I should be comfortable among the headstones

Of Tennessee, for I am a Southerner,

Father advised, before I fled to Philadelphia,

And, unlike the Northerners, disinclined

To say ‘no,’ to folks, or take the hard view,

But, as my mother asked my second wife,

Why does he keep marrying these Yankees?

Such are the bona fides that orientate me

In this neatly kept up, alternative Wasteland,

Just down the road from Barbeque Joe’s

And the flea market where bikinis on a line

Are decorated with the Stars and Bars.

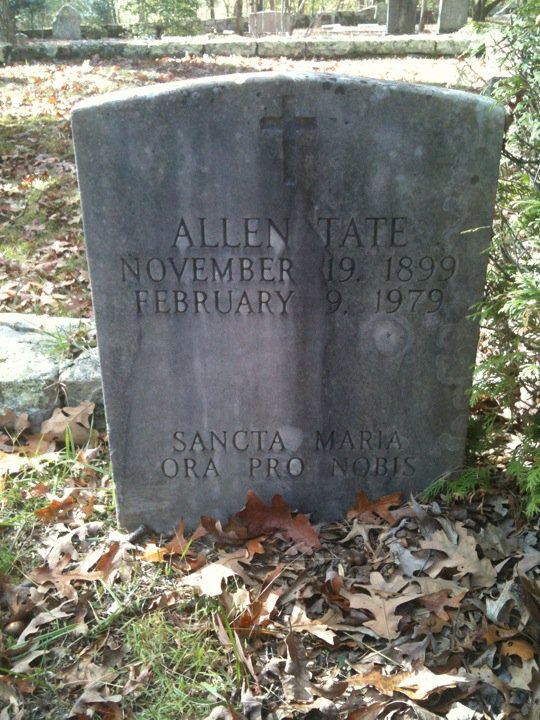

Allen Tate is said to lie among these ranks.

Though I stand upon an infant’s grave and peer

Around the oaks and through the gates,

Chained back (for all may enter here),

Nothing marks him from my elevation.

Instead, my eye falls on the slim women

Who loiter on the porch of Stirling’s

Across the street. Labels on their shirts

Display their assumed creative identities

Of Poetry, Fiction and Playwriting.

They seem posed like Pierian figures,

And yet their purpose here is not to grant,

But to possess their own inspiration.

They have the look of those stern angels

Tate described as turning men to stone.

They defer a glance at me, a stiff voyeur,

While I scuffle for some official slate

That might help me recognize a buried poet.

I’m gray and leaning like these markers

That celebrate a final confederacy

And concerned, somewhat, that snakes,

Copperheads and rattlers, might take

My fascination with the young women

As a chance to strike, but nothing moves.

No one would make me out as a living actor

Set back among this broken marble,

As I take in monuments, unlettered

By a century of industrial weather,

In this necropolis of the academy.

Granite provides for Sewanee’s local color.

Yesterday, as I passed a traffic circle,

I was surprised by a layer cake memorial

to Bishop Leonidas Polk, Sewanee’s founder.

A childhood of education in the Lost Cause

enabled me to recognize him as a commander

of an infantry corps in Braxton Bragg’s army.

Once, I thrilled to read of Chickamauga.

Now, the stars slashed on flags along the rows

Summon for me the images of Dobermans

Set loose, of fire hoses that the sheriffs played

On singing marchers and of churches bombed.

Good Soldier Lee equals Good Soldier Rommel.

History has lectured enough on that equation.

Though no one is so impolitic at our conference

To discourse on blood, or race, I mention Polk.

Someone nods, then goes on to discuss

The problem of getting a second book published.

In classes, a few old names are turned over.

A poet from New York writes on Audubon.

Have you read Warren, I ask her. “Not really.”

Here, the craft of poetry is all business.

Tate, your oblique diction might be dismissed

In the writers’ workshops where tropes

Are as interchangeble as the musket parts

Colt milled. Better to offer civil criticism

than confront the ravenous grave of the South.

I leave the dead and cross to Stirling’s,

So much the image of the Victorian

Farmhouse that my mind puts up Brady’s

Photographs of lounging officers on porches.

Steam rises from the stout German boilers.

The muses have departed for their classes.

Tate, should I mine-sweep for your honors,

Interred among these generations of rage,

Or read your lines at midnight by your grave?

The students do their talking at the parties.

No one from town will claim the body

And those left here were silent all their lives.

Time coils around the stones and rattles,

Though the sound is neither ode nor elegy.

No Comments