Poets are sometimes sought for interviews, perhaps not as zealously as are pop stars and politicians, but, still, it happens. I’ve been interviewed on a number of occasions, a few times on public radio, other times for print or online literary journals, but I must admit that until now I’ve never been interviewed by a professional investigator. I quickly learned that a detective, working in his spare hours, can put the screws to a poet in ways that critics and radio hosts wouldn’t dream of (and he doesn’t even need the megawatt overhead light or a bucket of cold water to do so). In truth, we stuck to the poems, their origins and impacts, what they mean to me, and what place I hope they might find in our culture.

The year-long interview by Mark Danowsky, who is also a poet and managing editor of the Schuylkill Valley Journal—where the interview appears—turned out to be unexpectedly voluminous, so much so that a great deal of the original had to be cut in order to bring it in line with accepted publishing practices. Still, what remains is impressive in its size, if nothing else. Mark brought unprecedented attention to my poems, which he reads with intelligence and care that I found impressive and, in fact, quite humbling. With the magazine’s permission, I reproduce the interview below.

Print copies of the issue (Schuylkill Valley Journal #44: Spring 2017) are available on Amazon. You may also contact Mark Danowsky, the magazine’s managing editor, if you are interested in a copy.

FOREWORD

When the opportunity to interview Ernest Hilbert arose I immediately returned to his earlier collections, Sixty Sonnets and All of You on the Good Earth, before delving into Caligulan, his third collection, which was recently awarded The Poets’ Prize. This felt essential in order to properly track Hilbert’s development as a poet. In the interview, I ask about changes in his speaker’s sensibilities. Hilbert responds, “The despair experienced by the characters in Caligulan can be understood as the kind of exhaustion that results from the unrelenting disquiet of the first two books.”

I was delighted Hilbert agreed to my request for a long form interview with the hope of revealing life and relationship growth over the course of our exchanges. And so we have what I like to call an evolving interview. In this interview Hilbert unpacks his poetry, discusses his life as a rare bookseller, and shares his experience collaborating on the creation of an opera.

Engaging with Hilbert you quickly understand the wealth of knowledge he wields. Hilbert’s poetry matures with each new collection. His ear for music is unparalleled. He writes for the modern reader, but his work will live on because it does not depend on the fleeting politics of now to be understood. The blend of tradition and contemporaneity ensures that each Hilbert poem you encounter delivers meaning and voice—a recipe for lasting work. The act of reading Hilbert’s poems teaches us why we need them.

– Mark Danowsky, Managing Editor, Schuylkill Valley Journal

Mirror in the Shadows: An Interview with Ernest Hilbert

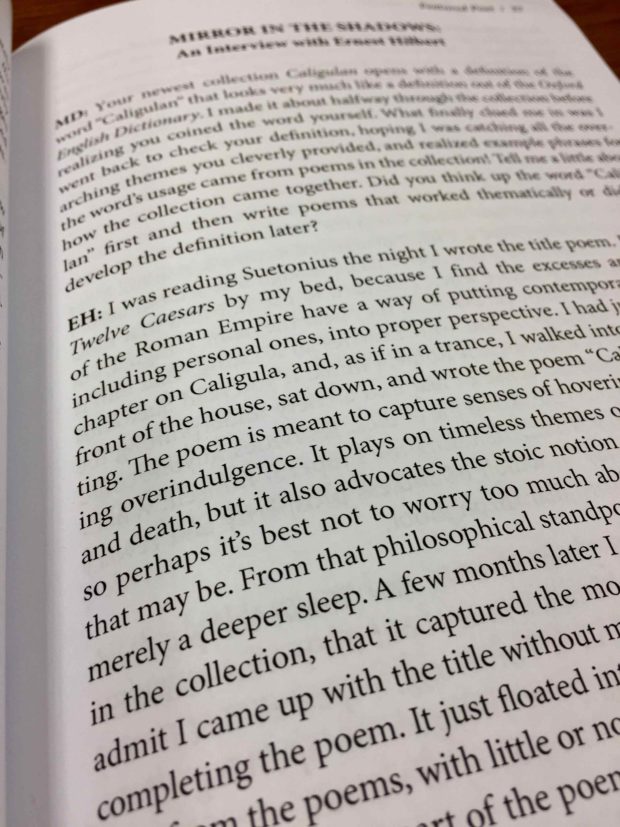

MD: Your newest collection Caligulan opens with a definition of the word “Caligulan” that looks very much like a definition out of the Oxford English Dictionary. I made it about halfway through the collection before realizing you coined the word yourself. What finally clued me in was I went back to check your definition, hoping I was catching all the overarching themes you cleverly provided, and realized example phrases for the word’s usage came from poems in the collection! Tell me a little about how the collection came together. Did you think up the word “Caligulan” first and then write poems that worked thematically or did you develop the definition later?

EH: I was reading Suetonius the night I wrote the title poem. I keep The Twelve Caesars by my bed, because I find the excesses and outrages of the Roman Empire have a way of putting contemporary problems, including personal ones, into proper perspective. I had just finished the chapter on Caligula, and, as if in a trance, I walked into the office at the front of the house, sat down, and wrote the poem “Caligulan” in one sitting. The poem is meant to capture senses of hovering dread and shocking overindulgence. It plays on timeless themes of uncertainty, anxiety, and death, but it also advocates the stoic notion that death is inevitable, so perhaps it’s best not to worry too much about it day to day, hard as that may be. From that philosophical standpoint, death is understood as merely a deeper sleep. A few months later I realized it was the key poem in the collection, that it captured the mood of the book, and I have to admit I came up with the title without much thought immediately upon completing the poem. It just floated into my mind. Most titles rise naturally from the poems, with little or no deliberation on my part, because a title is really only a part of the poem. It’s like naming a pet, in a way. You glance at it as it strides into the room, and the name comes.

After I assembled the collection, I decided that “Caligulan” would serve as an apt title for the book, less generic than Sixty Sonnets and not nearly as unwieldy as All of You on the Good Earth. Roman writers were chattering in my head. I had also been reading Juvenal, Horace, and Catullus, largely because I was teaching a course on the history of verse satire. Combined, these influences placed me in a pagan imperial frame of mind, you might say. Stylistically, the poem combines comedic, satirical, and tragic elements from my first two books. In review, I feel the poem draws in equal parts on “Prophetic Outlook,” “Drop Out,” and “Home Security,” though I was not thinking of those poems at the time.

As for the faux dictionary definition that begins the collection, I was motivated to add that a bit later, after the book had been accepted for publication, in that waiting-room period between when a book contract is signed and the last possible day that changes can be made to the manuscript. That can be a very fertile time, and that is time I devote to what might be called extra-poetic aspects of the book. I spend a lot of time coming up with book cover concepts and hidden jokes that are realized sometimes only years later. Since “Caligulan” was, after all, a more or less new word, at least as I used it, I felt it demanded its own definition. It has existed for some time as a descriptive term, though it is seldom used. I hadn’t encountered it before when I decided to use it. I find that most people think of hedonistic excess when they hear the name Caligula, but that’s largely due to the 1979 film, which carries an X rating. That film is more about the 1970s than ancient Rome, I think. If you read Suetonius carefully, what you find is a sense of fear and anxiety underpinning the extravagance of Caligula’s rule. Amid the endless festivities, anyone could be killed at any time on a whim, including the Emperor himself. What I found intriguing is the way in which boundless prosperity and revelry could be colored by dread and fear throughout.

MD: You mentioned the title poem in Caligulan “draws on” poems in your two earlier collections. Let’s talk a little about the poems you mentioned. “Drop Out” has, and tell me if I’m wrong, a speaker that is very different from you. I’m wondering your thoughts on speaking in the voice of others, on behalf of others—the poetry of witness.

EH: The raw material for “Drop Out” appears in stories my wife told me about her life as an undergraduate in the 1990s, when she was studying archaeology and history in Arizona. I brought the scene up to the present with a reference to the “dreaded text.” Audiences get that one instinctually, the painful time spent waiting for a return phone call from someone only to get a perfunctory, unemotional text instead. The dark humor at the beginning relates a simple fact of life without health insurance. I spent my adult life up until my mid-30s with no coverage, and Lynn was in a similar situation. The wet laundry image came to me while I was actually doing laundry. “Your life piles up like wet laundry.” I was lifting wet laundry on a humid day, and articles of clothing were falling out of my grip, and it felt bizarrely heavy.

MD: Do images for poems often come to mind while you’re preoccupied with mundane activities?

EH: Images come to me while I’m cleaning the house, doing the dishes, cooking dinner, sifting the litter box. That’s why I have a poem called “Dishwasher” in Caligulan. I haven’t yet mustered the requisite energy to write about the cat box, but it could happen. My wife hates laundromats, so the image of the heavy, wet laundry felt like a way of conveying a life that had grown weighted down with trouble, exhausting and also unmanageable. For years, my wife and I dragged our laundry to local laundromats. Once, when I was out of work, I was doing the laundry by myself while my wife, then my girlfriend, was on an archaeological excavation in Italy for the summer. While I was there, a man stabbed another man in the eye with a knife after an argument arose over clothing that was inadvertently mingled. There was blood everywhere. I remember it very clearly. The guy used a balled up white t-shirt to stanch the blood until the ambulance arrived. Everyone was frozen. No one wanted to call 911 or help the guy at all. Finally, the owner of the laundromat called the police.

All this builds up until we have the screams at the end. I meant that to be ambiguous. It can be read two ways. First, that the character is suddenly screaming uncontrollably and hearing the screams as if they belong to another, as if she has become emotionally dissociated from her own circumstances. Second, there was a mass shooting at a university when I was working on the poem. It was the Virginia Tech massacre. I thought to myself “that’s all you need, with everything else going wrong in college. Some guy comes in and starts shooting everyone.” You refer to poetry of witness, but I feel that sounds too grand a way to describe what I do. Most of the stories in the poems come from people I know or once knew, or things that happened to me. I don’t cull stories from the New York Times, the way some poets do, striving to be topical or somehow socially relevant. I find it amusing when critics suggest I take stories from newspapers or other news sources. They can’t imagine any other access to such stories. One last comment on the poem. I chose to make the title two words rather than the single word, “dropout,” because I wanted it to be both indicative and imperative. In other words, as two words, “Drop Out” can refer to the person who has finally had too much and decided to drop out of school, or even life, but may also refer to the directive that you must drop out, that you are destined to fail. That’s how it feels sometimes. You have to resist it.

MD: Your poem “Home Security” contains the phrase, “run for your household gun.” Is the word “your” in “your household gun” present in the poem for its sonority or is there another reason? I ask specifically because the idea of a “household gun” seems bizarre to me.

EH: Everything I write has an acoustic component, so the effect you suggest is one of the reasons I chose that term, but the sense of it is equally important. The notion of a “household gun” may strike you as odd, but it would not seem so for many Americans. The term “household” is used to make the gun seem an everyday object, like a screwdriver or kitchen appliance. It’s a part of American culture, even if it is not part of mine or yours. I’m more of a sword guy. One in three Americans owns a gun, and not only one gun. Remember, this is a satire about a person who cannot feel safe, whatever measures he takes. “You might trail it with mob and open noose, / But it escapes, if it were ever there.” He imagines himself part of an angry mob, a vigilante, but also someone securing his own property from invaders.

MD: In “Prophetic Outlook” you write, “Maybe you’re really sick. It’s hard to tell.” Throughout your first collection, Sixty Sonnets, your poems’ speakers seem to question what is going wrong or what has gone wrong as compared to the sensibility of your speakers in Caligulan where the reader consistently gets the feeling something wicked has arrived. Put another way, the questioning speakers of Sixty Sonnets are replaced by Caligulan’s speakers, who are convinced something is most definitely wrong. Is this a fair assessment?

EH: That is a remarkable observation, and I think it is correct. Maybe the feel that something wrong suddenly tipped over into a certainty that something must be wrong. That’s certainly an inauspicious direction for the poems to take. The uncertainty that pervades the first book is intended to create a sense of uneasiness, though I believe one must soften attitudes and learn to accept uncertainties. Terrible things can and do happen. Some things can be prepared for or prevented, but threats to our well-being are always there. This may be more keenly felt in Philadelphia than elsewhere. I don’t know. The despair experienced by the characters in Caligulan can be understood as kind of exhaustion that results from the unrelenting disquiet of the first two books. But, again, let us not forget that “Prophetic Outlook” is also a satire. I wrote my doctoral dissertation at Oxford on apocalyptic writing in the First World War. I had to dig down to the roots of that kind of thinking in order to understand it, beginning with Zoroastrian and ancient Jewish writings, right up to the twentieth century. Let me put it this way. The world has been ending for a very long time.

MD: So you’re not in the camp that believes the end times will arrive in our lifetime?

EH: What you begin to realize is that belief that matters can’t get any worse, or are quickly worsening, and that some cataclysmic reckoning is at hand, is an age-old feeling. Often, the thought that the world is falling apart is merely a way of expressing that the person who believes it is falling apart. I sometimes say, the world isn’t ending; you are. So “Prophetic Outlook” is poking fun at people who only see the worst all around and consequently lose any sense of perspective. I wanted the bleak complaints to suddenly be caught up short in the closing couplet of the poem. The speaker’s inability to determine if he is, in fact, really sick or not underpins the whole poem. Matters seem to worsen, but who can tell? From whose perspective are things worsening? That crick in your neck could be deadly. Or it could just be a crick.

MD: Sometimes you write about small moments. In your poem “∞” (infinity symbol), from AoYotGE, you write about, “A rubber band, very easy to miss, / Forming the sign for ‘infinity,’ a full, / Conspicuous Circuit.” Reading this poem, I was surprised how many different ideas were sparked in response. There’s an existentialist concept, I believe, about the notion of encounter, about existence based solely on your continual engagement with the object of your attention or gaze. The poem also made me think of “Shall I project a world?” from Pynchon’s Crying of Lot 49 and “Do I dare / Disturb the universe?” from Eliot’s Prufrock. What I’m getting at is that you managed to grow the small moment, a seemingly simple observation, and maybe that’s part of the reason why the infinity symbol is such a perfect image.

EH: I was hunting for poems one day while walking from the subway stop to work along 15th Street in Philadelphia when I alighted on the notion that the search for the subject could itself easily serve as a subject. I too am steeped in Pynchon and Eliot, and, though I don’t read them as much as I did when I was young, they make up a part of my mental furniture, so you’re not wrong to suggest those passages as parallels. The poem is about encounters with the world and the human activity of creating meaning in those encounters. I include mention of the Möbius strip, which is mathematically non-orientable and consists of a surface with only one side and one boundary that runs forever in a closed circuit. I pictured the universe as infinite but closed. You can travel the extent of the surface and return to the starting point without encountering an edge or boundary. It occurred to me at the same time the symbol for infinity came to me, and that is simply a visual equivalent. It just happens that the rubber band I saw that morning had assumed that figure when it was discarded.

It’s also a poem of enlargement, pulling more and more meaning out of a single moment of discovery. There it was, in the “silted gutter, edged by gravel, / Flanked by cigarette ends, receipts, and leaves,” among detritus and dead things, itself trash, yet somehow seeming more permanent than its surroundings and also more symbolic. If I had simply titled the poem “Infinity” it would have lost a lot of its energy. I decided to use the symbol for infinity, which, incidentally, is called the lemniscate, which is an 18th-century term coined by Johann Bernoulli that simply means “decorated with ribbons” in Latin, though the symbol itself can be traced back to ancient Greek mathematicians. The speaker of the poem questions the nature of his observation, asking “am I simply naïve” but resolving that perhaps “it’s not so strange at all.” The observer brings the meaning, but cannot always take the meaning, which is to say both that he cannot take it away after the event and also never truly “take” the meaning, which is how the poem closes, “When I walk away, will it keep what it meant?” In other words, the world has meaning beyond what you bring to it. Whether or not that matters to you is another consideration. The poem plays with the divide between the noumenon, or thing-in-itself, and the phenomenon, what is experienced by the senses. It’s also a study in the role and activity of the poet when interpreting events, objects, or even thoughts into verse. It’s about making poems. The origin of the word “poet” in English is from the Greek, poetes, “maker.”

MD: By contrast, in “Squirrel Hill,” from Caligulan, the world seems to somehow shrink as the poem moves along. Does that make sense?

EH: The poem is about the dwindling of possibilities that accompanies age. The couple described in the poem is trapped in a weakened relationship, captive in jobs they can’t stand, imprisoned in a house they can’t sell, and yet they are brought together emotionally one last time by the pain caused by the death of a pet cat. The pain serves to join them in a way nothing else could at that point, but even the pain and the mourning are temporary. The old troubles will return, and this is suggested by the grim closing couplet, “Our time, and our love, too small, in past tense, / In the ever-shrinking lands beyond the fence,” which owes a debt to Philip Larkin’s “Wires,” about young, daring cattle becoming “old cattle” from the day they first run up against the electric fences and are shocked. I should point out that it was not a conscious allusion to his poem but rather something that simply came to me while I wrote the poem and which I noticed only later. In Larkin’s poem the world grows smaller because the cattle realize they are trapped inside the fence. In my poem, it becomes apparent when looking past the fence that there aren’t as many prospects as there once were. The world outside the fence has shrunk in the time that was spent inside it. So, yes, to answer your question, the one poem is about enlargement of possibilities and the other about the closing down of options.

MD: Related, in a way, are poems like “Handlers,” from Caligulan, as well as “Song,” from Sixty Sonnets

. I’m a big fan of poems like “Handlers” that attend to the grace, in terms of motor skills, people manage to automate. “Such Art!” as you say in the poem. Not too long ago I stood and leered at this guy making pizzas. Obviously no one likes being openly stared at while they work, right? I wonder what the pizza maker would have thought or said had I told him I was a poet and found his art inspirational. What do you hope to achieve in a poem like “Handlers”?

EH: Well, “Song” is a celebration, a toast, to those who feel out of place in a disposable commercial society, a society that seems to have gone haywire, and who revive and preserve older ways of doing things, activities that attach their lives to the world in a more meaningful way than they might attain as passive consumers. When I was a boy, my father used to tell me “you can be a creator or you can just be a consumer.” In a sense, “Song” can be compared to “Handlers,” in that it praises physical work, but the poems are also very different. “Song” is simple. It is about attitudes and ways of living. It doesn’t hide anything. “Handlers” is meant to be more challenging. I was watching the baggage handlers at Denver International Airport one summer on my way back from teaching at the MFA at Western. I imagined closed baggage carts—the ones that are linked together into little trains with curtains that close in the front for rainy weather—were little stages being pulled into position. I envisioned miniature dramas acted out on them. That put me more in the mind of watcher and watched. I put the “Such art!” and the reference to English landscape artist Constable into the poem to signal this. I was thinking about the related roles of artist and audience. The poem is also an appraisal of two worlds, one of physical exertion in dangerous conditions as it relates to leisurely, air-conditioned waiting, server and served. The poem ends on an ominous note:

They thrive in the dire heat,

While we, clutching carry-ons,

Await our appalling departure

Onto overseen routes.

The title, “Handlers,” was meant to refer both to the work, the handling of bags, and to the notion of handlers, those who control the elderly, the sick, animals, or celebrities who have difficulty with boundaries. In a world of boundless freedom, do we yearn for handlers?

MD: Tell me about your poem “Mayfair,” which seems like the flipside of “Handlers.”

EH: They both concern observation, one commenting upon the helplessness of a leisured class and the other about predatory nature of celebrity-watching. “Mayfair” was inspired by a visit to NOBU, courtesy of a young, well-heeled book collector I met at the London International Antiquarian Book Fair at the Olympia in London. He insisted he take some of us out for dinner and used the concierge service of his American Express black card to secure the reservation. It was a great time, as you might imagine, and amid the single malts and sushi I would step outside now and again for a cigarette. Outside the entrance to this exclusive restaurant were two men, one, a photographer, alert to any opportunity to photograph a celebrity, the other, a beggar with a cup. The photographer struck me as a sort of soldier or hunter, aiming his camera, thus the camera’s strap is “Like an archer’s vambrace / To hold his Nikon in place,” which also supplies a nice rhyme in an otherwise unrhymed poem, just as his modern role rhymes with those of his historical ancestors. The mortifying anecdotes related in the poem were told to me by the paparazzo himself while I smoked. Incidentally, the “drummer” in the poem was Roger Taylor of the band Queen. I forget who the model or actress was. The poem visualizes a world in which the elite class is hunted and constantly humiliated by a mass culture that elevates and also assaults its members.

MD: In your explanation of “Drop Out” you mention a need to resist negative thoughts. This brings to mind “Man’s Home, His Castle,” from AoYotGE, in which you write, “In cold circuits of a small, lonely noon, / And then retreating to bed far too soon.” I wondered about your qualms with the desire to call it a night early. It sounds like you may have been making a point about mental health in the poem.

EH: Well, to be clear, we should not resist negative thoughts, though we should not allow them to consume us. In the broadest sense, I think of life and energy of any kind a rare thing. Life is always struggling to stay up above the abyss from which it emerges and to which it will return. The flower reaches for the sun. A predator preys. A fire grows until it has consumed its fuel. I feel we are constantly tugged downward, and eventually we go down for good. I suppose Freud described it as Thanatos, the urge toward destruction and death, and its entanglement with Eros, the urge toward creation and vitality. I’ve been criticized for that poem and others like it. I’ll quote from a review in New Pages: “I don’t know a writer who doesn’t struggle, but the speaker in Hilbert’s lines seems to be especially down on the times and himself. It is an aspect of the collection that is both depressing and invigorating. Without this honesty of character, we might not learn much about the perspective of the speaker and why we should pay attention—but the pall of negativity got occasionally wearisome to this reviewer.”

The poem does not function as commentary at all. It’s simply a description of one of those days that never gets off the ground. You rise from sleep, and you’re supposed to have energy, be alive and engaged, and at the end of the day you’re exhausted from that activity and you fall back to sleep. Not every day works like that. Some days you can’t do it, but you have to bring yourself back eventually. It plays on the absurdity of the phrase “a man’s house is his castle.” He’s hardly a king when he’s trapped in it, helpless, unable to face the day. I was reminded of those days in graduate school in England in the winter when a pallid sun emerged around 10AM and was already leaving at 4PM, concealed by clouds the whole time. It’s about a day when life is occluded, but the character is not defeated, only too tired to bother with much more than reading and listening to music and the going back to bed. Maybe I had a hangover the day I wrote it. Also, what you refer to as “negative thoughts” are, in fact, self-reinforcing, as has been proven in numerous studies. There is something to the “think positive thoughts” philosophy, but it’s not really a way to live one’s life. Americans somehow feel they’re supposed to be happy and content all the time, that if they’re not something is wrong and that state must be corrected. I prefer to think that contentment and happiness are fleeting and unpredictable, and that they are all the more valuable for that.

MD: Thanks for using the word “odd” earlier. Odd is very much an Ernest Hilbert word. The language of war and regalia come into play often as well. You mentioned being “a sword guy” and “blade” is a word in your arsenal. “Shell” is another. There is certainly talk of lords and fortresses scattered on the battlefields of your collections… “Judgement,” from Caligulan, for example. The poet Richard Hugo talks about the words you “own” in his classic text The Triggering Town. Do you have a sense there are words that are particularly loaded and more meaningful to you?

EH: Well, I am odd. Maybe we all are, and some are simply better at keeping up appearances. Yes, the language of armor and weapons has always appealed to me for some reason, the machinery of assault and defense. Words are used this way all the time by anyone who has real control over them. The talk of Myrmidons and fortresses in “Judgement” is part of a larger effort to make the experience epic and heroic. It would be too easy to be ironic and degrade the characters in the poem. It describes the experience of performing heavy metal on stage before a whipped-up audience. There’s nothing like it. It’s a transcendent experience. I recently dove into an fierce pit at a Slayer concert with my brother. The next morning I developed a limp that lasted for about a day, and for a week I had welts and bruises on my arms and rib cage, which are the points of maximum impact. But I loved it. It was an ecstatic, dreamlike hour. You connect with complete strangers, literally, slamming into them but also helping them if anything goes wrong. I went down once, and I was pulled up immediately to my feet. After a Slayer pit, I walk down the street remade, unafraid of any threat. When the guitarist in the thrash metal band Judgement—for which I was the bass player for a number of years—unearthed a vivid photograph of us performing at a club called Bonnie’s Roxx around 1990, I immediately knew I wanted to recapture that feeling somehow, so I went big with the words. Violence is endemic to heavy metal music, the lyrics, the crowds, so it works. I understand the antique quality of many of the words I use, but they are also a nod to the birth of the sonnet in English, Wyatt and Surrey, Tottel’s Miscellany, Spenser, the way a modern artist might nod to some facet of antiquity or classical art by way of establishing a connection, emphasizing the distance we’ve come, and also simply as homage to earlier masters. Also, since I was a boy, I have loved objects that are armored and offer protection—tanks, battleships, chain mail, fortresses. No doubt it was part of a vague fantasy of being able to protect myself from physical attacks I suffered routinely at the hands of stupider, angrier, tougher boys.

MD: You mentioned your time at Oxford. I wondered about the lasting impact of your education overseas.

EH: The most important aspect of my time there was the work on my dissertation with Jon Stallworthy, who was a true gentleman. I also had classes with living legends, such as John Bayley and John Carey. I sat in seminars on modern poetry with James Fenton, who was Oxford Professor of Poetry at the time. I also started a magazine with a friend that allowed me to publish all sorts of poets. Marjorie Perloff, Seamus Heaney, and Iris Murdoch were on our advisory board of editors. I found the English were mildly curious to learn more about modern American poetry, so I published Charles Wright, Anthony Hecht, Charles Simic, W.D. Snodgrass, Jorie Graham, Galway Kinnell, Caroline Kizer, Adrienne Rich, Donald Justice, Philip Levine, Mark Strand, John Hollander, and Marilyn Hacker, as well as an essay by David Mamet, with whom I struck up a correspondence (based on my love of the film and play Glengarry Glen Ross), and other poets, including Les Murray, Christopher Middleton, Andrew Motion, Michael Hamburger, and Charles Tomlinson. On balance, I’m very glad I went over to Oxford for graduate school, though I’ll be paying the loans on it for the rest of my life, even with the very generous scholarships provided to me by the British government, which allowed me to attend.

MD: Finally, we have arrived at trash. Trash/debris/detritus is named in many ways and forms throughout your collections. Why has literal garbage piled up in your poems?

EH: Well, it’s all around us, hard to ignore. It goes without saying that most Americans have adapted to a disposable economy. The amount of packaging that confronts us daily is almost overwhelming. The rapidity with which appliances and products break down and stop functioning is astounding, and we are offered fewer and fewer alternatives to this life. However, that’s not my main concern when I use trash or debris in my poems. Trash is not only made up of waste. Trash is sometimes treasure. Some of the rarest documents and pamphlets are valuable to us precisely because they were not meant to last. What is ephemeral in one age is prized in another. My wife, Lynn, is the Keeper of the Mediterranean Section at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. She has spent summers at excavations for much of the past decade, first at the Poggio Colla site in the Mugello Valley in Tuscany, where an Etruscan acropolis is being uncovered, and at Gordion in Turkey, the site of King Midas’s tomb, also where legend has it that Alexander the Great cut the Gordian Knot.

She tells me that much of what is learned at archaeological sites around the world is gleaned from waste. She has worked with paleoethnobotany, separating organic matter from inorganic in order to learn more about culinary culture and agricultural activity. What we do not intend to leave behind is as important as what we claim for posterity. The traces we leave behind are part of history, however small they may be. I suppose this is what we call material culture. One of the problems with culinary history is that the written records reflect the experiences and knowledge of only those who could read and write, obviously. This is why Terry Breverton, in his book The Tudor Kitchen, attempts to “reconstruct what people ate from the utensils they had in their kitchens,” for instance. Archaeologists in England recently worked out the extent of black plague deaths by measuring the density of pottery shards found in waste pits. The massive drop in the amount of broken crockery indicates how many fewer people there were left to accidentally drop bowls and plates on the floor. The pyramids tell us much about the social order and religion of the ancient Egyptians but not a great deal about how they lived their daily lives. Before spending time at ancient sites, Lynn worked in landfills here in the United States as part of the Garbage Project with Bill Rathje, who led teams of trained archaeologists, called garbologists, into landfills and other places. Wearing hazardous material suits, they would dig right down into landfills to learn about what is really discarded in America and by whom. Sometimes there is a gulf between what people say and what they do. They learned that wealthier Americans underreport the amount of alcohol they consume, for instance, as evidenced by the bottles they leave behind. This is why celebrity stalkers and detectives go through garbage. We are what we consume and abandon.

Not surprisingly, the Germans have a word for it, ruinenlust, which means “feeling irresistibly drawn to crumbling buildings and abandoned places.” To me it’s a very romantic era pursuit. Think of Shelley’s “Ozymandius” or the moonlit landscapes of Caspar David Friedrich. Ruins are peaceful places to meditate on history, change, mortality. W.H. Auden remarked that “what really fascinates us to read about is a post-catastrophic society and landscape, abandoned ruins of once great cities, bad lands, roads overgrown with grass.”

This explains the popularity of surveys like Sir Walter Scott’s Border Antiquities of England and Scotland, with William Mudford’s engravings of ruins, or Robert Wood’s The Ruins of Palmyra. In these images readers behold splendors and magnificence of civilizations or eras of their own civilization that have disappeared. James Crawford writes in his book Fallen Glory that “cities thrive when remembering their unbeautiful roots in dirty industry and pungent compost of past lives.” I live in Philadelphia, which has been described as a stabilized ruin, and a day with a brisk wind will blow trash all over. The city is in a period of rebirth, though, which throws its crumbling and filthy aspects into high relief. We live in ruins to a certain extent. Even our house, a colonial revival over a century old, a brick structure with a stone foundation, is in constant need of repair and restoration. It’s almost like a living organism. I am sometimes reminded of how Faulkner writes in Requiem for a Nun, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” With this in mind, I begin the poem “Day in the Park,” which is really about disease, decay, and death, with images of debris:

The helpers sweep remains of past events,

Banks of crushed paper cups, banana peels,

Broken tape. Bored, they go about their chore,

And make the park the way it was before

The “Zombie Fun Run.”

I do something similar in “Suburban,” when, during a visit to the suburbs, I was gripped by the sadness of aging suburbs, of what is used up and the futility of consumer culture, the endless consumption that cannot fill a spiritual vacuum:

. . . wonder and waste of human wants,

Opened engine’s pooling oil, leaking vat,

Sap from a hacked tree, false gold of dripped fat.

Beyond the material aspects of what we discard, I thought of culture as well, the endless creative work that goes on to be forgotten, in this case books that are sloughed off by history in “Times Literary Supplement”:

Reviewers plough on, as careers rise and crash—

Few are prized, most pulped, conveyed to landfills,

Compacted like coal, toppled timber, great fossils.

On the subject of mortality, the dénouement of my poem “William James Still, Drowned in the Delaware River” is filled with litter. I wanted to close with a cinematic and symbolic look at what is finished. The boy of the title, William James Still, is a distant relative who drowned during a picnic.

The fairgrounds, littered with bunting and trash,

Grew cold also. Great bonfires sank to ash.

There is a purely human, biological aspect of this as well. Wealthy ancient Etruscans, Greeks, and Romans used instruments called strigils to scrape off dead skin and dirt once it had been softened by olive oil. This goop was then sometimes sold to the poor as if it had magical healing properties. What was scraped off of one person was valued by another. This final phase of “what we leave behind” is the very bedrock of my poem “Calavera for a Friend,” when I imagined what is quite literally left behind when we die, sometimes what is left of us physically.

Some small items might remain, artifacts,

Footnotes, fingerprints, cuff links, little anchors,

Small burrs that cling: initials carved in a tree,

Your name inscribed where no one will see.

On a more personal level, I was haunted by the thought that my father’s fingerprints may still be somewhere in the world. He died in 1992. His name appears in footnotes of published and probably forgotten books. Perhaps one of his hairs is still somewhere, not yet swept up. Lynn tells me she sometimes finds the fingerprints of ancient potters on pieces of pottery thousands of years old. We are spirit embedded in a form that grows frail, constantly changing and falling apart, while also renewing itself. Yeats writes in “Sailing to Byzantium” of being “sick with desire / And fastened to a dying animal.” The body you have now is not the same as the one you had five years ago, aside from some cartilage, maybe. All the rest has regenerated. You recreate yourself over and over again until you can’t do it anymore, and then you disappear, leaving behind whatever you loved most, wholly or in fragments.

MD: Earlier, you mentioned your work as an antiquarian book dealer. This seems like one of those dream jobs no one can actually get—like in high school wanting to work at a record store . . . and be John Cusack. How did this come to pass?

EH: I fell sideways into my work as a rare book dealer. I was living in New York, working at magazines and publishers, also at American Express, and when I moved to Philadelphia I worked for a while at the Wharton School while putting my resume in at employment agencies. Bauman Rare Books was expanding at the time, so I got the call. I was put through all sorts of tests, had to write essays and do assignments, also three rounds of interviews, and I got the job. I took it because I didn’t have health insurance and was deeply in debt. It’s an unusual field, rare books, and one given to all sorts of fantasies on the part of outsiders. I work at the company’s headquarters, in Philadelphia, and much of my work is no different from what you’d find in any other office job, which is to say that it has its attendant humiliations, frustrations, and tedium. I spend my days reading sales and activity reports, looking over auction catalogs, catching up on e-mails and returning calls. The difference is that I also get to work with books. Because we deal in many fields, from poetry to science, my interest is constantly shifting.

Right now I’m working with a collector who is building up his Byron collection, so I’m reading Benita Eisler’s Byron: Child of Passion, Fool of Fame, an exhaustive and fascinating biography. A project like this also allows me to do what I most enjoy, working with fellow dealers in Great Britain and North America to strike deals and assemble the complete works of the poet. I write essays for the client that explain a book’s place in the author’s life as well as our understanding of that author’s achievement and why the book absolutely must come to be housed in the client’s collection. This is the worthwhile part of it. The job has kept me near books, which is something that’s important to me. Many years ago, I was at a friend’s art gallery in downtown New York, and an old jazz musician told me “you’re either in your field, or you’re afield.” As a poet, I didn’t want to be too far afield from the world of books and literature. This job keeps me close to that world.

MD: Keeping with this line of questioning, what did you think of the movie The Ninth Gate (1999)? Yeah that’s right, the one with Johnny Depp and rare books allegedly written by the devil.

EH: It’s a perfectly awful movie. Really, just terrible. Both star and director have done good things, of course, but that’s not one of them. When I first started in the business, I was told to seek it out. I couldn’t believe how overworked and unpersuasive it was. The movie definitely plays to stereotypes, such as the mysterious contents of antique books (Stella Sung and I use this B-Movie ploy in our opera The Book Collector), the shiftless nature of dealers, trying to swindle enfeebled book owners, who are woefully unaware of a book’s value. Also, it’s just corny. But, then again, maybe some of it is true. I’ve seen all sorts of things in my time.

MD: All of your books have the feel of an art object—something you’d want to put on display. When you think about designing a book, and a book release, has your work as a rare book dealer affected your methodology?

EH: I expend a great deal of energy, perhaps too much energy, thinking about the physical aspects of my books. The back-handed compliment I usually receive from other poets is “oh, you’re really good at marketing and stuff.” This is meant to imply that I’m not a “pure” poet who gives no thought to anything else. Usually you’ll find they’re not very good poets anyway, so they may as well not think about anything else to do with publication. The various parts that make up a book, however tangential they may seem, are all part of a single artistic project, so far as I’m concerned. The poems are the thing, of course, and they must be as powerful and moving and fresh as possible, but there’s more. I’ve been lucky to have publishers that allowed me to hire my own designer to work on cover ideas I’ve come up with. I discard many ideas before settling on one I think will work. I pore over books of contemporary art hoping for inspiration.

MD: How did this come into play with Caligulan?

EH: The neon sign that was made for the photograph on the cover of Caligulan was inspired in part by the work of artist Jenny Holzer. I also liked the way red neon was used on the cover of the band Deerhunter’s 2013 album Monomania. I was also stirred by something I had seen. Out on Baltimore Pike, just outside the city limits, there is a massive cemetery called Fernwood. Across from the cemetery is a big brick building with heavy black steel bars in the window and only one sign of any kind, a bright red neon sign that says REFRIGERATION behind the bars. I stopped there one night and took a picture for reference. I don’t know why I was so taken with that particular sign. I love neon. I think it’s a truly American medium. It can be haunting and evocative. I took a writing job—I wrote an introduction to an anthology called Classic Tales of Horror—in order to raise money for the sign, which was manufactured by Jantec Sign Group in North Carolina. The sign’s deep blood red mesmerizes when you stare at it.

In fact, it’s such a strong light that photographing it became a problem. Matthew Wright, the photographer who took the pictures used on the front and rear of the jacket, spent a month scouting for locations. I told him I had an image of the neon reflecting on snow. Matt’s an adventurous photographer. For the photo shoot for my album Elegies & Laments, he hung himself backwards over the ledge at the top of a building twenty-one stories above the street to get a shot of me. He’s that kind of guy. He found the abandoned factory complex above the railway where we took those pictures. It was the dead of winter, freezing. We hauled the equipment and generator and lights through knee-deep snow. Our first photograph, which turns up on the back of the book jacket, was taken on the rail lines. We had to pull everything off the tracks every time a high-speed train whipped around the bend. Someone must have radioed in about us. Finally, we were confronted by representatives of the Federal Railroad Administration, who pulled up with spotlights on a special engine to throw us off the tracks. We had already taken a few shots by then, so we were fine.

We went up and over a bridge, where we hid some of the equipment behind the steel wall of the pedestrian crossing. We hung the sign up in one of the windows of the factory, and then I buried the power cable leading to the generator under snow banks. I crouched around a corner and Matt, who was across the street, would signal to me to switch off the generator while he left long exposures open on the camera. Otherwise the sign would be a solid block of crimson light. We’d snap off the power on the sign after maybe a second and he’d leave the exposure for another ten seconds to get it just the right heat, so to speak, for that cover. We were constantly ducking when local police patrolled through. By the end, my feet were no longer in pain because they were entirely numb. Lynn was there the whole time helping out, working as our spotter for trains and police. That story alone should give a sense of how much energy and thought I put into a book cover.

MD: What else is essential beyond the poetry itself?

EH: Books are not only the words on their pages. The words constitute a “text,” which linguists and theorists love. I’m more interested in books. Think of how much pleasure is derived from a well-designed album cover while listening to the music, or even a dazzling frame on a painting. We are physical beings in a physical world. Material matters give us gratification as much as the words, which also have physical properties, even if just vibrations in the throat and in air when spoken aloud. The poetry market is filled with amateurish book covers. If the cover is that much of an afterthought, why not just leave it blank but for the title in simple block letters and forget about it altogether? Why not just e-mail the Word document to friends? If you’re going to take things seriously you need to devote time, care, and attention. I used to hang the sign up behind me at readings. The sign now resides in my basement beside the television and the old Atari 2600 game console and cartridges. Sometimes I turn it on, and the red light shimmers on the wood floors.

MD: We’ve spent a good deal of time discussing the foreboding elements in your poetry, but there are instances of humor, lightness, and beauty. For instance, your poem “While You Were Out” ends, “When lightning poured rivulets of blue light / And ended, far off, before she saw it.” Okay, still ominous—but lovely! And then there’s a darkly humorous poem like “Bitter Beginning”: “And so goddamned much to do before work: / Drop the rental car off at the airport, / Leave shirts at the cleaner’s, post late presents.”

EH: The best poems in that book are the ones that harness the strong energy I wielded at the time to a very spare, vernacular language. I’m rereading Berryman’s sonnets right now, and I can feel that big, Elizabethan bountifulness pouring right over the top of the poems, frothing and boiling away what little meaning might be there. Usually, in those poems, it’s as simple as “I haven’t seen the woman I love for a week,” and we get these huge, ambitious lines about it like “O come we soon / Together dark and sack each other outright, / Doomed cities loose and thirsty as a dune.” I love this sort of thing and also worry about it. I’m drawn and repelled in equal measure. That tension is in my poems still, and I don’t know if it’ll ever go away. William Logan has commented that despite obvious gifts Derek Walcott has a tendency to create pretty language. “He could turn a cancer into a bauble from Fabergé.” Logan goes on to say that Walcott has none of “Lowell’s ravaging candor or unsettling mildness.” I reach for these Lowellian characteristics, though I love Walcott’s painterly descriptions. Walcott started out as a painter, after all. However, I believe that meaning can and must be embedded in physical description in order to matter most of the time. This is one of the reasons I admire Amy Clampitt. Just listen and see what she does in “The Sun Underfoot among the Sundews”:

But the sun

among the sundews, down there,

is so bright, an underfoot

webwork of carnivorous rubies,

a star-swarm thick as the gnats

they’re set to catch, delectable

double-faced cockleburs, each

hair-tip a sticky mirror

afire with sunlight, a million

of them and again a million . . .

When I use rich language to describe a scene or an object I’m doing so for two reasons. First, I’m trying to create an original language, say something in a way it has not been said, a fool’s errand some might think. So I reach and bend until it feels new. Second, as I’ve said elsewhere, we are physical beings, and we invest the physical world with symbolic import. The poet BJ Ward recently sent me a wonderful handwritten note to say that while he detects the influences of Lowell and Hecht in my poetry, he wanted to tell me that he heard Frost and James Wright.

Ward identified Frost in my attentiveness to details, which is true. He mentioned the early poems of Wright, as the restraints of verse began to fall away and he turned to what is known as “Deep Image” poetry. While I’ve never been drawn to Wright’s poetry, I always felt that the deep image concept had real potential, though it shaded away into the shamanism of Robert Bly pretty quickly. I do reach for a connection between physical and spiritual realms in the poems. That sounds outrageously grand, but it’s true. That’s why I linger on description of the material world.

MD: It sounds like you have a happy medium in mind.

EH: I go in fear of abstractions, except when they are demanded or earned, and I agree with William Carlos Williams’ notion of “no ideas but in things,” though I’ve never taken as a model his long poem Paterson, where he proves his point repeatedly. It was revolutionary in its “kitchen sink” design, but I also find it sprawling and unfocused. As for humor, I tend to work black humor into the poems. One critic wrote “dark humor suits Hilbert well,” adding “clearly, for all their humor, Hilbert’s poems are not without menace.” I feel that the purely comic poems I attempt are just goofy and insubstantial. Another critic suggests “Hilbert can be humorous, albeit the dark sort.” In my call-and-response poem “Fortunate Ones” from Sixty Sonnets, I have lines that often get a laugh when read aloud: “You can relax now. You’ve been through the worst / (But it consumed your youth, and now you’re old).” It takes a second, but you wait a beat and the laughter is always there. I don’t go for belly laughs, because that’s dangerous. I’m not a comedy writer. That’s a distinct and difficult skill. Still I feel that no author of any kind can capture the whole range of human experience and emotion without including humor of some type.

MD: I get the sense you have specific thoughts on walking the fine line of humor in poetry. This brings to mind a line from your essay, “Wages of Fame: The Case of Billy Collins”; with regards to Collins’ poem “The Introduction” you comment, “Not a bad joke, but not a terribly good poem.” You also call him “the Kenny G. of poetry.” Comes across as a serious slam. You do call attention to what you believe are Collins’ strong points, but much time is spent hammering home that Collins is a one trick pony. Here’s an excerpt from your essay to further this point:

What do all of these poems have in common? A remorseless reliance on free verse leaves each Collins poem to depend on its subject matter alone for support, and his range of subject matter is itself limited to a handful of scenarios. The assumption must be that his topics are so charming that they prove irresistible even in the absence of poetic technique. Whatever else might be said of the tradition of formal technique in poetry, it provides a different means of thinking about the world. A haiku will present a different mental construction than a sonnet, which in turn will be quite remarkably different from a long poem in elaborate stanzas, such as rhyme royal. A digressive, Old Testament-style ramble, as one finds in Walt Whitman, A.R. Ammons, and Allen Ginsberg, will yield different results than one will find in a sestina. By abandoning formal variety in his poetry, Collins has penned himself in. There are limits to what one may say in short, free verse poems.

EH: I’m glad you brought this up. It’s weighed on me for some time. I have nothing personal against Collins. How could I? I’ve never met him, and it’s unlikely I ever will. I’m sure he’s unaware of the essay. Like many poets who write criticism, I was working out my own artistic dilemmas in public. I think the essay stands up after all these years. The excerpt makes it seem as though I’m chastising him for his free verse, which is not the case. I was chastising him for the sameness and lack of variety in his poetry. I have never written in received forms, not even now, and certainly not then. I was thinking about ways to change my poetry, move it forward, really to make it my own, and he became a sounding board. I was writing experimental open form poems—not free verse, because I was not freely using verse technique—and since I had begun writing for musical setting around that time, the notion of composing in rhyme and in measures began to appeal to me. I was challenging my own past and the hundreds of poems I had written in the styles of Allen Ginsberg and John Ashbery.

My examination of Billy Collins really began in 2001, not long after he made the news for having signed a major deal with Random House for what was rumored to be a very large sum of money, some claiming it to be over a million dollars. I wrote an essay called “Mother’s Milk: The Case of Billy Collins” for the Contemporary Poetry Review. It was really a long review of Sailing Alone Around the Room: New and Selected Poems, which had already sold over 22,000 copies in hardcover right out of the gate. I was fascinated by a poet who could cultivate such a large audience. I just couldn’t believe he could sell so many books. I wondered if I could modulate my own writing to achieve similar recognition.

I realized that as lengthy as that first review was, it would not suffice. The editor asked me to get to the heart of the Collins phenomenon, examine the situation and arrive at some conclusions about his success. What did it mean for poetry? What did it mean for other poets? What made him so popular? I decided to dig down and read all of his books, listen to all his recordings, and read reviews of his work in an effort to trace his rise and explain it. This culminated in the longer assessment of his career, “Wages of Fame,” from which you quote above. That appeared four years later and covers his writing up to The Trouble with Poetry, published in 2005. I was led to write the essay after a seemingly random occurrence. I was at a yard sale in my neighborhood in West Philadelphia and came upon a box of Billy Collins books, all of them inscribed to the same recipient, on sale for a quarter a piece, so I bought them all and settled in to read them. What bothered me was that from book to book the poems showed no variation or evolution, no improvement, no experimentation, no shift in style. It may be a misconception that a true artist shifts styles and displays some kind of growth or development, but it would have made for a hell of a more interesting time reading through all his books. He perfected a type of poem right from the start. He’s very good at that type, and he never felt the urge to try something different.

After I published the essay, I found that some readers felt I was too hard on Collins. Others were mystified. They did not understand why I would devote so much attention and energy to poetry they felt was unimportant. Matthew Zapruder wrote to me to say “here’s the thing, there’s nothing wrong with what he does. It’s just fine for what it is.” And he’s right. Maybe no poet’s total works are meant to be read all at once, which is why we have the genus of the selected poems. Perhaps after having unsuccessfully shifted my own style so often, wasting countless hours and years, I was jealous that he had alighted so easily or seemingly easily on something that worked perfectly for him.

Strange as it seems now, at the time I felt I was engaged in a true agon with the older poet. This was bound to happen sooner or later. I had simply turned away from my other influences without much feeling or much of a fight, having quietly outgrown them or become disenchanted. Collins was a new discovery for me. I was probably around 30 at the time, and I had no book, only a handful of magazine publications, but no presence as a poet. I wanted to be forbidding. I wanted to be taken seriously! I wanted to scare people! I wanted to be challenging and difficult. The cheerful, winsome Collins got to me and served as a straw man for my own feelings about poetry. I was feeling my way toward something, a new understanding of the possibilities of my own poetry as well as my own true feelings about poetry of others. I suppose you could say I was developing a sensibility. I used the essay to help shape my taste, decide what was worthwhile and what was not. It’s likely I also felt overwhelmed by deluges of bad or mediocre or unnecessary poetry being written at the time. Those feelings are surely familiar to any poetry reviewer. I am not alone in using the stone of a review to hone my own artistic feelings. After all, T.S. Eliot, Randall Jarrell, and a host of others could be accused of the same.

I still read Billy Collins from time to time. I no longer bridle against what I once perceived as smug, comfortable mediocrity. His poems are what they are, and his audience loves him for them. That’s probably to the good, on balance. A few years ago I went to the Kimmel Center with my sister, who is a librarian and had a spare ticket, to see Billy Collins give an hour-long talk to thousands of people about poetry. His points about modern poetry were perhaps simplistic and dubious, but on the whole I think he was right. Humans like patterns and register variations once a pattern is understood. Too much fragmentation kills meaning. But he’s such an engaging performer that I was able to enjoy time in his company. Surely that’s quite a talent in itself, and it comes across in his poems. I stand by everything I wrote in those essays. I was not deliberately malicious. I would never do anything like that. If anything, I was envious and adrift. Also, I was barely scraping by and unsure of my own abilities as a poet. It’s hardly surprising that someone of low status would feel some resentment toward a poet of success and renown, especially who made his reward seem so effortless. We’ve seen that before, and we’ll see it again.

MD: Your poems, even the less formal ones, are heavy on the music. Still, a number of your poems have been set to music. For instance, “Kite” from Caligulan, just recently. How did this first come about? Why is this appealing? What does it add to the poetry?

EH: Musical setting seems natural to me, given that lyric poems have their origins in song. The first sonnets were sung, and long before then the ancients accompanied themselves on simple instruments while singing poems. I’ve also been fascinated by the tradition of art song, particularly the English tradition running from Dowland and Campion down through Vaughan Williams and Britten, a tradition continued today by Ned Rorem, an American whose body of work contains an astounding number of settings of poetry. I saw him at the Curtis Institute of Music a few years ago when they performed his long poem-song cycle Evidence of Things Not Seen. Remember also that Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony reaches its climax with a choral setting of the poem “Ode to Joy” (“An die Freude”) by Friedrich Schiller.

The music of a poem naturally agitates against its musical setting, which will impose another rhythm and cadence, one which in capable hands will be complementary rather than contradictory. It is a musical art form all its own. When I write arias for an opera I think of them as poems first, but very simple, understandable poems, shorn of the ambiguity and shadings I will put into a poem intended for publication. Christopher LaRosa brought considerable depth of feeling and dramatic tension to my poem, “Kite,” which was further interpreted by the singer and cellist in performance. The commissioning cellist wrote a remarkable essay about LaRosa’s setting of the poem and his techniques for adding significance to the words. There is also the enjoyment and risk of giving your poem to someone who adapts it for another art form, absorbing it and changing it. You are powerless to control the outcome, and that is part of the pleasure. The honor and care that others bestow upon your work is gratifying. LaRosa scored the last part of my spoken word album Elegies & Laments. He scored the four final poems line for line as if producing the score for a film. He is quite gifted and imaginative. I’ve done a few other projects with him, and I hope to continue to work with him for many years to come.

MD: You are about to release a new opera, yes?

EH: My second opera with Stella Sung, called The Book Collector, premiered at the Dayton Opera in May. It was conceived as a companion piece to Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana. Stella came to me with the story already in place. I worked to broaden the characters, give them motivations. This was somewhat difficult with a set of events already in place, not really a plot, per se, but a sequence of events. This happens, then this, and she adamantly refused to change any of that. So I had one hand tied behind my back when writing the libretto, but I feel I did a competent job of expanding the story and making it more plausible. It was an opportunity for me to write in verse much of the time, which is something I did for our previous opera as well. I believe that rhyme and measure work wonderfully with opera. For centuries librettists have screamed in pain as composers wrench their lines out of place, reorder them, remove words.

MD: It sounds like librettos challenge the poet with a host of constraints. I imagine this can get frustrating.

EH: That’s simply part of the collaboration, but much of the verse came through in the end. After one of the performances of The Book Collector, a woman stopped me in the lobby to show me she had copied down her favorite line from the libretto into her program. Someone else asked me to sign his ticket stub. This was the final show, which was a matinee, and moments after taking my bow with Stella, I was rolling my suitcase through the lobby of the Schuster Center to get an Uber to the airport. I now wish I could have stayed and soaked up a bit more of it. Poets are not much accustomed to adulation. The day after the premiere, I went to the Dayton Institute of Art. I wandered into the gift shop, and the woman behind the counters exclaimed, “look, it’s the librettist.” I thought, “I should move here.” Anyway, our premiere, along with Orff’s cantata, topped the box office for the year there, beating out Puccini’s Madama Butterfly. We had 3,700 in the audience. It was a big production, with beautiful 3D digital sets, with motion, combined with physical sets. The singers were in period costumes, since it is set in the early nineteenth century. The ballet sequence was very impressive to me. I know next to nothing about dance. Of course the orchestra and singers were wonderful.

It’s fun, as a poet, to be involved in a big collaborative production. Auden, who wrote operas with Stravinsky and Britten, remarked that it’s one of the few times a poet can join in the communal art work, something involving many performers, performed for many people. Poetry can be a lonely calling. Working in opera helps to alleviate that. Poets don’t usually get to take bows before thousands during a standing ovation. We hope to see it performed again in the future in other cities, along with our first opera together, The Red Silk Thread: An Epic Tale of Marco Polo, which I had much more of a hand in crafting from the start and which I feel is the superior opera of the two.

MD: You dodged my question about having an affinity for swords. And I know it’s true because I’ve seen a video of you opening a champagne bottle with some sort of sabre. Let’s address this and then we can move on and discuss your interest in pirates, which happens to be the title of a terrific poem of yours from AoYotGE (though boasts a less inventive title than those in Caligulan, which include such gems as: “Queen of the Demonweb Pits,” “Hotel Water Deemed Safe Despite Corpse,” “Sir Fish and the Bridge to Nowhere,” “Your Heroes Left You For Dead,” “Ice Dwellers Watching the Invaders”).

EH: Yes, what you saw is called sabrage. It is a technique that uses the blunt side of the blade. If you find the seam on the bottle, which can be almost undetectable on finer labels, you align your sword along the seam to strike the collar. The top blazes right off with no shattering. It was first used by Napoleon’s Hussars, his light cavalry. There are stories of officers opening bottles this way to impress Madame Clicquot in her vineyard. The rationale is simple. In victory you feel you deserve it. In defeat, you need it. We sometimes perform it in order to celebrate a visit by a friend, a big welcome!

The swords I keep in my office at home and my desk at work are affectations. I bought a few at auction when I was working on the libretto for the first opera I wrote with Stella Sung. I needed a scene that would really force a climactic decision on the part of the central character while also emphasizing his arrogance. While aboard the emperor’s imperial junk, Marco Polo chooses to ignore warnings about the possibility of attack by Wokou, Japanese pirates. When the inevitable attack comes, he has to decide if he will take on insurmountable odds in order to save the woman he has just renounced, and he has to do it in a moment when no deliberation is possible, only a gut reaction, as we call it. Anyway, I knew that a big opera would have space and resources for a battle, and I sense that the actors and supernumeraries really enjoyed working with the fight coordinator to bring it to life with swords and bo staffs. I whirled around the lobby here at work with swords while working out the mechanics of the scene. It’s all ridiculous.

As for the titles of the poems in the collection, I feel I should say a few words. “Pirates” is, of course, used sardonically in that poem to describe the family on the block that refuses to conform to suburban norms, allowing grass to grow long and failing to weed the yard, thus raising the “black flag.” All of the other titles you mention, save one, are appropriated. “Queen of the Demonweb Pits” is the name of the final module of the long, glorious Dungeons and Dragons series beginning with Against the Giants, G1-3, followed by Descent into the Depths of the Earth, D1-3. This expedition culminates in an interdimensional confrontation with a queen demon, Queen of the Demonweb Pits, designated Q1, set on one of the 666 levels of the abyss. I had been rereading the modules while drunk, and I felt that title perfectly suited the dark, twitchy quality of that poem, which is about drugs. I read the modules as a highly technical variety of fantastic literature, just as I read Robert E. Howard’s Conan sagas. It’s like reading the blueprint of a story rather than the story itself.

“Hotel Water Deemed Safe Despite Corpse” was ripped from the headlines, as they say. There’s an elevator security video from a Los Angeles hotel of a young woman behaving erratically, seeming to hide on an elevator, peeking outside of it, getting off and then running back on, as if she is being stalked, but there is no sign of anyone else in the video. After many excruciating minutes of this, she finally allows the doors to close. The next day, her body was found in the rooftop water tank, though her body seemed too big to actually be put into it. I was haunted by this, and the crime is apparently unsolved. For all I know it’s an urban legend. Again, I felt it really gets the feel of the poem down. That poem is also about free-floating dread and a sense of impending doom.

“Sir Fish and the Bridge to Nowhere” is more playful. Sir Fish is the name of a Chesapeake two-seat wooden kayak my wife and I use to ply the waters of the Atlantic coast. We borrowed the Vietnamese term for the whale shark, “ca-ong.” The Bridge to Nowhere is real. It appears in the Weird New Jersey book. If you follow the instructions, you will find a gravel road that leads off into a marshland at the New Jersey shore. It is unmarked. If you take it and follow it to its end, you come to a bridge that seems to lead nowhere. It’s creepy. It starts and goes out over the waters of the bay into the marshland and then stops. It was built by a telephone company at one point to allow engineers to get to the poles that lead over the marsh before going under the waters of the bay to the barrier islands. There is also a “Lonesome Grave of Mud Island” out there somewhere, though we haven’t yet managed to find it. The story in the poem is about a time when Lynn and I were lost in the marshes, which can become increasingly terrifying as the sun sinks toward the horizon. To be trapped out in the marshes after dark would be a disaster. We were incredibly relieved to make it back before sundown.

“Your Heroes Left You for Dead” is also invented, though it’s an approximation of a line from a song, misheard in this case. Or approximated, really. Misremembered. The line is simply “heroes left you to die” in the song “Supercrush!” by Devin Townsend. Good lines stay in my head and just float up when I need them. Finally, “Ice Dwellers Watching the Invaders” is an 1879 painting by William Bradford. When I wrote that poem I was spending my mornings with a cup of coffee looking at paintings in a big book of American art. I was taken by the beauty and danger of the moment in the painting, also the historical moment it depicted, so that poem is really an example of ekphrasis more than anything else.

MD: How do you feel about Caligulan winning the 2017 Poets’ Prize?

EH: I find myself unequal to the task of properly expressing my gratitude for the recognition, to be honest. I’ve written and published poetry for nearly thirty years, and this is the first public acknowledgment I’ve received. It’s a great distinction to receive a prize that’s gone to the likes of Miller Williams, Marilyn Hacker, Maxine Kumin, Adrienne Rich, and Marilyn Nelson in the past. It’s also a distinct honor to be given a prize by a committee of fellow poets. I believe the Poets’ Prize may be unique in that regard.

It certainly came as a surprise. I was reading at the Pen & Pencil Club, in Philadelphia, the evening I found out from my publisher that the book was nominated, and when the audience kindly applauded at the news I jokingly remarked that it was just one more thing for me to worry about. I never thought Caligulan would be a finalist much less the winner, particularly among such strong contenders. One of the two other finalists was Donald Hall’s Selected Poems, published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. I reviewed the book for the Hopkins Review last year and found it a powerful distillation of his life’s work. It’s his third selected poems overall, a slim volume, much smaller than the larger ones that preceded it, a definitive selection of what he has come to feel are his strongest poems. I’ve interviewed Hall and corresponded with him for years. He’s the last person I still post paper letters to. The other finalist was Shakespeare’s Horse, by Joseph Harrison, published by the renowned Waywiser Press, which has issued some of the best books of new poetry we’ve had the past decade. I had the honor of appearing in the Swallow Anthology of New American Poets with Harrison a few years ago. In fact, according to the felicity of our surnames, he appears directly before me in the book. I hope to see them both at the Nicholas Roerich Museum in New York City for the ceremony, though I don’t know if Hall is traveling as much these days.

MD: What is on the horizon?

EH: My writing life has slowed enormously since the birth of my son, Ian, in December 2015. He’s a miracle, and he’s made me very happy. But it’s also a miracle if I find half an hour to write in the course of a week. Though, really, it hardly matters anymore. Poetry and feelings about poetry are constantly turning over in my mind, night and day, and all I usually need is a minute here or there to write poems down, transpose them from pure mental and aural energy into a written record that can be shared. What I miss most is the time and leisure to revise at length. I spent a year revisiting and refining the poems in Caligulan, and I’d like to figure out a way to do that for my next book, Last One Out, which will appear in 2018. I’m also working on a book beyond that one, tentatively titled Visitations. I’ve taken down a few notes for an opera libretto I’d like to write set in Shanghai in the years immediately following the Second World War, but my wife insists I not enter into any serious operatic work while Ian is so young, because the process of collaborating on such a large work of art with a composer is sometimes frustrating, and very time-consuming, if often exhilarating. I have been writing essays as well. I’ve recently published one about first editions of famous books of poetry, showing how small the print runs were for even the most important ones, how often they were self-published or posthumously published, and how often they were met with bafflement by readers and critics. I have another essay, which will appear in May, about literary relics and artifacts, Hemingway’s typewriter, Virginia Woolf’s standing desk, Shelley’s heart, Evelyn Waugh’s ear horn. I may be giving a talk based on it at the Rosenbach Museum and Library. I’m also working away on an essay about my experience in a mosh pit at a Slayer concert at the venerable age of 46, called “Poetry of the Slayer Pit.” Finally, I’m working on what’s turned out to be a very long essay about Robert Lowell’s blank-verse sonnets for Literary Matters, the online magazine of the Association of Literary Scholars, Critics, and Writers. In addition to my day job as a rare book dealer, where among other things I am helping a collector to build a large collection of first edition books of poetry from the Romantic Era to the early twentieth century, I teach at a low residency master of fine arts program based in Colorado. Just now I’m finishing up a course on the historical foundations of English prosody. For the open topic paper, I was delighted to find that the students chose topics important to me and to my own poetry, German tonic verse, eddic verse, skaldic verse, uses of hendings, Baltic verse and zeugma. One created an extraordinary syntax tree to explain why the stanzaic units in one of Robinson Jeffers’ poems should be understood as couplets rather than quatrains. I get to talk about technique, theory, practice, and, most importantly, the art of being an artist in America today, handing on the tradition that’s been kept alive since the dawn of history, not allowing it to be snuffed out, passing it along, that’s maybe the most important thing of all, and I hope to be able to do it for a long time.

No Comments