more democratic age of commerce and shared knowledge. I took care to point out that the baron drinks wine, while Bierman, as his name would suggest, enjoys beer, a drink more common in the lower echelons of Teutonic society. The baron—born to inherited wealth he squanders and noble privilege that is quickly eroding—is in decline. Bierman is a commoner, but he rises. Anna is pulled between these two worlds, devastated by the weight of the first while daydreaming of escape into the second. What drives the baron? How has he focused his frustration in a world that no longer bows before him? He aims his emotional distress onto the acquisition of a book; not any book, but the single book he has convinced himself will complete his collection (though we sense that nothing could really fulfill this goal).

Stella and I decided that a method by which our new opera might tie itself to Orff’s Carmina Burana would be to imagine the baron questing after the final volume of the series of poems (also known as The Carmina Burana) on which Orff’s cantata is based. The extraordinary rarity and desirability of a single book is a very real thing. Consider Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies, the monumental 1623 volume commonly known as the First Folio, in which Shakespeare’s plays were collected for the first time seven years after his death, and including first appearances of many of the plays, such as Macbeth. Depending on condition and provenance, copies of the First Folio can achieve many millions of dollars on the rare occasion that one comes onto the auction block. Just last month, a copy was found forgotten on a shelf where it had lain for over a century in a house on the Scottish Isle of Bute. The discovery made news around the world.

The Carmina Burana (or Codex Buranas, literally the “Songs from Beuern,” the Bavarian district where the manuscripts were discovered), is a series of 254 poems written in Medieval Latin, Middle High German, and a few mongrel mixtures from the vernacular of several other languages. The poems include love songs, drinking and gaming ditties, moral and satirical poems, and religious dramas. Our notion of the baron having assembled many volumes of the poems and seeking to acquire the last is not far-fetched. Historically, it is quite possible that someone could have done so. Little is known of the origins or authorship of the Carmina, though it is likely that the manuscripts were written sometime in the early 13th century in Bavaria. The history of the manuscript after the middle of that century is murky. Scholar David Parlett suggests that “by the eighteenth century the manuscript must have presented a sadly dog-eared appearance, for it is then that it received its leather binding.” The tooling on the leather indicates that the binding was probably done at the monastery of Benedikbeuern.

What we do know is that after an 1803 decree secularizing ecclesiastical property in the region the volumes emerged from an uncatalogued library at the monastery, where they were kept away from other books in the official library, in what Parlett suggests may have been a type of index librorum prohibitorum of heretical writings. In other words, these volumes were not like the others the monks would have consulted or made available to outsiders. The monks may have chosen not to acknowledge the volumes’ existence for any number of reasons, perhaps simply because they did not know what they were. The first publication of the manuscripts would not come until 1847, when the collection was given its current title by its editor, Johann Andreas Schmeller, who had removed the volumes to Munich for cataloging. Just as Stella and I filled in the emotional spaces of the characters with words and music, we filled a historical gap by imagining the tortuous route by which the Carmina volumes came to rest in the monastery.

Although some of the poems are vaguely familiar to us today from Orff’s setting, he used only a small number of them. The original poems are still largely an enigma to American readers, though handfuls have been translated into English. I took the poems in the original Carmina Burana as models for the arias. The forms of the poems gave me license to write in verse, an artistic approach to the libretto that has fallen away since the nineteenth century and is now almost entirely extinct. For instance, using the ballad meter, or common measures, that appear in some of the Carmina poems (a remarkably durable accentual poetic form that can be still be heard today in lyrics sung by the likes of Katy Perry and Taylor Swift), I constructed similar stanzas to be sung by the baron, Bierman, and Anna. An example from the original Carmina Burana poems is CB 138:

In liehter varwe stat der walt,

der vogele schal nu donet,

div wunne ist worden manichvalt;

des meien tugende chronet . . .

Even if you can’t understand the language, you can detect its shape, the alternating rhythms of the lines, the clear rhymes. Just as Stella took inspiration from J. S. Bach, I deliberately echo this medieval stanza form in, for instance, the baron’s Mephistophelean “poison aria.”

I must complete what I’ve begun,

Just one more shelf to fill.

I must take back what he has won,

I know, I must, I will.

For the dénouement of The Book Collector, Stella and I decided to write a prologue to Orff’s Carmina Burana using Medieval Latin. The first stanza is borrowed from an anonymous 17th-century Catholic hymn for vespers and matins, “Quicumque certum quæritis,” translated as “All ye who seek a comfort sure” by Father Caswall, whose translation is the most commonly used. I composed the following two stanzas and worked closely with Christopher Childers, a classical scholar at Johns Hopkins University, to translate them into Medieval Latin from my original English.

I employed a combination of versecraft and traditional prose dialogue to propel Stella’s story, all the while posing and upending questions that vex characters across the history of literature and opera. How do the forces of fate and free will, circumstance and freedom, destiny and choice collide to create us? Where do our decisions lead, and how can we know they are entirely our own? What happens when we move headlong at all costs toward a goal we believe will make us happy? What do we lose by striving to remain independent? What do we risk when we place ourselves in the hands of another? These are the timeless themes Stella and I engage repeatedly in our work.

And so here we are, waiting for the curtain to go up after countless hours of composition and revision, construction and coding, preparations and rehearsals. Together, tonight, we will all witness a new opera for the first time, one that was forged with modern technology and artistic sensibilities to be part of an ancient tradition. We hope the stories and songs we conjure in the world of The Book Collector delight you and prove a memorable experience, even, perhaps—who knows?—one for the ages.