The editors at Plume magazine in Canada asked me to supply a short piece on first editions of famous works of poetry for their Essays and Comment section. Many thanks to essays editor Robert Archambeau for soliciting the piece.

* * *

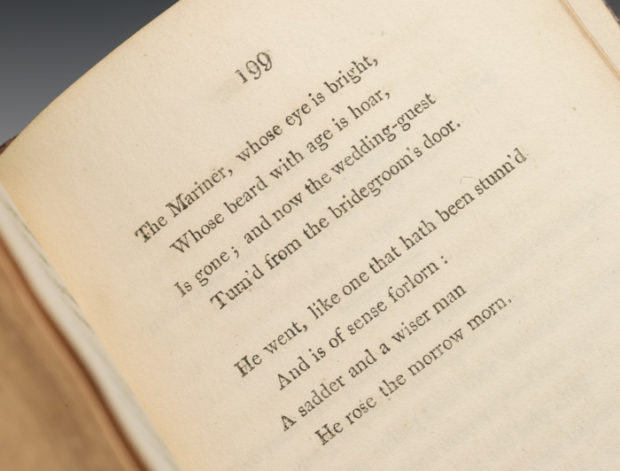

For a decade and a half I have worked more or less contentedly as a rare book dealer, roughly half the number of years I’ve devoted to being a poet, an equally eccentric pursuit. In that time I’ve had the pleasure of placing quite a number of extraordinary first editions of poetry into my clients’ collections. I am often asked what precisely makes a book “rare.” Why, for instance will one volume of poetry sell for $5 (a used copy of a recent title, something I would buy for myself), $50 (a first edition of Diane Wakoski’s 1966 Discrepencies and Apparitions signed by her along with a drawing in her hand), $500 (poet and translator Richmond Lattimore’s copy of the 1955 first edition of Elizabeth Bishop’s second book Poems: North & South and A Cold Spring), $5,000 (an inscribed 1926 first edition of Langston Hughes’ The Weary Blues), while another might sell for $50,000 (a 1633 first edition of John Donne’s Poems by J.D. with Elegies on the Author’s Death), and yet another for well over $500,000 (Edgar Allan Poe’s impossibly rare 1827 first book of poetry, Tamerlane, authored by “A Bostonian,” which hammered at $662,500 at a 2009 Christie’s sale, a tattered and rather stained copy at that, but one of only 12 thought to remain from a print run of 50). While no easy answer concerning this sort of marketplace value will fully suffice, there are a few measures upon which one may fairly rely.

The historical significance of a book—which has much to do with cultural consensus and is subject to alteration—is perhaps the greatest determinant, as no other aspect will bear if the book is not thought important in the first place. The endless pull between a book’s desirability and its scarcity contributes enormously to its value as well. How many remain in the world, and how many in private hands? How many and what kind of collectors or institutions vigorously pursue it? Beyond these considerations one encounters bibliographical matters—state and issue points, most of which are imperceptible to the amateur, others scandalously contentious, others still evolving by comparison with newly discovered copies—and material attributes, such as overall condition, presence of original or early bindings, wide margins. There are also matters of provenance—copies that come down through libraries of famous scholars, collectors, or friends of the author, and much else besides. To read a poem in its first edition delivers an experience akin to the “aura” that Walter Benjamin insisted an original work of art possesses—“the uniqueness of a work of art is inseparable from its being embedded in the fabric of tradition”—and which is diluted through reproduction down the ages. It is quite something to read Paradise Lost in its first edition of heavy paper bound in centuries-old calfskin, quite another to do so with a footnoted, small-type, tissue-paper classroom doorstop. Whatever magic may have attached itself has flown.

Read on over at Plume.