My farewell to American poet Donald Hall appears in the Notes & Comments section at the end of the most recent issue of The New Criterion. It was a distinct honor to have been asked.

When Donald Hall died in June, we lost one of the last members of a remarkable post-war cohort of poets that Hall himself did much to define and promote, and among whom he stood as a major figure. Born in 1928, Hall came of age in the long shadow cast by modernist titans such as T. S. Eliot and W. B. Yeats. Like the rest of his generation, Hall was compelled to discover or rediscover methods that would allow him to write poetry that struck readers as new while remaining sturdy for posterity. In books of moving and amusing verse, Hall sustained the stylistic legacies of poets such as Frost and Hardy while devilishly mingling doses of Whitman and others. Though foremost a poet, Hall worked as a professional writer, sometimes publishing three books in a year to make the mortgage. He wrote children’s books, collections of essays, and innumerable reviews. He wrote about baseball for Sports Illustrated and fatherhood for Playboy. His elegiac poems are taught at prominent medical schools. He appeared in Ken Burns’s documentary on baseball and voiced Walt Whitman for The Civil War. He also published memoirs that conjured a lost age—milk delivered to porches from horse-drawn wagons, spirited boys dressed in knickers, lazy summer afternoons watching Lon Chaney, Jr. in Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein. Part of Hall’s perennial appeal lies in his ability to share stories of his childhood and his family’s lore in a charming and poignant style. Like any gifted storyteller, he proved capable of telling some tales more than once with little loss of interest for the reader.

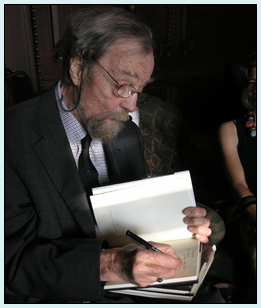

In his celebrated essay “Poetry and Ambition,” Hall explained that when striving to create durable poems, poets are “certain of two things: that in all likelihood we will fail, and, if we succeed, we may never know it.” His tireless ambition resulted in memorable poems of the natural world, the contours of family life, the joys of love and sex, and, perhaps most compellingly, the pains of irremediable loss. Though always determined to succeed, Hall knew to avoid the kind of ambition that proves baleful. In a 1991 Paris Review interview—accompanied by a photograph of a full-bearded Hall tilting back to pitch a baseball—he relates a story about playing softball with Robert Frost in 1945, when that particular titan was seventy-one years old: “He fought hard for his team to win and he was willing to change the rules. He had to win at everything. Including poetry.” Hall learned a lesson and handled his own career more graciously.

No Comments