The tranquil River carried me downstream

as tribal warriors slashed the hauler’s throats;

my ropes went slack, and I could live my dream!

They nailed the naked crew to painted posts.

I didn’t care about the slaughtered men,

the Flemish wheat or English cotton freight.

When all the mayhem settled down again,

the River taught me how to navigate.

I ran through winter heedless as a child,

through raging storms and riffling, surging tides.

Triumphant over chaos, I ran wild!

Peninsulas began to shift and slide.

The storm blessed my awakening at sea.

Light as a cork, I danced upon the waves

that roll the dead in shrouds and set them free.

Ten nights, and I don’t miss those empty lamps.

Like sour apples tasting sweet to children,

the green sea seeped into my hull of fir,

rinsed out the puke and blotches of blue wine,

and swept away my grappling hook and rudder.

And then I bathed in the Poem of the Ocean,

infused with galaxies of milky stars,

devouring greens afloat in turquoise flotsam,

the thoughtful drowned, with pale blue scars,

the sudden stain of blue delirium,

intoxicating rhythms under spirals

of gleaming light, perhaps a requiem,

fermented, bitter, played on lovestruck lyres.

I’ve watched the sky explode with lightning spark,

watched waterspouts and swirling tidal streams,

observed the flight of doves around dawn’s arc,

and seen what other men have only dreamed.

I’ve watched the sun grow dark with mystic dread,

ablaze with streaks of ultraviolet light;

the gleaming waves still shudder with the dead,

a re-enactment of an ancient rite.

I’ve dreamed of green nights, dazzled by the snow,

of kisses climbing up the oceans’ eyes,

and brilliant blue and yellow saps that flow,

awakening the singing phosphorus.

Through pregnant months, I’ve followed tidal swells,

hysterical as herds assaulting reefs,

without thinking of Mary’s luminous

feet, battered by the snout of windblown seas.

You know I’ve struck amazing Floridas,

mixed flowers and panther’s eyes in skins of men,

and followed rainbows’ bridals to green herds

that graze beyond the ocean’s last horizon.

In putrid swamps I’ve seen humungous traps

with crocodiles decaying in the reeds.

I’ve seen calm, shattered by a wave’s collapse,

whirlpools that circle down the dark abyss,

silver suns, pearly water, glaciers, skies,

hideous shipwrecks sunk in murky seas,

and giant serpents feasted on by flies.

I’ve smelled the stench among the twisted trees.

I wanted children’s eyes to see these fish

that swim in blue waves, golden bream that sing

of foam and flowers appearing in my visions

and powerful winds that heave me up on wings.

I’ve rocked so long upon these sobbing seas

that offered me their yellow-suckered flowers,

and I’ve remained a woman on my knees,

at times a martyr, tired of zones and poles,

almost an island, fed up to my gunwales

with blond-eyed birds dropping their slime and gossip.

I’ve sailed on as the drowned began to funnel

down backwards through frail ropes and fall asleep.

And I, a boat lost in the hair of bays,

tossed by the wind into the birdless ether,

my water-drunken carcass won’t be saved

by Hanseatic Coastguard ships. I’ve slithered

free, frothing, riding violet twilight haze.

I, who shot through the sky, a glowing dyke,

who fed the poets jams and marmalades,

the snots of bright blue sky, and sun-blanched lichen,

I ran! Blotched by electric crescent moons,

a mad plank, pushed around by black sea-monsters,

I fled July’s hammering heat, the noonday

skies, that brilliant blue, those fiery funnels.

I, who shook, hearing moaning Behemoths

some fifty leagues away, and raging whirlpools,

eternal weavers of unmoving blues,

I miss Europe, her old protective walls.

But I’ve seen archipelagos of stars,

delirious heavens that open wide for sailors—

Are you exiling yourself in slumber,

O million golden birds, O rising vigor?

But now, I’ve wept too much. I’m in a funk.

And every moon is horrible, every sun

is bitter. Love is toxic, swollen, drunk.

O let my keel break; let me come undone.

If I want Europe’s water, it’s a cold

black puddle, where a sad child crouches down

to push a boat, as fragile as an old

butterfly, toward the setting sun.

No longer can I, tossed by weary waves,

drift in the wake of schooners full of cotton bales.

Nor can I cross the pride of flags and flames,

nor swim beneath those ghastly eyes of floating jails.

First appearance in Blue Unicorn, Volume 40, Number 2, February 2017

John W. Steele, upon entering his seventh decade, began winding down his career as a psychologist and exploring his long neglected interest in poetry. He is pursuing an MFA in Creative Writing at Western State Colorado University. John has published poems in Blue Unicorn, Lyric, and The Classical Poet. He lives in Boulder, Colorado.

Translator’s Note:

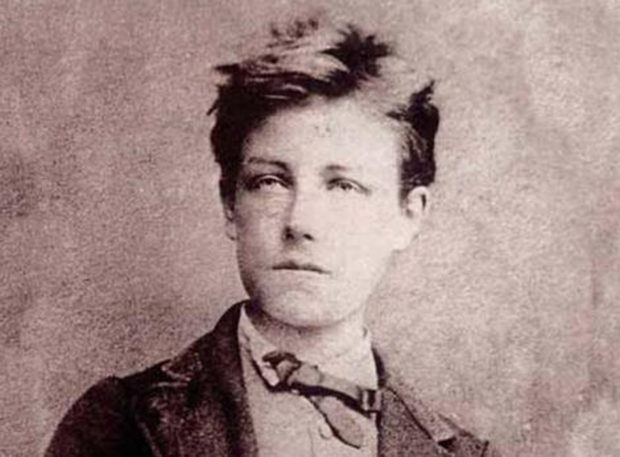

Arthur Rimbaud, the hugely influential nineteenth-century French poet, remarked in a letter to his friend, Paul Demeny, “the poet makes himself a seer by a long, prodigious, and rational dis-ordering of all the senses.” A famous libertine and restless spirit, his work, all of which he com-pleted before the age of twenty-one, prefigured modernist poetry and surrealism. Although his use of language in “Le Bateux Ivre” is chaotic, extravagant, and at times disjointed, Rimbaud contains this anarchy within a precise and orderly alexandrine verse form with a-b-a-b rhymes.

Surprisingly, very few of the widely available translations follow Rimbaud’s example. Notable exceptions include those by A.S. Kline and Paul Schmidt, written primarily in iambic pentameter lines, and the Brian Aspinall, in iambic trimeter. Because it is much easier to rhyme in French than English, it comes as no surprise that I was unable to find a single translator who maintained a rhyme scheme throughout the entire poem. In my view, translations that do not adhere to regular meter and rhyme fall short of presenting the rhythmic counterpoint of chaos and order that

Rimbaud reveals in the original poem.

In light of this, I have endeavored to break new ground by composing every line—with the

exception of two hexameter verses in the last stanza—in iambic pentameter, and by including at least a hint of a-b-a-b rhymes in every stanza. Whether translating, or composing original poems, I find the discipline of following a metrical pattern functions as a powerful generator of verse. It seems that the Muse is attracted to the sweat on the brow of a poet practicing metrical verse-craft, and swoops down, again and again, to lend a hand, suggesting alternative words, phrases and rhymes, that otherwise would never have been dreamed of.

No Comments