So this is your lot.

After the years you spent

filling your house

with items discarded or bought

at ridiculously low prices,

knowing someday

someone would walk in willing to pay

more than you,

plain and simple,

the fire marshal or whomever the island’s citizenry

appointed to such duties as this

has declared your house

unfit for public perusal.

And your response,

to your neighbors’ horror,

was to move everything outside,

right in front of the main thoroughfare

in full view of passing tourists.

We’ve bicycled the circumference

of this entire island

as tourists are wont to do

and you haven’t moved an inch

unless it was to turn the page of your newspaper

(not today’s, by the way)

and yet when we stop to talk,

your generosity is as suited

to this island as the round smooth stones

washed ashore and by chance of nature

balanced one atop the other.

You start telling us of your miraculous finds,

croaking in a way that suggests

you haven’t spoken much today

or yesterday, except to ineffectively scold the kittens

who wander away from their own pile

of newspapers like loose and furry

tentacles over the rubble. Their thin high voices

nearly opposite from yours,

lost in the white caps’ crash

against the narrow beach, mostly pebbles.

We’ve come here to get away

and see the monarchs’ migration,

but you stay here year ‘round,

even when provisions come in just once a week,

and the jagged ice spreads out from the island

like a cape of iron slag.

—Most like an island then, I suspect.

Even now, high above the tallest trees

in twos and threes, the deliberate

orange butterflies, all compass and clock,

rest and gather and move on, away from here.

And we, straddling for balance, go right on cycling.

The poems of Compass and Clock take their inspiration from the intersection of the natural world and the human, exploring the landscapes in which those intersections occur. Those landscapes range from David Sanders’s native midwestern countryside to the caves of Lascaux and an enchanted lake where relics of lost lives are washed ashore. Yet, the true source of the poems’ vitality is Sanders’s attention to the missed or misread moments, those times when the act fails, and the perceived clashes with the actual.

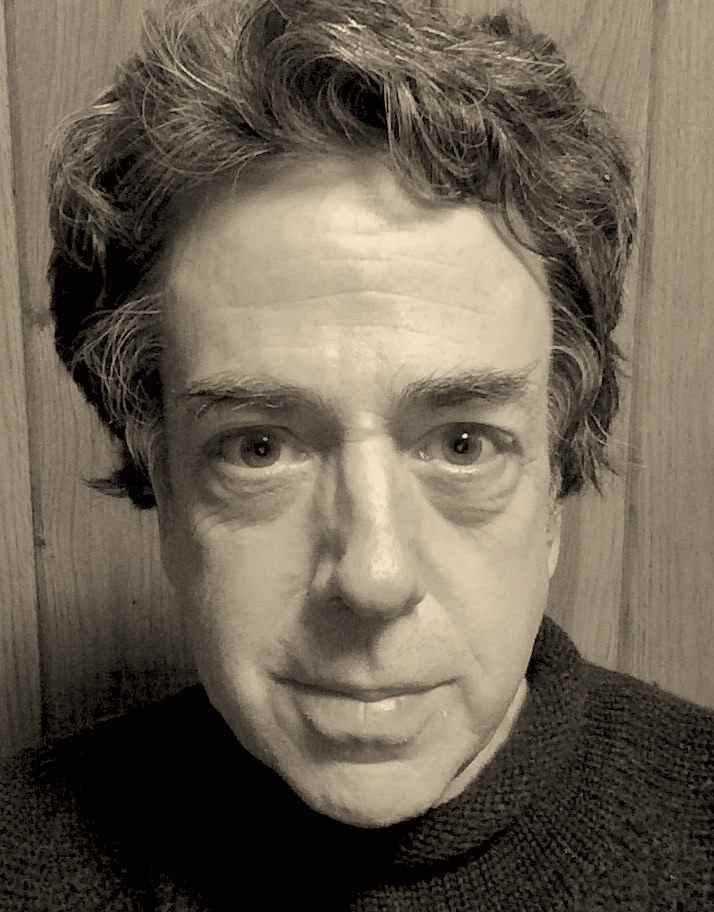

Here, the satisfying pairing of elegance and vulnerability invites the reader to tour those uncanny landscapes from which one returns irrevocably changed?—?refreshed, but wistful. In a review of his earlier limited-edition work, Time in Transit, the Hudson Review called David Sanders “a poet to watch.” With the Swallow Press publication of Compass and Clock

, we have the realization of that promise.