This is my introduction to a new, popular edition of four Jules Verne novels in translations by William Lackland, Frederick Amadeus Malleson, and Lewis Mercier, available in bookstores, online, and in big-box retail stores.

“VERNE FORESAW A WORLD OBSESSED WITH TECHNOLOGY, WHERE EVEN THOSE WHO CHOOSE TO AVOID IT CANNOT ESCAPE ITS INFLUENCE”

“VERNE FORESAW A WORLD OBSESSED WITH TECHNOLOGY, WHERE EVEN THOSE WHO CHOOSE TO AVOID IT CANNOT ESCAPE ITS INFLUENCE”

(ERNEST HILBERT) VERNE, Jules. Four Novels: Five Weeks in a Balloon, Journey to the Center of the Earth, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, Around the World in Eighty Days. San Diego: Baker and Taylor/Canterbury Classics, 2012. Stout octavo, hardcover. $16.95. ISBN-10: 1607103176.

Purchase from Amazon and Barnes and Noble.

* * *

LIFE

Jules Verne is one of the most famous authors of all time. He has been a best-seller for nearly a century and a half, in both his native French and many other languages, particularly English. According to UNESCO’s Index Translationum, only Agatha Christie is more frequently translated than Verne. Two of his most famous characters, the enigmatic Captain Nemo of Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea and the resolute Englishman Phileas Fogg of Around the World in Eighty Days, are commonly known to both children and adults the world over. Verne is celebrated as a pioneer of the science-fiction genre, a spinner of timeless adventure stories, and an endlessly readable chronicler of the last age of European exploration. He expressed the powerful and sometimes destructive Victorian faith in science as a means of surmounting obstacles and transforming the natural world. His stories endure today in movies, television, comics, cartoons, video games, and even amusement park rides.

Verne was born in 1828 in Nantes, France, a bustling harbor city on the Loire River near the Atlantic Ocean. Ships from around the world made fast at the wharves, and the air bristled with masts. As boys, Jules and his brother Paul explored the docks and riverbanks. From his earliest years, Jules watched vessels raise anchors for distant ports, and these departures sparked his imagination. At a young age, he developed an appetite for books about travel and exploration, and began writing for enjoyment. Poetry was “a family pastime” according to biographer Herbert R. Lottman, and Verne was attracted to literature from the start. His father was a successful attorney and hoped his son would follow him into the profession. When Verne moved to Paris to study law in 1848—a turbulent year of revolutions that began in Paris and spread across Europe—he quickly befriended other aspiring writers. With his friend Michel Carré he wrote opera libretti. He also composed poetry and plays and soon abandoned his law studies. His father was incensed and severed family support, but Verne continued to write while earning a living as a stockbroker, a profession he would practice until 1862. In 1857 he married Honorine de Viane Morel, a widow and mother of two. Unlike Verne’s father, she supported his writing and urged him to find a publisher. In time he met Pierre-Jules Hetzel, one of the most distinguished publishers of the age—and also one of the most demanding.

At age thirty-four, Verne sent the manuscript of his first novel, Five Weeks in a Balloon, to Hetzel. As critic Roger Cardinal explains, “Hetzel was delighted with Verne’s approach and at once offered him a long-term contract: the arrangement, involving a commitment to produce two books a year, was to last for the rest of the author’s life and established his financial security.” Thus began the Voyages Extraordinaires, or Extraordinary Voyages, the works for which Verne is best known. He would go on to write dozens of these novels and works of nonfiction, with more appearing after his death. The novelist Jane Smiley writes that Hetzel was “strong, almost dictatorial” as an editor, and he resisted any attempt on “Verne’s part to depict France, to have a less than happy ending,” or to “include any sort of sex or complex male-female relations.” Hetzel knew his audience, and he understood the bottom line. Lottman writes that “Hetzel would nurture Verne, making sure that his writing contained just the right mix of erudition and discovery.”

Hetzel’s domineering influence on Verne’s work may have inhibited the author in some regards, but as with any constraint placed on a great artist, it also enhanced his work in surprising ways. For instance, Verne originally conceived Captain Nemo as a Polish exile seeking revenge for the loss of his family in the Polish January Uprising against imperial Russia in 1863 (some of this hidden story remains, as when we see “the portrait of a woman, still young, and two little children . . . Nemo looked at them for some moments, stretched his arms toward them, and, kneeling down, burst into deep sobs”). Ever the businessman, Hetzel wanted to avoid ruffling political feathers and forced Verne to scour Nemo of nationality and motivation, which had the beneficial effect of transforming Nemo into an alluring enigma while adding a much-needed aura of inscrutability to the novel in which he appears. Although Hetzel “had a reputation as the publisher of serious writers like Balzac, Hugo, and Proudhon,” Cardinal insists that “it has to be acknowledged that Verne’s books were largely conceived as money-spinners targeting a wide popular audience.” Yet it is hardly to Verne’s detriment that he made money from his books, many of which have endured in a manner that few of the self-consciously literary novels of his time have not.

Verne’s life nicely matches that of the Victorian era of the late nineteenth century. The British established an empire that spanned North America, Australia, India, and Africa. The French colonial empire of the time—diminished from its height—included swathes of western Africa, Madagascar, and Southeast Asia. The industrial revolution spurred expansion of cities, brought about new technologies, and drove a golden age of invention. Verne lived to see the fantastic tales he pioneered taken up by others. H. Rider Haggard’s outlandish African epic King Solomon’s Mines appeared in 1885. The English author H. G. Wells (another contender to the title “father of science fiction”) arrived in 1895 with The Time Machine, followed by The Island of Dr. Moreau (1896), The Invisible Man (1897), The War of the Worlds (1898), and The First Men in the Moon (1901), though Verne felt Wells failed to ground his stories in established scientific fact. In 1912 Sir Arthur Conan Doyle published The Lost World, about a South American plateau where dinosaurs still reigned. H. P. Lovecraft mimicked Verne’s journeys to the poles in his terrifying scientific novella At the Mountains of Madness in 1931, long after the regions themselves had been explored.

Verne created a new type of character to populate his new type of novel. Cardinal labels his heroes “cerebral” adventurers. They are scholars, scientists, and cultured gentlemen, not soldiers, pirates, or knights. Still, they are heroic after the fashion of the time. Men like Verne and his characters—who deem conquest of the unknown to be among the highest virtues—belong to what the historian Oswald Spengler called “Faustian civilization,” endlessly and tragically striving for new frontiers. While these frontiers lasted, they piqued Verne’s curiosity. He was perfectly at home in the industrial age. He delightedly announced that the Victorian era was “witness to the most astonishing discoveries” and once declared, “I get as much pleasure out of watching a steam engine or a beautiful locomotive in motion as I do contemplating a painting by Raphael or Correggio.”

Jules Verne’s characters span the globe in search of knowledge, revenge, or merely to win a bet, but Verne himself never strayed far from France. He saw Italy and Scandinavia, Scotland, and other countries in Europe. He visited the north coast of Africa and made a brief trip to America on the SS Great Eastern, the largest ship ever built at the time; the ship inspired his 1871 novel A Floating City, and was used to lay the first lasting transatlantic telegraph cable. He toured New York City and made a short jaunt by rail to Niagara Falls. The globe-spanning journeys of the novels occurred only in his mind. It is a testament to his abilities, and to his everlasting credit, that they appear so credible to us even today.

* * *

SCIENCE FICTION OR FACT?

Translator and biographer William Butcher insists that “Verne is not a science-fiction writer: most of his books contain no innovative science. He did not write for children.” Smiley agrees, noting that “because his plots were exciting and exotic, he was pegged as a boy’s novelist,” though Verne “did not see his work as ‘science-fiction.’” This is true, to a point. Verne’s most famous “invention,” the submarine Nautilus, was inspired by early prototype submarines such as Robert Fulton’s 1800 Nautilus and the experimental Plongeur, exhibited at the 1867 Exposition Universelle. However, primitive submarines of one sort or another had been around for some time when Verne dreamed up the Nautilus. Nevertheless, it is hard to argue that Verne was not a science-fiction writer, even if the term itself usually refers to a later genre. It is true that much of the science Verne deployed was already commonly known, but it is rarely the main point, even if science—whether geography, oceanography, astronomy, or new applications in engineering, ballistics, and transportation—is essential to his method of storytelling. Smiley adds that “what Verne was always interested in was not exactly the goal (the center of the earth, for example) but the journey. He is writing in the tradition of Candide and even Don Quixote.” He wrote episodic adventures, a style as old as literature. His great innovation was the use of science and technology to move his stories forward and make them believable.

Verne was also at times a futurist. In 1863 he wrote Paris in the Twentieth Century, which Hetzel suppressed on the grounds that it was preposterous and not commercially viable. The novel was not published until 1994, 131 years after it was written. Verne envisioned Paris in 1960 packed with skyscrapers (perhaps not Paris, but many cities would spawn such prodigious skylines), where society is dominated by the demands of business and technology. In his 1865 novel From the Earth to the Moon and its 1870 sequel Around the Moon, Verne launches his heroes in a capsule from Florida. They visit the moon and eventually splash down in the ocean to be picked up by a U.S. Navy vessel. This prefigures NASA’s Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo missions in the 1960s with one significant difference: Verne’s characters are shot out of a giant gun. Novelists are not prophets; they are storytellers. Verne used science to excite readers. His love of technical detail, awareness of contemporary scientific theories, and trust in scientific advancement saturate his books, as one finds when the imperturbable Professor Liedenbrock of A Journey to the Center of the Earth proclaims: “When science has uttered her voice, let babblers hold their peace.” It is worth noting, however, that later in life Verne took a grimmer view of scientific progress in novels like Robur the Conqueror (1886) and its sequel Master of the World (1904).

Verne’s fame and wealth grew throughout his life. He earned considerable income from stage adaptations of his novels. He purchased a yacht, the Saint-Michel, which he would upgrade with the larger Saint-Michel II and even larger Saint-Michel III. He enjoyed leisurely cruises, during which he would take copious notes for his works. Most of his life is believed to have been spent in productive domestic tranquility. Sadly, in 1886 events turned against Verne. His deranged twenty-five-year-old nephew Gaston shot him in the leg; Gaston was dispatched to an asylum for the remainder of his life while the family tried to keep the affair quiet. The following year, both his mother Sophie and publisher Hetzel died. Verne turned to local politics in Amiens, where he lived the remainder of his life, and served admirably as town councilor for fifteen years, even as he continued to write and publish. He died at home in 1905.

* * *

FIVE WEEKS IN A BALLOON

Jules Verne’s first novel, Five Weeks in a Balloon, was published in 1863 as Cinq semaines en balloon and translated into English for the first time six years later. Edgar Allan Poe’s stories “The Balloon Hoax” and “The Unparalleled Adventures of One Hans Pfaal,” translated in 1856 by the poet Charles Baudelaire, may have served as inspiration for Five Weeks in a Balloon, but nothing prepared readers for Verne’s maiden Extraordinary Voyage. It is the first novel of its kind, joining exhilarating adventure with persuasive (though speculative) scientific theory. Lottman believes Verne wrote “the ‘new kind of novel,’ a book so different from anything he or anyone else had done or tried to do until then, it seems an amazing achievement.” It was an overnight success and was adapted into a long-running play in Paris, celebrated for its extravagant sets and the use of a live elephant. Of his many novels, only Around the World in Eighty Days would sell more copies.

As with many of Verne’s works, the heroes of Five Weeks in a Balloon start out in rather tame surroundings—the Royal Geographical Society of London—only to journey into what were then considered wild, uncivilized regions. Dr. Ferguson, a scientific genius and intrepid explorer, recruits his “easy, logical, [and] natural” manservant Joe and the “open, resolute, and headstrong” (but reluctant) Scottish sportsman Kennedy for a bold attempt to traverse Africa—then only partly explored and barely understood by Europeans—by balloon from the island of Zanzibar on the east coast to the French territories on the Atlantic Ocean in the west. For this purpose, Ferguson invents a device that allows his balloon—the Victoria, named after Britain’s queen—to easily change altitude without relieving the craft of ballast or increasing the amount of gas. Like Verne, Ferguson sees progress as inevitable, or, as he puts it, “because, what cannot be done in one way, should be tried in another.”

As with many of Verne’s works, the heroes of Five Weeks in a Balloon start out in rather tame surroundings—the Royal Geographical Society of London—only to journey into what were then considered wild, uncivilized regions. Dr. Ferguson, a scientific genius and intrepid explorer, recruits his “easy, logical, [and] natural” manservant Joe and the “open, resolute, and headstrong” (but reluctant) Scottish sportsman Kennedy for a bold attempt to traverse Africa—then only partly explored and barely understood by Europeans—by balloon from the island of Zanzibar on the east coast to the French territories on the Atlantic Ocean in the west. For this purpose, Ferguson invents a device that allows his balloon—the Victoria, named after Britain’s queen—to easily change altitude without relieving the craft of ballast or increasing the amount of gas. Like Verne, Ferguson sees progress as inevitable, or, as he puts it, “because, what cannot be done in one way, should be tried in another.”

Ferguson is a man of fate. “He claimed that he was impelled, rather than drawn by his own volition, to journey as he did,” like a “locomotive, which does not direct itself, but is guided and directed by the track it runs on.” His motto “Excelsior!” (meaning “ever higher”) captures the sense of unbridled progress that marked the thinking of the age. The principal goal of his expedition is to link the voyages of Sir Richard Burton and John Hanning Speke in East Africa with those of the German explorer Heinrich Barth in the Sahara in order to locate the fabled and long-sought source of the Nile River, which had thus far eluded explorers, many of whom died trying to find it. Readers would have known that a trip across Africa in a balloon could hardly be accomplished without some danger. In fact, Verne provides an African martyrology, a gruesome catalog of explorers who died of thirst, disease, or at the hands of native African populations, who were understandably less than pleased with European incursions.

The tribes inhabiting the region seemed excited and hostile; they manifested more anger than adoration, and evidently saw in the aeronauts only obtrusive strangers, and not condescending deities. It appeared as though, in approaching the sources of the Nile, these men came to rob them of something.

During their journey Ferguson and crew cross over the great lakes of Africa (including Lake Victoria), treacherous mountain peaks, and the legendary ancient city of Timbuktu. Because so much of the journey takes place over then-unmapped territory, Verne was obliged to invent landscapes. He incorrectly compares the lush grassland of the savanna to the surface of the moon. Verne may be forgiven this, as the book is, after all, a work of imaginative literature, speculating about worlds unknown.

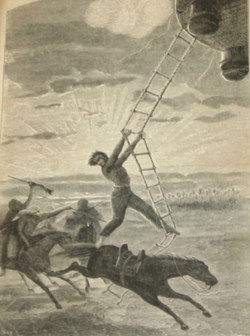

Along the way, the trio finds itself ensnared in a variety of perilous situations, as when their anchor inadvertently hooks a bull elephant in high grass, or when they descend to liberate a missionary about to be ritually sacrificed by a cannibal tribe. They are harassed by squadrons of giant condors and find themselves drifting listlessly, like the Ancient Mariner, without wind or water over an endless wasteland. Five Weeks in a Balloon contains action scenes worthy of a blockbuster Hollywood film, as when Joe, pursued on horseback by a regiment of enraged and heavily armed Arab horsemen, leaps in the nick of time from his exhausted horse directly onto a rope ladder dangling from the balloon.

Joe clung with all his strength to the ladder during the wide oscillations that it had to describe, and then making an indescribable gesture to the Arabs, and climbing with the agility of a monkey, he sprang up to his companions, who received him with open arms.

Amusingly, the novel anticipates news of the actual discovery of the source of the Nile. In fact, Speke’s book Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile appeared only a few months after the fictional Ferguson is credited with the feat.

Five Weeks in a Balloon is an astounding first novel, but it is not without defects. Verne’s labored descriptions of the balloon sometimes slows the novel’s pace, and his depictions of native African cultures—of which he would have known little or nothing—may seem coarse and even, at times, repugnant to modern sensibilities. Nonetheless, Verne forged a lasting story of perseverance that changed expectations of what a novel could achieve. After several false starts, he had also begun on one of the most spectacular and successful literary careers of all time.

* * *

A JOURNEY TO THE CENTER OF THE EARTH

Journey to the Center of the Earth, the third Extraordinary Voyage, was published by Hetzel in 1864 as Voyage au centre de la Terre, appearing in English translation in 1871. Brian Taves and Jean-Michel Margot describe it as “one of Verne’s most enduring and mythically powerful works.” Indeed, the novel displays affinities with ancient stories about travel to the underworld, such as Homer’s Odyssey, Virgil’s Aeneid, the myths of Persephone and Orpheus, and, later, Dante’s Inferno, though in Verne’s vision the underworld has been scrubbed, for the most part, of any specific mythical and religious significance. Rather, it is perceived geologically by Professor Liedenbrock, a German who hopes to be the first to publish a book on the subject. Hollow-earth theories are as old as human civilization and persist to this day. Verne would have known of prominent advocates such as the Scottish physicist Sir John Leslie, who suggested that two suns resided at the earth’s core. Another, the American John Cleves Symmes Jr., believed the earth consisted of several concentric shells with openings at each pole. Although modern science has completely disproven such notions, it hardly detracts from the wonderful tension Verne crafts as Liedenbrock and his skeptical nephew Axel (who tells the story) penetrate ever deeper into the earth’s core and discover all manner of peculiar and seemingly impossible phenomena.

Journey to the Center of the Earth, the third Extraordinary Voyage, was published by Hetzel in 1864 as Voyage au centre de la Terre, appearing in English translation in 1871. Brian Taves and Jean-Michel Margot describe it as “one of Verne’s most enduring and mythically powerful works.” Indeed, the novel displays affinities with ancient stories about travel to the underworld, such as Homer’s Odyssey, Virgil’s Aeneid, the myths of Persephone and Orpheus, and, later, Dante’s Inferno, though in Verne’s vision the underworld has been scrubbed, for the most part, of any specific mythical and religious significance. Rather, it is perceived geologically by Professor Liedenbrock, a German who hopes to be the first to publish a book on the subject. Hollow-earth theories are as old as human civilization and persist to this day. Verne would have known of prominent advocates such as the Scottish physicist Sir John Leslie, who suggested that two suns resided at the earth’s core. Another, the American John Cleves Symmes Jr., believed the earth consisted of several concentric shells with openings at each pole. Although modern science has completely disproven such notions, it hardly detracts from the wonderful tension Verne crafts as Liedenbrock and his skeptical nephew Axel (who tells the story) penetrate ever deeper into the earth’s core and discover all manner of peculiar and seemingly impossible phenomena.

The story begins when Professor Liedenbrock happens upon a runic cryptogram concealed in an antiquarian volume of the poet of Snorre Turlleson’s Icelandic saga Heims Kringla. After translating the runes into Latin letters, he is driven nearly mad in his efforts to decode the apparently meaningless words. Axel begins to worry for his uncle’s health.

When I awoke next morning that indefatigable worker was still at his post. His red eyes, his pale complexion, his hair tangled between his feverish fingers, the red spots on his cheeks, revealed his desperate struggle with impossibilities, and the weariness of spirit, the mental wrestlings he must have undergone all through that unhappy night.

Out of desperation Liedenbrock locks the house, with Axel and their maid Martha inside, until he can crack the code, but he meets with no success. In the first of several comic flourishes, young Axel discovers, while casually fanning himself with the parchment before a bright fire, that the bizarre characters reveal themselves as rough Latin sentences when viewed from the back. Read in reverse, they tell of a passage into the earth’s center.

Descend, bold traveler, into the crater of the jokul of Sneffels, which the shadow of Scartaris touches before the kalends of July, and you will attain the center of the earth; which I have done, Arne Saknussemm.

Liedenbrock is determined to retrace Saknussemm’s steps, against all known scientific learning and common sense. Axel fears the message is a hoax, but he is enlisted by his unshakably confident uncle. As the ominous journey looms, Verne keeps his sense of humor, as when Martha inquires in a concerned way about the trip:

“Is master mad?” she asked.

I nodded my head.

“And is he going to take you with him?”

I nodded again.

“Where to?”

I pointed with my finger downward.

“Down into the cellar?” cried the old servant.

“No,” I said. “Lower down than that.”

Liedenbrock and Axel set out for Iceland, where they acquire a guide, Hans Bjelke, a “grave, phlegmatic, and silent individual” who leads them to the extinct volcano Sneffels. At the end of June, the shadow of the neighboring peak Scartaris points to the cave entrance. As they descend ever further they nearly expire of thirst before Hans locates a subterranean river and breaks through to it (it is boiling hot). At last, they emerge into an impossibly vast cavern that cradles an underground sea, with a ceiling so high that it contains clouds, all bathed in an eerie light supplied by electrically charged gas.

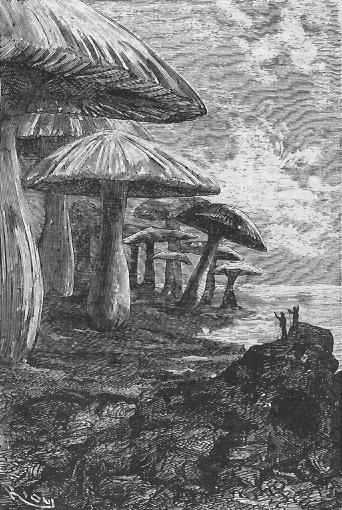

Liedenbrock indulges the European explorer’s penchant for baptizing new discoveries (the boiling river is named the “Hansbach” in honor of Hans; he claims the sea as “Liedenbrock Sea” and later a small geyser island for Axel). They stroll beneath tree-sized mushrooms as Hans fashions a raft from petrified trees, then set sail on the Liedenbrock Sea, which they suspect may be “as wide as the Mediterranean.” They witness a terrifying battle between an ichthyosaurus and a plesiosaurus, two colossal marine reptiles believed long extinct:

Those huge creatures attacked each other with the greatest animosity. They heaved around them liquid mountains, which rolled even to our raft and rocked it perilously. Twenty times we were near capsizing.

Later, they drift helplessly into a titanic and terrifying storm:

The most vivid flashes of lightning are mingled with the violent crash of continuous thunder. Ceaseless fiery arrows dart in and out among the flying thunderclouds; the vaporous mass soon glows with incandescent heat; hailstones rattle fiercely down, and as they dash upon our iron tools they too emit gleams and flashes of lurid light. The heaving waves resemble fiery volcanic hills, each belching forth its own interior flames, and every crest is plumed with dancing fire.

Verne is never more prone to fabulous contrivances than in A Journey to the Center of the Earth. In one chapter, Axel glimpses a colossal primitive man who shepherds woolly mammoths, a figure reminiscent of the Cyclops from the Odyssey. This is a rare example of Verne describing something that is simply not scientifically possible even by the standards of his own age. However, as Lottman points out, Verne includes an escape clause: “When Axel later recalls the discovery—for it is he who writes the log of their odyssey—he wonders whether they really saw this twelve-foot-tall superhuman specimen.”

Like Odysseus and his crew, the three finally arrive back at the earth’s surface, near Sicily, a great distance from the frozen volcano they entered.

There were those who envied [Liedenbrock] his fame; and as his theories, resting upon known facts, were in opposition to the systems of science upon the question of the central fire, he sustained with his pen and by his voice remarkable discussions with the learned of every country.

Having trekked through the very bowels of the earth, meeting terrible monsters and suffering unthinkable deprivations, the professor is met with his just reward of scholarly recognition—a truly Vernian ending.

* * *

TWENTY THOUSAND LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea was first published in 1870 as Vingt mille lieues sous les mers, the sixth of Verne’s Extraordinary Voyages. William Butcher recognizes it as “Verne’s most ambitious novel in terms of the breadth and diversity of its themes and psychology.” Indeed, it deserves to be considered his masterpiece, the novel with which he is most closely associated and which continues to exert the strongest pull on the popular imagination. It is more sweeping, lyrical, and elegiac than his other novels. It is where his imagination grows truly oceanic. Verne himself admitted, “I’ve never held a better thing in my hands.” Part of his chronicle may have been shaped by Victor Hugo’s 1866 novel Toilers of the Sea, which contains a battle with a massive octopus. It also exhibits certain kinships with Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick (1851), a maritime epic whose principal character, Ahab, is, like Nemo, driven by madness toward his doom (both Moby-Dick and Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea end with enormous whirlpools).

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea was first published in 1870 as Vingt mille lieues sous les mers, the sixth of Verne’s Extraordinary Voyages. William Butcher recognizes it as “Verne’s most ambitious novel in terms of the breadth and diversity of its themes and psychology.” Indeed, it deserves to be considered his masterpiece, the novel with which he is most closely associated and which continues to exert the strongest pull on the popular imagination. It is more sweeping, lyrical, and elegiac than his other novels. It is where his imagination grows truly oceanic. Verne himself admitted, “I’ve never held a better thing in my hands.” Part of his chronicle may have been shaped by Victor Hugo’s 1866 novel Toilers of the Sea, which contains a battle with a massive octopus. It also exhibits certain kinships with Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick (1851), a maritime epic whose principal character, Ahab, is, like Nemo, driven by madness toward his doom (both Moby-Dick and Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea end with enormous whirlpools).

The novel begins with worldwide hysteria triggered by an “extraordinary creature” that defies all scientific explanation. “For some time past vessels had been met by ‘an enormous thing,’ a long object, spindle-shaped, occasionally phosphorescent, and infinitely larger and more rapid in its movements than a whale.” The mythical depths of Verne’s darkest novel are present from the start.

In every place of great resort the monster was the fashion. They sang of it in the cafés, ridiculed it in the papers, and represented it on the stage. All kinds of stories were circulated regarding it. There appeared in the papers caricatures of every gigantic and imaginary creature, from the white whale, the terrible “Moby Dick” of sub-arctic regions, to the immense kraken, whose tentacles could entangle a ship of five hundred tons and hurry it into the abyss of the ocean. The legends of ancient times were even revived.

Dr. Arronax, a French marine scientist and author of Mysteries of the Great Submarine Grounds, is invited to join the crew of the American steam frigate Abraham Lincoln, a warship “of great speed” commissioned by the U.S. government to hunt down and destroy the monster. Unable to resist an opportunity to add to his store of aquatic knowledge, Arronax accepts the offer and brings his servant Conseil, who possesses a Linnaean ability to place animals according to zoological classification. Onboard, they meet Ned Land, a robust, broad-shouldered Canadian, “prince of harpooners,” who is determined to add to his impressive tally of kills.

When the Abraham Lincoln finally confronts the monster, Ned Land hurls a harpoon that bounces from its side. Arronax recounts “a fearful shock followed, and, thrown over the rail without having time to stop myself, I fell into the sea.” Land is also knocked overboard, while Conseil, ever loyal, dives after his master. As the stricken frigate drifts away, the three find themselves clinging for life to the metal shell of a submarine. They are soon taken captive by its crew (which speaks an unknown language) and meet the mysterious Captain Nemo, who agrees to allow them aboard his submarine, the Nautilus, as captive guests.

They proceed to travel around the globe—the 20,000 leagues of the title, which equals about 50,000 miles—astounded both by real and mythical wonders (it is actually helpful to have an atlas or globe handy while reading the book, in order to trace the progress of the Nautilus). Nemo’s submarine is more of a gentleman’s ancestral manor than a machine-age vessel, distinguished by what the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction describes as “Second Empire plushness . . . ornate luxury enabled by advanced technology.” Unlike real submarines, the Nautilus is quite roomy, appointed with a library, parlors, and Nemo’s pipe organ. Arronax describes Nemo’s private museum:

A luminous ceiling, decorated with light arabesques, shed a soft clear light over all the marvels accumulated in this museum. For it was in fact a museum, in which an intelligent and prodigal hand had gathered all the treasures of nature and art, with the artistic confusion which distinguishes a painter’s studio.

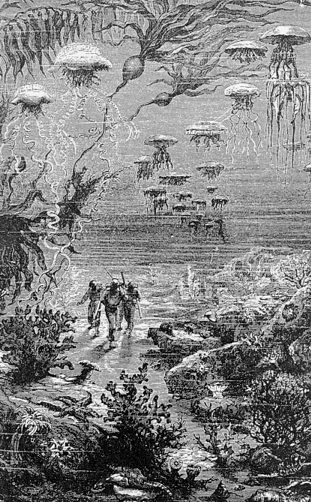

Arronax is drawn to the research possibilities of the Nautilus and begins to feel comfortable in its shell, like a snail, even as Ned Land doggedly pursues any possible avenue of escape. Together with Conseil, they attend undersea hunting excursions, reconnoiter sunken wrecks, cower as the Nautilus is boarded by curious cannibals, observe a solemn undersea burial in a coral grove, harvest coconut-sized pearls from giant clams, clash with sharks, visit the lost city of Atlantis (perched on the edge of an active underwater volcano that lights it in the darkness), attain the South Pole (Nemo plants a black flag emblazoned with an “N” more than forty years before the Norwegian Roald Amundsen actually set foot there), find themselves trapped inside a capsized iceberg (one of the novel’s most powerful scenes), and battle gigantic squids.

Nemo, whose name means “no man” in Latin, is moody, prone to disappear for days at a time, his motives never properly understood by his guests.

“Professor,” replied the commander, quickly, “I am not what you call a civilized man! I have done with society entirely, for reasons which I alone have the right of appreciating. I do not, therefore, obey its laws, and I desire you never to allude to them before me again!”

When Arronax, Conseil, and Land are forced into their cabin and drugged, they realize that the Nautilus is being used not only for scientific good but also for violence: “Captain Nemo was not satisfied with shunning man. His formidable apparatus not only suited his instinct of freedom, but perhaps also the design of some terrible retaliation.” Nemo’s hatred of the surface world is matched by a devotion to the sea, as he expounds in one of the novel’s finest passages.

“Yes; I love it! The sea is everything. It covers seven tenths of the terrestrial globe. Its breath is pure and healthy . . . The sea is only the embodiment of a supernatural and wonderful existence. It is nothing but love and emotion; it is the ‘Living Infinite,’ as one of your poets has said . . . In it is supreme tranquility. The sea does not belong to despots. Upon its surface men can still exercise unjust laws, fight, tear one another to pieces, and be carried away with terrestrial horrors. But at thirty feet below its level, their reign ceases, their influence is quenched, and their power disappears.”

We see the story through Aronnax’s eyes, but it is quite possible that Verne saw something of himself in Nemo. Lottman suggests that “amateur psychologists would have a field day comparing the curiously withdrawn Jules Verne, who would become increasingly solitary, with this submarine captain, whose eccentricity the author had yet to explain.” Verne’s grandson Jean Jules-Verne once remarked that the author’s three loves were “freedom, music, and the sea.” Indeed, Nemo dedicates himself to the sea, cherishes his independence (his motto is “Mobilis in mobili,” which can be translated from the Latin as “mobile in the mobile element”), and enjoys thundering away on his private pipe organ (he plays only the black keys, which gives his music a dark resonance).

The ocean world is at times placid, as when Conseil itemizes schools of flamboyantly colored fish through the observation window, and at other times downright terrifying. One of the book’s most famous scenes is the attack of the giant squids, referred to as “poulps” in the present translation (poulp means “octopus” in French, but what Verne describes are squid). They are terrifyingly large and manage to carry off a crewmember; Verne may have been inspired by naturalist Pierre Denys de Montfort, who was fascinated by the idea of giant octopuses and claimed that some had pulled down whole ships.

Before my eyes was a horrible monster worthy to figure in the legends of the marvelous. It was an immense cuttlefish, being eight yards long. It swam crossways in the direction of the Nautilus with great speed, watching us with its enormous staring green eyes. Its eight arms, or rather feet, fixed to its head, that have given the name of cephalopod to these animals, were twice as long as its body, and were twisted like the furies’ hair.

At the novel’s climax, the Nautilus is attacked by a warship that flies no national flag. When urged by Arronax not to sink it, Nemo’s lashes out.

“I am the law, and I am the judge! I am the oppressed, and there is the oppressor! Through him I have lost all that I loved, cherished, and venerated—country, wife, children, father, and mother. I saw all perish! All that I hate is there! Say no more!”

Nemo identifies with the downtrodden and seeks to help them. In the course of the novel he gives a bag of pearls to an exploited Ceylonese diver and later delivers a cache of gold, recovered from sunken ships, to Greeks, presumably to fund their uprising against Ottoman rule in the 1866–69 Cretan Revolt. As the emotional depth of Nemo’s character is revealed, Arronax begins to see him in heroic and even mythical terms.

Then Captain Nemo seemed to grow enormously, his features to assume superhuman proportions. He was no longer my equal, but a man of the waters, the genie of the sea.

At the novel’s end, the Nautilus is dragged into a huge whirlpool off the coast of Norway, just after Arronax, Conseil, and Land finally manage to escape. The mysteries of Nemo’s past, his motives, and the bizarre language used by his crew remain unexplained. Arronax muses on Nemo and wonders, almost hopefully, if he survived.

But what has become of the Nautilus? Did it resist the pressure of the maelstrom? Does Captain Nemo still live? And does he still follow under the ocean those frightful retaliations? . . . Will the waves one day carry to him this manuscript containing the history of his life?

Nemo lives on as one of the most famous—and infamous—characters of the nineteenth century (he also appears in Verne’s 1874 sequel, The Mysterious Island). He still intrigues us. We are disgusted by his violence yet charmed by his intelligence and moved by his sympathy for the oppressed. Like Arronax, we find ourselves forever lured back onto the Nautilus.

* * *

AROUND THE WORLD IN EIGHTY DAYS

Verne’s eleventh Extraordinary Voyage is Around the World in Eighty Days, published in 1873 as Le tour dumonde en quatre-vingts jour. Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea may be Verne’s masterpiece, but Around the World in Eighty Days remains his most popular. A comic novel inhabited by memorable characters, it speeds along at breakneck pace. It is the novel that sold best during Verne’s lifetime. In fact, it was a sensation. Many readers believed that the journey was actually taking place as they read newspaper excerpts that preceded book publication. The final excerpt was cunningly scheduled to appear on December 22, 1872, the day the story ends. By the 1870s, Verne’s heroes had journeyed to the moon and the seafloor, the icy poles and across Africa. There seemed to be no place left to map. The age of exploration had given way to the age of tourism. Instead of legendary discoveries, Verne is forced to convey the frantic and lonely pace of the modern world. As Butcher points out, “under its gay abandon . . . Around the World in Eighty Days is streaked with the melancholy of transitoriness.”

Verne’s eleventh Extraordinary Voyage is Around the World in Eighty Days, published in 1873 as Le tour dumonde en quatre-vingts jour. Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea may be Verne’s masterpiece, but Around the World in Eighty Days remains his most popular. A comic novel inhabited by memorable characters, it speeds along at breakneck pace. It is the novel that sold best during Verne’s lifetime. In fact, it was a sensation. Many readers believed that the journey was actually taking place as they read newspaper excerpts that preceded book publication. The final excerpt was cunningly scheduled to appear on December 22, 1872, the day the story ends. By the 1870s, Verne’s heroes had journeyed to the moon and the seafloor, the icy poles and across Africa. There seemed to be no place left to map. The age of exploration had given way to the age of tourism. Instead of legendary discoveries, Verne is forced to convey the frantic and lonely pace of the modern world. As Butcher points out, “under its gay abandon . . . Around the World in Eighty Days is streaked with the melancholy of transitoriness.”

The novel’s hero, Phileas Fogg, is as inflexible and secretive as Nemo in his own way. He is a proper English gentleman who never deviates from his precise daily routine, which takes him from his home in Saville Row to the Reform Club, where he spends the day reading newspapers and playing whist, and then back home again. Nothing is known about him or how he acquired his fortune. “Phileas Fogg was a member of the Reform, and that was all.”

Was Phileas Fogg rich? Undoubtedly. But those who knew him best could not imagine how he had made his fortune, and Mr. Fogg was the last person to whom to apply for the information. He was not lavish, nor, on the contrary, avaricious . . . He was, in short, the least communicative of men.

His life is so exacting that he dismisses his servant “because that luckless youth had brought him shaving-water at eighty-four degrees Fahrenheit instead of eighty-six.” The hapless valet is replaced by Passepartout, a Frenchman of many trades, including gymnastics instructor. He is “well-built, his body muscular, and his physical powers fully developed by the exercises of his younger days.” He hopes to settle down to a quiet life as a gentleman’s gentleman in London.

While playing whist, his only known pastime, Fogg finds himself embroiled in a debate about a recent bank robbery. A “gentleman of polished manners, and with a well-to-do air” has made off with a great deal of money from the Bank of England. While a banker insists that the robber will be easily apprehended, others are less certain. They suggest that the world has “grown smaller” and that, consequently, a robber could avoid capture by moving to the far side of the globe very quickly. Fogg agrees and wagers that he can travel around the world in exactly eighty days. To the astonishment of his fellow clubmen, who accept his challenge, he dashes off straightaway. Passepartout, who “mechanically set about making the preparations for departure,” wonders if his master is a fool, or if it is all an elaborate joke.

The wager may seem a frivolous reason to travel around the world, but it is more than a gimmick. It is important for two reasons. First, Fogg is an emblem of humdrum English life, a middle-aged bachelor without purpose. He seeks any justification to break out of his routine before it is too late to do so. Second, the world was, in a sense, shrinking in the Victorian era due to several developments: telegraph cables (news of Fogg’s progress excites gamblers across England), canals (the Suez Canal opened in 1869), steamships, and railways such as the Great Indian Peninsula Railway and the American transcontinental railroad. Fogg, “calm and phlegmatic, with a clear eye” and “English composure” seems utterly isolated from his surroundings as he travels. Foreign cultures may not serve as impediments to his progress, but they do not have an appreciable effect on him either. In other words, he remains unmoved as he moves, a living symbol of British fortitude.

By the time Fogg reaches Suez, he is shadowed by a bumbling and persistently frustrated detective named Fix, who is convinced that Fogg is the gentlemanly bank robber. Unfortunately for Fix, he must adhere to the British rule of law in the empire’s dominions, and the arrest warrants he requests from London invariably appear too late in each stage of the journey to be of any use. Delays and cancelations threaten Fogg’s timetable, but at each setback he calmly proceeds by another method. The first major setback occurs when he learns that the train from Bombay (Mumbai) to Calcutta has not actually been completed as reported in the newspapers. Passengers are invited to disembark and walk fifty miles to the nearest railhead. Faced with a looming deadline, Fogg acquires an elephant and starts off again through the jungle. With the help of a British officer, Sir Francis Cromarty, who is on his way to rejoin a garrison at Benares, they rescue a young Indian woman, Aouda, about to be burned on the funeral pyre of her husband. Following a daring escape from the infuriated congregation, Fogg, Passepartout, and Aouda continue to make their way across Asia and America, moving steadily from one mishap to another, with the ever-determined Fix in tow.

Around the World in Eighty Days is defined by tensions between the ideal and the real. It shows how best-laid plans go astray. It is quite an achievement to conjure so much animated adventure from steamship timetables and railway delays, but it works splendidly. It is a sketch of the British Empire at its peak, envisioned by a Frenchman who never saw the regions himself. (Gonzague Saint Bris declares, “Jules Verne is the great bard of Victorian England.”) Additionally, Around the World in Eighty Days allows Verne to venture one last great prediction. He saw an age in which tourists would dash from place to place, hardly absorbing their surroundings, before returning home again.

* * *

LEGACY

Jules Verne is one of those rare authors whose creations have long outlived their creator. His stories have entered our minds from many directions. Even those who have never read his books will recognize the name Nemo. Verne foresaw a world obsessed with technology, where even those who choose to avoid it cannot escape its influence. John Derbyshire comments that “perhaps a better title for Verne is ‘Father of Tech-Fi,’ of stories that revolve around the fanciful possibilities of technology to harness nature’s powers, to aid human adventure, and to rescue men from terrible perils.” Some suggest that Verne profoundly changed the very ways in which we think. In a 1975 address to the U.S. Congress, the famed science-fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke observed that “we would not have had men on the moon if it had not been for Wells and Verne and the people who write about this and made people think about it.”

On the occasion of a 2006 Smithsonian Institution Libraries exhibit dedicated to Verne, Norman Wolcott wrote that Verne was the first “to recognize that the new world of nineteenth-century scientific discovery offered a framework for adventure novels where the science of the day played an important role.”

Indeed the science was accurate, but it required a hundred years or more for technology to advance to the point where his inventions and adventures became reality. The traversal of the Arctic Ocean under the ice in 1959 by the USS Nautilus made a reality of the undersea adventures of Captain Nemo and his Nautilus. The Apollo project made From the Earth to the Moon . . . a preliminary exercise. Even the fanciful balloon voyage across Africa in Five Weeks in a Balloon pales in comparison with current around-the-world balloon exploits.

Verne’s first novel imagined men floating almost helplessly across a largely unmapped Africa in search of the still-undiscovered sources of the Nile. By the time Around the World in Eighty Days was published, the planet had been crossed, demarcated, conquered, and exploited. The wonders Verne captured in Five Weeks in a Balloon were essentially gone by the end of his life. To this day, however, Verne challenges readers to explore new worlds while also mourning the passing of older, quieter ones, those immersed in mystery and ennobled by myth, which, like ours, are made up of stories. His novels may chart the disappearance of a world, but they also bring us the beginnings of a new one, the one we inherited from him.

2 Comments

I really enjoyed your introduction in this book but couldn’t find the translators anywhere. Is the ‘Around the World in Eighty Days’ one by George M Towle?

Yes, I believe Baker and Taylor used the Towle translation. They only use ones in the public domain, and that may be the best known one. Thanks for reading.