“OUR FEAR OF THE UNKNOWN—OF THOSE THINGS THAT GO BUMP IN THE NIGHT—IS AS OLD AS TIME ITSELF”

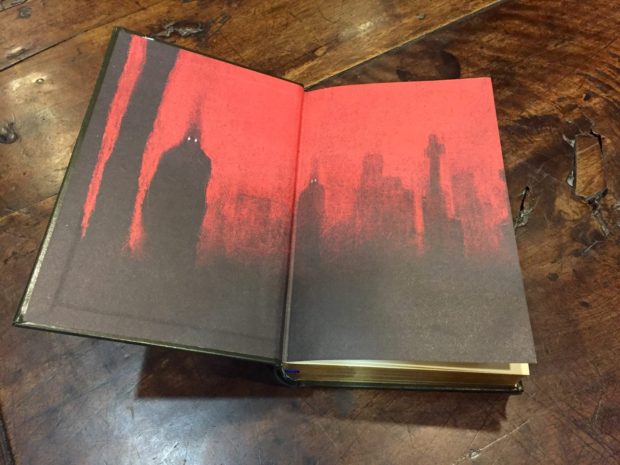

(ERNEST HILBERT) LOVECRAFT, H.P., Franz Kafka, Edith Wharton, et al. Classic Tales of Horror. San Diego: Baker and Taylor/Canterbury Classics, 2015. Stout octavo, hardcover, pictorial boards. $24.95. ISBN-10: 1626864659

Purchase from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

Ernest Hilbert provides a comprehensive introduction to this new popular edition of the classic horror stories, spanning the century between Polydori’s groundbreaking 1819 short novel Vampyre and early twentieth-century classics by H.P. Lovecraft and Franz Kafka.

* * *

Introduction by Ernest Hilbert

We’ve all felt the rush of fear in the dead of night when we wake with a fright, chilled to the bone, feeling we are not alone. Our fear of the unknown—of those things that go bump in the night—is as old as time itself. Such primordial terrors take hold in the small hours, when the world sleeps, but they are captured, like genies in bottles, by the authors you will encounter in Classic Tales of Horror—authors who, above all, remind us that all is not always well, that we are not always safe, nor do we fully understand the universe as much as we believe we do. In his pivotal essay “Supernatural Horror in Literature,” H. P. Lovecraft, one of the undisputed masters of the genre, began by affirming quite simply that “the oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown.” It is hard to improve on this. A menace known, seen, and understood can never be as frightening as one that remains hidden, lurking in the shadows. This is the timeless element of these stories, and it contributes to their enduring appeal. They are as engaging today as they were when they first appeared.

Stephen King, one of the most successful horror writers of all time, knows this and suggests that in horror fiction “we often experience that low sense of anxiety which we call ‘the creeps.’ ” He touches on an important point, which is that the fear of the unknown comes not only from outside phenomena but also, much more unsettlingly, sometimes from within. A recurring theme in these stories is the skeptic’s struggle to retain his faith in reason—to reassure himself that he is sane and that weird phenomena can be explained away—in the face of mounting evidence to the contrary. Even if he comes to accept the evidence as real, he may find himself unwilling or unable to talk about it with others. As Charles Dickens wrote in “The Trial for Murder”: “I have always noticed a prevalent want of courage, even among persons of superior intelligence and culture, as to imparting their own psychological experiences when those have been of a strange sort.” The terror arises, in part, from a character’s inability to be certain that what he experiences with his five senses is, in fact, real, that some presentiment or “feeling” is actually attached to a supernatural event. The horror story, from its genesis, has always relied on a strong psychological element: Ancient, primitive forces somehow persist into the present day; subterranean energies force their way to the surface; tragedies unfolded long ago are reenacted. Characters wrestle with their own psyches in a vain effort to cling to remnants of sanity.

Origins of the Genre

In 1773 John Aikin and his sister Anna Laetitia Aikin wrote an essay called “On the Pleasure Derived from Objects of Terror,” in which they posed that “the apparent delight with which we dwell upon objects of pure terror, where our moral feelings are not in the least concerned, and no passion seems to be excited but the depressing one of fear, is a paradox of the heart.” Indeed, it is very hard to understand the attraction. Why would we want to be frightened? Perhaps that is the most frightening aspect of the stories. They describe occurrences outside the natural run of events, beyond what seems possible to a scientific mind, and as such, they can be dismissed as absurd, yet we return to the old places, push open the creaky doors, and enter because we are searching for something we have lost, or been denied, by our calculating, rational modern society. We can agree that most horror stories share certain features, but they also tend to separate themselves into recognizable categories (even if these sometimes combine to make hybrid forms, as we will see). The most common category in this collection is the ghost story, the old standby, which can be further subdivided into a variety of haunted-house tales and other records of hauntings. The closest contender to the ghost story is the vampire story, which also assumes diverse forms, beginning with John William Polidori’s groundbreaking story “The Vampyre.” These are followed in frequency by the straightforward monster tale, along with stories concerning demonic activity, deals with the devil, and terrible animals large and small. Perhaps rarest of all is the work of pure psychological terror, as one finds with Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s “The Yellow Wallpaper” and Franz Kafka’s profoundly unsettling and highly suggestive stories, whose inhospitable visions of alienation and oppression mark him as one of the most important authors of the twentieth century.

So, we must ask, what do we call these stories? There is no easy answer, as they go by many names and arrive in many guises: horror stories, Gothic novels, dark fantasies, weird tales, works of mystery and imagination, reports of the grotesque, and chronicles of the uncanny, bizarre, and supernatural. Some prefer the dignifying designation of “spectral literature.” Even fairy tales, such as those recorded by the Brothers Grimm, are at times calculated to worry us. There is no way to know the deepest origins of these stories, though they have haunted us for centuries in old wives’ tales and warnings to children, and even deeper in legends and ancient myths. There is much to terrify the attentive reader of Homer’s Odyssey (800 bc), with its cannibals, witches, and monsters (on land and in the sea), as well as its hero’s descent into the underworld to spill ritual blood and commune with the restless dead. Even earlier, the Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh (circa 2000 bc) depicts a battle between its hero and the monstrous giant Humbaba. In fact, Lovecraft insists that because the horror tale deals directly with primal emotion, it “is as old as human thought and speech themselves.” We would do well to call them tales of horror—because that is, in fact, what the best of them actually do: place us in a state of horror.

Efforts have been made to explain the enduring appeal of the horror story in its many forms. Edith Birkhead, in her 1921 study The Tale of Terror, investigated medieval stories handed down by oral tradition set “in an atmosphere of supernatural wonder and enchantment.” She points to the presence of horror in Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur (1485), Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene (1590), Christopher Marlowe’s The Tragical History of the Life and Death of Doctor Faustus (1604), and John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress (1678). The first great outpouring of these stories in a purer form occurred in the era of Gothic literature, which spans roughly from 1764, with Horace Walpole’s novel The Castle of Otranto, through 1820, which saw the publication of Charles Maturin’s novel Melmoth the Wanderer, though, as we will see, the influence of Gothic storytelling continues to linger to the present day.

Though bloodcurdling stories have been told around fires—in prehistoric caves and Victorian drawing rooms—from time immemorial, the modern horror story really begins with Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto, set in a labyrinthine Italian castle. It was followed by many imitators, including Ann Radcliffe’s 1794 novel The Mysteries of Udolpho, which some believe to be the archetypal Gothic novel. Walpole’s wildly popular novel (originally published under a pseudonym, though he took credit in subsequent printings) initiated the vogue for stories set on the Italian peninsula, in old ruins or abandoned villas, as we observe with Lovecraft’s fable “The Tree” (set in the classical period), Ambrose Bierce’s graveyard story “An Inhabitant of Carcosa,” Nathaniel Hawthorne’s “Rappaccini’s Daughter,” and Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Masque of the Red Death” and “The Cask of Amontillado.” Walpole’s book also introduced the technique of framing a story through documentation, offering it as if it had been lately found as an historical account, a collection of diary entries, or courtroom records, often alleged to be translated from a foreign language. This was the eighteenth-century equivalent of the “found footage” horror film popularized by The Blair Witch Project and used with great effect in the Paranormal Activity movies. It lends an air of credibility and antiquity—sometimes immediacy—to the stories while also making them appear more exotic.

Further, Walpole established not only the atmosphere but the location. In his 1927 book The Haunted Castle, Eino Railo explained that the castle so common to these stories had an essential “collection of family portraits” along with subterranean vaults and passages, hidden triggers for “a secret trap door.” Indeed, one will encounter many castles, ancestral homes, manors, mansions, villas, and more modest haunted houses in these pages. Haunted houses and other evil places never seem to lose their allure. Fully half of the stories, if not more, occur in such gloomy quarters. The houses in this book laid the foundation stones for later infamous addresses, such as those in Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House (1959), Richard Matheson’s Hell House (1971), Stephen King’s The Shining (1977), and Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves (2000).

Spooky Places

Ghosts and hauntings abound in these stories, usually associated with a particular place—a tomb, a graveyard, or, as we have seen, a haunted building. The Gothic novel, with its trappings of desolate castles and stormy nights, eventually gave way to what we call the ghost story, a child of the Victorian era. Dorothy Scarborough noted in her 1917 study The Supernatural in Modern English Fiction that “the ghost is the most enduring figure in supernatural fiction. He is absolutely indestructible . . . he appears as unapologetically at home in twentieth century fiction as in classical mythology, Christian hagiology, medieval legend, or Gothic romance,” adding that “he changes with the styles in fiction but he never goes out of fashion.” Ghosts linger, sometimes for generations, reliving their misfortunes, seeking revenge, or desperately trying to warn unwary visitors.

Algernon Blackwood begins “The Empty House” by asserting quite bluntly that “certain houses, like certain persons, manage somehow to proclaim at once their character for evil. In the case of the latter, no particular feature need betray them; they may boast an open countenance and an ingenuous smile; and yet a little of their company leaves the unalterable conviction that there is something radically amiss with their being: that they are evil.” One can’t help but notice how many stories include the word “house” in their titles: “The Shunned House,” “The Empty House,” “The Judge’s House.” We must begin, however, with the most famous of houses, Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher,” a story of a crumbling edifice haunted by its still-living inhabitants, a frantically nervous man and his sickly sister, the two remaining heirs of a declining and degenerate family line. Horror stories of real significance begin with Poe, who is the true father of the American horror story, though his achievements are by no means limited to horror stories. He is credited with creating the detective story in 1841 with “The Murders in the Rue Morgue.” He also dabbled in science fiction (“Ms. Found in a Bottle,” 1833), published significant works of literary criticism, and was celebrated as a poet.

It is worth considering the opening passage of “The Fall of the House of Usher,” as it is perhaps the finest description of its kind. As our narrator approaches the eponymous house, having been mysteriously summoned for a visit by a childhood friend, Poe combines several elements to achieve his effect, incorporating bleak weather, keenly felt emotion, and observation of desolate surroundings and physical decay to conjure “an utter depression of soul.” This promises to be one truly ominous visit.

During the whole of a dull, dark, and soundless day in the autumn of the year, when the clouds hung oppressively low in the heavens, I had been passing alone, on horseback, through a singularly dreary tract of country; and at length found myself, as the shades of the evening drew on, within view of the melancholy House of Usher. I know not how it was—but, with the first glimpse of the building, a sense of insufferable gloom pervaded my spirit. I say insufferable; for the feeling was unrelieved by any of that half-pleasurable, because poetic, sentiment, with which the mind usually receives even the sternest natural images of the desolate or terrible. I looked upon the scene before me—upon the mere house, and the simple landscape features of the domain—upon the bleak walls—upon the vacant eye-like windows—upon a few rank sedges—and upon a few white trunks of decayed trees—with an utter depression of soul which I can compare to no earthly sensation more properly than to the after-dream of the reveller upon opium—the bitter lapse into everyday life—the hideous dropping off of the veil. There was an iciness, a sinking, a sickening of the heart—an unredeemed dreariness of thought which no goading of the imagination could torture into aught of the sublime.

At times such landscapes seem like nothing so much as the outward manifestation of what would have been called a state of melancholy, that “utter depression of soul,” what today—in an age more clinical and more cynical—might be termed major depression.

Though Poe’s House of Usher may be the best of its kind, Bram Stoker, author of Dracula, invents a similarly terrible locale in “The Judge’s House,” where a young student seeks seclusion so that he may study undisturbed. He waves away the vague warnings of the locals, insisting that his studies in mathematics will give him “too much to think of to be disturbed by any of these mysterious ‘somethings’ . . . his work is of too exact and prosaic a kind to allow of his having any corner in his mind for mysteries of any kind.” Likewise, his hired help, the sturdy Mrs. Dempster, sniffs “in a superior manner” and explains “bogies is all kinds and sorts of things—except bogies! Rats and mice, and beetles; and creaky doors, and loose slates, and broken panes, and stiff drawer handles, that stay out when you pull them and then fall down in the middle of the night.” The rats in question—and a very large, tenacious one in particular— begin to make him think that he might have placed himself into a worrying situation well out of reach of help.

Henry James—one of the indisputably major authors in this book—indulged his darker side with the novella The Turn of the Screw, which stands out as one of the great American ghost stories, lending itself to adaptation not only to film but also as a highly regarded opera by Benjamin Britten with a libretto by Myfanwy Piper. The story of a callow governess, sent to keep watch over two troubled, orphaned children in an isolated mansion, unfolds with immense subtlety. James carefully captures that “hush in which something gathers or crouches.” His heroine, who may or may not be mad herself, who may or may not be hallucinating the figures she sees in the windows at night and on dark staircases, is altogether unsure herself, exclaiming “No, no—there are depths, depths! The more I go over it the more I see in it, and the more I see in it the more I fear. I don’t know what I don’t see, what I don’t fear!” James is the most indirect and refined of the authors in this collection, and his prose is exquisite. He works through suggestion and misdirection, hints and queries. “Sir Edmund Orme” is no less unsettling, though much of it is set out in broad daylight and in public. Imagine if you could see an apparition that no one else—save a single other person—could see. You would be thought mad if you so much as mentioned it. This is the terror that confronts the narrator of James’s story, in the form of a personal testament found in papers of the author and presented by the executor: “I had heard all my days of apparitions, but it was a different thing to have seen one and to know that I should in all probability see it familiarly, as it were, again.”

Edith Wharton, also a major American novelist, known for The House of Mirth and The Age of Innocence, composed many ghost stories. “Kerfol”—the name of an abandoned French estate, “the most romantic house in Brittany”—reminds us that not all ghosts appear in human form. A brutal mauling death is attributed to another kind of ghost, of the four-legged variety, proving that man’s best friend is sometimes his greatest nemesis. In “Afterward,” a wealthy American couple inquires hopefully about ghosts in an old English house called Lyng, which they intend to rent in Dorsetshire. As one often sees in these stories, they are told they “can get it for a song” (the observant reader will notice that Kerfol was also going for “a song”). They are tantalizingly informed by a friend who arranges the rental: “Oh, there is one, of course, but you’ll never know it.” They move into the shadowy old manor in hopes of luring out its resident ghost. Disappointed, they settle into a comfortable routine—she gardens, he works on his book—only to discover that they may have brought their own ghost with them from far away.

A Ghost of a Different Color

While the ghosts of James and Wharton are elusive and thin as air, F. Marion Crawford’s ghosts are relentless and direct. “The Screaming Skull” begins with its narrator explaining, apologetically and somewhat defensively, “I have often heard it scream. No, I am not nervous, I am not imaginative, and I never believed in ghosts, unless that thing is one. Whatever it is, it hates me almost as much as it hated Luke Pratt, and it screams at me.” We listen patiently as he continues in this vein, attempting to justify and rationalize his decision to live alone with the apparition. Despite his best efforts, he grows increasingly terrified and uncertain of himself as his tale progresses. He repeatedly offers us another glass of whiskey—“You may as well finish that glass while I’m getting it, for I don’t mean to let you off with less than three before you go to bed.” A stiff drink helps, but it’s not enough, especially when he moves to retrieve the skull from its box to find it has gone off wandering on its own. Crawford’s 1911 contribution to the vampire genre, “For the Blood Is the Life,” is also, largely, a ghost story. It treats traditional themes of unrequited love, unpunished crimes, and young death with a very modern sensibility. His vampire is an innocent young woman, trying to remember what it meant to be alive by slowly feeding upon the man she once loved from a distance, draining her lover of the very life she hopes to regain.

Charles Dickens was an aficionado and a virtuoso of the ghost story. We should not forget that one of his most beloved stories, A Christmas Carol, is, in fact, a ghost story. Perhaps, because it is also a story of redemption, rather than ruin, it remains more popular than his other ghost stories, such as “The Trial for Murder,” in which Dickens gets right at the heart of the revenge story. During the trial, the accused is seen pointing at someone he sees sitting with the jurors, who begin to wonder how many are in the box with them after all.

“Why,” says he, suddenly, “we are thirt—; but no, it’s not possible. No. We are twelve.”

According to my counting that day, we were always right in detail, but in the gross we were always one too many.

There was no appearance—no figure—to account for it; but I had now an inward foreshadowing of the figure that was surely coming.

In Dickens’s most frightening ghost story, “The Signal-Man,” the narrator meets a lonely signal-man, posted to a cold, remote railway embankment, who tells him, “I am troubled, sir, I am troubled.” The narrator, concerned, presses him for details and learns that the signal-man nightly experiences terrible forebodings of an accident. He understands that he is being warned by spectral figures who wave and shout, but he cannot see their faces or figure out what it is he is being warned about—until it is too late.

Haunted houses have many rooms. E. F. Benson’s “The Room in the Tower” ingeniously combines a story of foreboding dreams, a haunted room at the top of an old tower, and life-drinking vampires in a single chilling tale. Benson learned from the best. He was close friends with the distinguished writer M. R. James. Benson was present at a meeting of the Chitchat Society at Cambridge University when James read his first two ghost stories, “Canon Alberic’s Scrap-book” and “Lost Hearts,” in October 1893 (both are included in this volume). The literary influence was immediate and profound. Benson went on to write more than fifty classic ghost stories, and his 1912 story “The Room in the Tower” remains his signature work.

H.P. Lovecraft is second only to Poe among American horror writers. Like Poe, he died prematurely (Poe at forty, Lovecraft at forty-six), but he left behind a vast assortment of stories and novellas mapping out his own invented pantheon of ancient terrible gods and other beings, known collectively as the Cthulhu Mythos, after his most famous deity. In his story “The Shunned House,” Lovecraft, always innovative, deepens the horror of the traditional haunted house. Locals recoil from the house in question, and the owners find themselves unable to rent it for long.

The general fact is, that the house was never regarded by the solid part of the community as in any real sense “haunted.” There were no widespread tales of rattling chains, cold currents of air, extinguished lights, or faces at the window. Extremists sometimes said the house was “unlucky,” but that is as far as even they went. What was really beyond dispute is that a frightful proportion of persons died there; or more accurately, had died there, since after some peculiar happenings over sixty years ago the building had become deserted through the sheer impossibility of renting it.

The narrator sets out with his scientifically minded uncle to move into the basement of the house and learn its secrets. They begin digging into the basement floor and discover an evil far stranger than they had ever imagined.

Prolific French novelist Honoré de Balzac is celebrated for his massive collection of interlinked stories about French life in the first half of the nineteenth century. It is known collectively as La Comédie humaine, and it contains its share of ghost stories. In “La Grande Bretèche,” the narrator finds himself captivated by a derelict mansion that seems to have been suddenly abandoned. He returns nightly to gaze up at the dilapidated facade in wonder. After meeting the estate’s executor in a local café, he hears a perverse tale of betrayal and revenge, in which the lord of the house walls up a man alive. In Guy de Maupassant’s “A Ghost,” we find a single haunted room in an old manor and its occupant, a ghost with a rather curious request, which sets the visitor careering from the house in terror. In “The Open Window” by Saki (Hector Hugh Munro), we are taught that some ghost stories do not even require ghosts to truly frighten the unwary visitor out of his wits.

Terror also lurks outside the walls of these mansions and castles. Writing about Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House, Stephen King alighted on the notion of “the bad place,” which he uses successfully in novels like Pet Sematary and The Shining. We find many such bad places in these pages. In Algernon Blackwood’s masterful story “The Willows,” two friends, who stop to camp for the night on a small island while canoeing down the Danube, begin to suspect that they are not alone. The willows themselves seem to moan and move of their own accord. While the friends sleep, one of their oars disappears, and a hole is scored in the bottom of the canoe. Other things begin to go wrong. They realize that the barrier between their world and another one has become porous and that something is trying to reach them, something older than the world’s religions. They begin to experience the presence “of a deliberate and malefic purpose, resentful of our audacious intrusion into their breeding-place; whereas my friend threw it into the unoriginal form at first of a trespass on some ancient shrine, some place where the old gods still held sway, where the emotional forces of former worshippers still clung, and the ancestral portion of him yielded to the old pagan spell.”

One tells the other that it might be “a question wholly of the mind, and the less we think about them the better our chance of escape. Above all, don’t think, for what you think happens!” Here we see yet again how menacing surroundings are reflected as the inner horrors felt by the visitors to these places. The greatest horror is always psychological.

Keeping Company with the Dead

No survey of “bad places” would be complete without a visit to desolate tombs and graveyards. There is no better place to start than with H. P. Lovecraft’s unnerving story “The Tomb,” about a sensitive and aloof young man who feels uncannily drawn to an old tomb he discovers near his house. In time, he finds he feels at home there. Lovecraft’s description of his character’s first visit rivals the opening of Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher.”

When, upon forcing my way between two savage clumps of briers, I suddenly encountered the entrance of the vault, I had no knowledge of what I had discovered. The dark blocks of granite, the door so curiously ajar, and the funereal carvings above the arch, aroused in me no associations of mournful or terrible character. Of graves and tombs I knew and imagined much, but had on account of my peculiar temperament been kept from all personal contact with churchyards and cemeteries. The strange stone house on the woodland slope was to me only a source of interest and speculation; and its cold, damp interior, into which I vainly peered through the aperture so tantalisingly left, contained for me no hint of death or decay. But in that instant of curiosity was born the madly unreasoning desire which has brought me to this hell of confinement.

In “An Inhabitant of Carcosa,” Ambrose Bierce delivers a ghost story told from a strange perspective, set in a desolate necropolis and allegedly told through “the facts imparted to the medium Bayrolles by the spirit Hoseib Alar Robardin.” The narrator cannot fathom why no one responds to his calls or seems to see him. Then he begins to wonder who the real ghost might be, prefiguring Bruce Willis’s role as Dr. Malcolm Crowe in M. Night Shyamalan’s 1999 film The Sixth Sense. “An Inhabitant of Carcosa” dovetails with Lovecraft’s “The Outsider,” whose narrator believes he has escaped from his ancestral home, where he lived in “dismal chambers with brown hangings and maddening rows of antique books . . . twilight groves of grotesque, gigantic, and vine-encumbered trees that silently wave twisted branches far aloft. Such a lot the gods gave to me—to me, the dazed, the disappointed; the barren, the broken.” When he enters a crowded ballroom, its inhabitants flee in terror.

Flight was universal, and in the clamour and panic several fell in a swoon and were dragged away by their madly fleeing companions. Many covered their eyes with their hands, and plunged blindly and awkwardly in their race to escape; overturning furniture and stumbling against the walls before they managed to reach one of the many doors.

He then believes he too can see the source of their terror and decides to approach it. Lovecraft’s surprise ending is unforgettable.

Such graveyards are home not only to ghosts but to grave robbers as well, or “resurrection men” as they were sometimes known. In nineteenth-century Britain, surgical colleges were filled with eager young students hoping to hone their skills on cadavers. According to government edict, however, only the bodies of executed criminals were to be used for this purpose. The result was a brisk demand and only a trickling supply. It was inevitable that someone would step in to meet the need. In Bierce’s “One Summer Night,” young medical students are greeted with a gruesome surprise in the graveyard, only to be shocked even further when they return to their dissection room the next day. Famous for his novels Treasure Island and Kidnapped, as well as his tale of split personality, The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Robert Louis Stevenson also dabbled in gore and ghosts. In “The Body-Snatcher,” a dissolute medical student is tasked with rising before dawn to pay for recently unearthed cadavers delivered by repellent, mud-stained men. He expects the cadavers to be disinterred from local cemeteries, but he begins to wonder why they seem to be so fresh. When he recognizes in one of the cadavers a friend whom he had seen alive only the day before, he realizes that something is terribly wrong.

A Fiend for All Seasons

Considering how popular vampires are today, one might be tempted to think they had always prowled the pages of literature. The vampire first seized the public’s imagination when Lord Byron published his poem “The Giaour” in 1813. Six years later, and fully seventy-eight years before Bram Stoker unleashed his swarthy Carpathian count onto an unsuspecting world, Byron’s personal physician, John William Polidori, published “The Vampyre,” which Christopher Frayling describes as “the first story successfully to fuse the disparate elements of vampirism into a coherent literary genre.” His story, inspired by both Byron and his poem, lavishes much attention on a suave British nobleman-vampire named Lord Ruthven. (Polidori’s story was also encouraged, in part, by the unfinished Byron story “The Burial: A Fragment.”) Polidori gives us the first neck-biter: “Upon her neck and breast was blood, and upon her throat were the marks of teeth having opened the vein.” “The Vampyre” was begun on the same rainy evening that Mary Shelley first imagined Dr. Frankenstein and his creature (the two authors, along with Lord Byron and Mary’s husband Percy Bysshe Shelley, whiled away the hours at the Villa Diodati near Lake Geneva during the torrential summer rains by telling each other ghost stories). “The Vampyre” embodies eternal anxieties about infection, foreign interlopers, and repressed sexual desire, thereby setting the standard for the modern vampire story.

Beginning in 1845, James Malcolm Rymer published a sensational and very long Gothic novel in parts (issued one chapter at a time in pamphlet form) called Varney the Vampire; or, the Feast of Blood, but the most famous vampire story appeared in the shape of Bram Stoker’s rambling 1897 novel Dracula. Stoker’s chronicle of an ancient and immortal Transylvanian count enjoyed fantastic success. Like many popular novels at the time, it was adapted for the stages of London’s West End and later New York’s Broadway, where a young immigrant actor named Bela Lugosi was discovered on opening night by a Universal Pictures scout and hired on the spot to play the count in the pioneering 1931 motion picture. Universal’s Dracula revived the paraphernalia of the Gothic tradition for the silver screen. Dracula’s castle, with its crumbling curved stairways, candelabras, vast spiderwebs, long shadows, and misty crypt, would be used again in innumerable horror movies, comics, novels, and Halloween haunted houses.

Two years after his death in 1912, Stoker’s widow published a collection of his stories, called Dracula’s Guest and Other Weird Stories, claiming that the title story was a “hitherto unpublished episode from Dracula . . . originally excised owing to the length of the book.” It is as terrifying as anything in Dracula. However, “Dracula’s Guest” differs from the novel on several counts. It is a straightforward, first-person narrative, while the novel relies on correspondence, newspaper articles, and private diaries to tell the story of Jonathan and Mina Harker, Lucy Westenra, Dr. Abraham Van Helsing, and the great vampire. The central character of “Dracula’s Guest,” an Englishman, is not named, though he is most certainly Jonathan Harker. Against the advice of the German hotelier, he decides to go out into the countryside on “Walpurgis nacht . . . when, according to the belief of millions of people, the devil was abroad.” He is even so bold as to leave his carriage and driver behind in order to explore the landscape on his own. Before he does, though, he and the driver, whose grasp of the English language is decidedly meager, indulge in a brief exchange on the merits of his decision to go wandering.

“Tell me,” I said, “about this place where the road leads,” and I pointed down.

Again he crossed himself and mumbled a prayer, before he answered, “It is unholy.”

“What is unholy?” I enquired.

“The village.”

“Then there is a village?”

“No, no. No one lives there hundreds of years.” My curiosity was piqued. “But you said there was a village.”

“There was.”

“Where is it now?”

Whereupon he burst out into a long story in German and English, so mixed up that I could not quite understand exactly what he said, but roughly I gathered that long ago, hundreds of years, men had died there and been buried in their graves; and sounds were heard under the clay, and when the graves were opened, men and women were found rosy with life, and their mouths red with blood.

After hearing this, our intrepid (some might suggest foolish) Englishman proceeds to make his way down into the dark valley during a snowstorm.

Lovecraft regarded Guy de Maupassant’s “The Horla” (1887) as a masterpiece, as it astonishingly combines science fiction, vampire fiction, and ghost stories in a single, unnerving tale. Through a sequence of diary entries, our narrator tells how he comes to suspect an invisible presence in his midst. Milk and water mysteriously disappear from sealed bottles. The narrator begins to believe that the invisible presence is starting to take control of his mind. He reads in the Revue du Monde Scientifique that

Information of a curious nature comes to us from Rio de Janeiro. An epidemic of madness, comparable to those contagious crazes which attacked the European peoples during the Middle Ages, is, it seems, at present, raging in the province of San Paulo. The inhabitants are leaving their houses in dismay, deserting their villages, and abandoning their crops, maintaining that they are being pursued, taken possession of, governed like a human herd of cattle, by certain invisible but tangible beings, resembling vampires, who suck upon their life-blood during their sleep, and who, besides that, take water and milk, but no other nourishment.

Maupassant leaves us to wonder what these “new” life-forms are, or if they exist at all. Are they vampires, ghosts, or merely mass hallucinations?

The fears of invasion and infection Maupassant explores in “The Horla” reach their purest form in Poe’s “The Masque of the Red Death.” When the Red Death, a virus even more horrific and contagious than the Black Plague, spreads into his kingdom, a wealthy prince invites his friends to retreat with him to a well-stocked villa where they can wait out the disease while enjoying endless parties. The revelries go on night and day with no expense spared and not a worry expended, until the prince is angered by the presence of someone he does not remember inviting, who arrives at the masque costumed as a victim of the dreaded Red Death.

Biological Perils

Fear of infection is linked with that of poisoning, as we find in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s “Rappaccini’s Daughter.” A naive student falls in love with a young woman he observes tending the “gorgeously magnificent” yet “strange” flowers in the garden below his window. Oddly, her father, Rappaccini, a scientist, is seen handling the same flowers with thick gloves and a mask to cover his face. When the student inquires about Rappaccini, a fellow scientist explains that Rappaccini “cares infinitely more for science than for mankind. His patients are interesting to him only as subjects for some new experiment. He would sacrifice human life, his own among the rest, or whatever else was dearest to him, for the sake of adding so much as a grain of mustard-seed to the great heap of his accumulated knowledge.” In this, he resembles Mary Shelley’s Dr. Frankenstein. In fact, “Rappaccini’s Daughter” also qualifies as a mad scientist story when it becomes apparent that Rappaccini’s most sinister experiment is his own beautiful daughter.

While one’s body can be easily poisoned, one’s mind may also be contaminated. Nathaniel Hawthorne’s “Young Goodman Brown” stumbles upon what he believes to be a Black Mass during his evening stroll deep in the woods outside of Salem, but he is not sure he can trust his eyes.

Either the sudden gleams of light flashing over the obscure field bedazzled Goodman Brown, or he recognized a score of the church members of Salem village famous for their especial sanctity. Good old Deacon Gookin had arrived, and waited at the skirts of that venerable saint, his revered pastor. But, irreverently consorting with these grave, reputable, and pious people, these elders of the church, these chaste dames and dewy virgins, there were men of dissolute lives and women of spotted fame, wretches given over to all mean and filthy vice, and suspected even of horrid crimes. It was strange to see that the good shrank not from the wicked, nor were the sinners abashed by the saints.

Are his fellow citizens, including his chaste wife, really secret worshippers of the devil? Hawthorne’s great-great-grandfather was a judge at the infamous Salem witch trials. One can’t help but notice how this played upon the author’s conscience. Part of the story’s terror stems from its ambiguity—a complexity that inspired Herman Melville to declare that the story is “as deep as Dante”—though ultimately the experience, actual or imagined, results in a very real, and heartrending, loss of faith for Goodman Brown, condemning him to a life of dejection and withdrawal.

In “The Devil and Tom Walker,” Washington Irving adopts a different approach to dealings with the devil, reminding the reader that when you strike a deal with the cloven-hoofed one, payment will come due eventually. A local merchant—a despicably greedy man—and his equally vile wife wonder if they are equal to doing business with the devil, hoping to profit where others have failed. When events turn against them, no one is surprised or saddened, and the “good people of Boston shook their heads and shrugged their shoulders, but had been so much accustomed to witches and goblins, and tricks of the devil, in all kinds of shapes, from the first settlement of the colony, that they were not so much horror-struck as might have been expected.” This is quite amusing. Supernatural events have become so common to New Englanders of the period that they greet such news with a complete absence of wonder.

Where there are devils, one will find demons of other orders. Balzac’s “The Succubus” appeared in Les Contes Drolatiques (Droll Stories), published serially from 1832 to 1837. These were tales of nymphomania and scatological pranks set in the Middle Ages and Renaissance, the author’s attempt to revive a tradition of robust, comic literature. Vampires may be cold, but Balzac’s succubus is sultry and irresistible. Among the vast host of hell, she is the sexy vixen. As he takes pains to explain, “Succubi or demons, having the faces of women, who, not wishing to return to hell, and having with them an insatiable fire, attempt to refresh and sustain themselves by sucking in souls.” Though concerning the demonic, the story borders on the comic, as the young woman accused of being a succubus proves to be as persuasive as she is seductive, leaving her accusers and interlocutors enamored and baffled, moving Christian knights to joust for her honor. Outrage and indignation are transformed into enchantment in her presence, though she comes to a gruesome end after confronting a sexless, ice-cold priest who is unmoved by her feminine wiles.

M.R. James may be the most accomplished author of Victorian English ghost stories, and, as we will see, the two stories in this collection also delve into the demonic. Like many horror authors, James prefers to relate stories second- or thirdhand, “as told to,” or discovered among old letters or diaries. Rather than muffling the horror, this technique actually makes it much more acute, as details become more vague and suggestive. In “Canon Alberic’s Scrap-book,” the narrator tells of an English scholar on vacation in the French village of St. Bertrand de Comminges who stumbles onto an opportunity to purchase a valuable volume of medieval manuscripts, though the seller seems downright eager to be rid of it at any price. As he leafs through its pages, he notices something disquieting in one of the miniature illustrations.

At first you saw only a mass of coarse, matted black hair; presently it was seen that this covered a body of fearful thinness, almost a skeleton, but with the muscles standing out like wires. The hands were of a dusky pallor, covered, like the body, with long, coarse hairs, and hideously taloned. The eyes, touched in with a burning yellow, had intensely black pupils, and were fixed upon the throned King with a look of beast-like hate. Imagine one of the awful bird-catching spiders of South America translated into human form, and endowed with intelligence just less than human, and you will have some faint conception of the terror inspired by the appalling effigy. One remark is universally made by those to whom I have shown the picture: “It was drawn from the life.”

He believes he is alone with his prized book but soon learns otherwise. In “Count Magnus,” another scholar (James served as provost of King’s College, Cambridge, and of Eton College) arrives to stay in an “ancient manor-house in Vestergothland” in Sweden, where he studies a venerable family’s history and finds himself fascinated by a distant ancestor who, it was whispered, had made something called a “Black Pilgrimage.” He finds himself asking, “What did the Count bring back with him?” He makes visits to the count’s sarcophagus in the family tomb. On his final visit, the lid begins to rise, causing him to hurriedly flee Sweden and his research. He begins to worry that he is trailed back to England by “two figures . . . in dark cloaks; the taller one wore a hat, the shorter a hood. He had no time to see their faces.” James placed his finger squarely on a particular type of horror. His characters find themselves unaccountably attracted to arcane or mysterious knowledge, only to find themselves visited by a long-buried menace. His scholars are killed by curiosity.

As we leave the world of devils, succubi, and demons behind, we enter a world of monstrous animals, some more loquacious than others. Poe’s classic “The Raven” is the sole poem in this anthology, highly memorable and memorizable, written in trochaic octameter, a very forceful, incantatory meter, with a short refrain at the end of each stanza. As with all of Poe’s verse, rhythms and rhymes entrance the reader. Poe’s raven appears to rise from the abyss, a messenger from another world. Like all ravens, he is capable of mimicking sounds from his environment, including human speech.

Then this ebony bird beguiling my sad fancy into smiling,

By the grave and stern decorum of the countenance it wore,

“Though thy crest be shorn and shaven, thou,” I said, “art sure no craven,

Ghastly grim and ancient raven wandering from the Nightly shore—

Tell me what thy lordly name is on the Night’s Plutonian shore!”

Quoth the raven “Nevermore.”

In “The Damned Thing,” Ambrose Bierce imagines an unseen creature altogether unknown to science.

There are sounds that we cannot hear. At either end of the scale are notes that stir no chord of that imperfect instrument, the human ear. They are too high or too grave . . . As with sounds, so with colours. At each end of the solar spectrum the chemist can detect the presence of what are known as “actinic” rays. They represent colours—integral colours in the composition of light—which we are unable to discern. The human eye is an imperfect instrument; its range is but a few octaves of the real “chromatic scale.” I am not mad; there are colours that we cannot see. And, God help me! the Damned Thing is of such a colour!

Monster animals come in all sizes. Arthur Conan Doyle, most famous for his character Sherlock Holmes, imagined massive, prehistoric creatures lurking beneath our world, rising up when the time is right.

All this country is hollow. Could you strike it with some gigantic hammer it would boom like a drum, or possibly cave in altogether and expose some huge subterranean sea. A great sea there must surely be, for on all sides the streams run into the mountain itself, never to reappear. There are gaps everywhere amid the rocks, and when you pass through them you find yourself in great caverns, which wind down into the bowels of the earth.

When a visitor to the limestone hills of North-West Derbyshire, in England, is told that sheep tend to go missing on pitch-black, overcast nights, he is overcome by curiosity and takes a bicycle lamp to explore an ancient Roman quarry and learn what might dwell in its depths.

Psychology and Terror

Most tales of horror depend in some way on the threat of madness and the surreal contours of psychological terror, but some raise these to such a fever pitch that they become a brand of story all their own. Stephen King has remarked that “the melodies of the horror tale are simple and repetitive, and they are melodies of disestablishment and disintegration.” We are fascinated by things going wrong, faulty memories, uncertain visions, those who steadily lose their grip on reality and begin to experience sublime moments of terror. Poe’s “The Pit and the Pendulum” conveys suspense to almost unbearable levels as the narrator, condemned to the fetid dungeons of Torquemada’s Spanish Inquisition, struggles to survive in the lightless, damp, rat-infested pit, only to face an almost unthinkable type of murderous technology.

Poe excelled at psychological tension. In fact, Lovecraft felt that Poe “clearly and realistically understood the natural basis of the horror-appeal and the correct mechanics of its achievement.” Poe’s “The Cask of Amontillado,” a tale of revenge and murder, is oddly comic, which makes it all the more disquieting (we cannot ignore the terrible irony of the victim’s name, Fortunato). Fortunato sings and laughs in a drunken reverie while he is slowly walled into his own tomb. It is worth noting that no fewer than four of the Poe stories included in this volume feature characters entombed or otherwise trapped in subterranean crypts, dungeons, walls, or under floorboards. Perhaps Poe’s most famous story is “The Tell-Tale Heart,” an account of heartless murder that results in hallucination, obsession, and lunacy. It seizes our attention at the very start.

True!—nervous—very, very dreadfully nervous I had been and am; but why will you say that I am mad? The disease had sharpened my senses—not destroyed—not dulled them. Above all was the sense of hearing acute. I heard all things in the heaven and in the earth. I heard many things in hell. How, then, am I mad? Hearken! and observe how healthily—how calmly I can tell you the whole story.

Poe places the story in the hands—and in the mind—of a truly deranged psyche. Even if we begin to believe the narrator’s claims, we are quickly disabused, disconcerted, and ultimately scared stiff. Poet and critic Daniel Hoffman wrote that “Poe was born to suffer, to thrill to the exquisite torment of those sufferings, to transmute them by his symbolistic imagination into paradigms of man’s divided nature.” Lovecraft himself—and he knew of whence he spoke—proclaimed that to Poe “we owe the modern horror-story in its final and perfected state.” All of this, and more, is on full display in “The Tell-Tale Heart.” Poe’s unreliable storyteller is so completely insane that he believes he can prove his sanity to us by explaining with what awful thoroughness and precision he carried out his terrible deed. He finally admits that he was called to confess by something he alone could hear.

All this talk of madness brings us to “The Yellow Wallpaper” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, which novelist and critic Lynne Sharon Schwartz described as a story about “a trapped woman’s mental disintegration.” After arriving in “a colonial mansion, a hereditary estate, I would say a haunted house,” where she has moved with her husband for three months in order to recuperate from “nervous depression,” the narrator becomes fixated on the hideous peeling wallpaper on the walls of the former attic nursery they choose for their bedroom.

One of those sprawling flamboyant patterns committing every artistic sin. It is dull enough to confuse the eye in following, pronounced enough to constantly irritate and provoke study, and when you follow the lame uncertain curves for a little distance they suddenly commit suicide—plunge off at outrageous angles, destroy themselves in unheard of contradictions. The color is repellent, almost revolting; a smouldering unclean yellow, strangely faded by the slow-turning sunlight.

She becomes convinced she can spot shifting patterns, like fungus, in the wallpaper, finally believing she sees a woman creeping behind the pattern, trying to get out.

While he is not typically grouped among horror writers, there is little question that Franz Kafka remains among the most terrifying of authors. In his story “In the Penal Colony,” a visitor to a distant land witnesses a meticulous demonstration of a monstrous machine—a “peculiar apparatus”—that slowly kills a condemned man by writing his very death sentence onto his skin with needles until he can finally feel the words before being allowed to die. Kafka’s stories contain such symbolic significance that they become allegories of the modern horrors experienced at the hands of totalitarian regimes of the twentieth century. “The Metamorphosis,” his most harrowing tale, contains one of the best opening passages in literature.

One morning, when Gregor Samsa woke from troubled dreams, he found himself transformed in his bed into a horrible vermin. He lay on his armour-like back, and if he lifted his head a little he could see his brown belly, slightly domed and divided by arches into stiff sections. The bedding was hardly able to cover it and seemed ready to slide off any moment. His many legs, pitifully thin compared with the size of the rest of him, waved about helplessly as he looked.

In the spirit of a true nightmare, Gregor is at first much more anxious about being late for work and disappointing his employer than in the fact that he’s been transformed into a giant insect. To make his morning even more nightmarish, a representative from his firm arrives to the apartment demanding to know why Gregor has not appeared for work, causing his mother, father, and sister to bang on the door pleading with him to come out. Once he finally manages to open the door, they are utterly repulsed by him. The story, strange as it may be, is actually heartbreaking, as poor Gregor can understand his family when they speak but he is unable to communicate in any way with them. Try as he may, he cannot explain that he is not a monster. It is deservedly ranked among the greatest stories of any kind and is the crown jewel of this collection.

Like science fiction, fantasy, and mystery, horror is a living art form, and it has never fallen entirely out of favor. It continues to occasion annual anthologies, conventions, comics, and, of course, the lasting attention of Hollywood. The stories in this anthology—spanning over a century, from Polidori’s “The Vampyre” in 1819 to Lovecraft’s “The Outsider” in 1926—paved the way for much that followed, including television shows like The Twilight Zone, Alfred Hitchcock Presents, The X-Files, and American Horror Story, not to mention the seemingly unstoppable waves of vampire books and films. While not all entries in this collection conform to the highest standards of literary art, they are, to a one, very accomplished stories in their own rights.

This collection, voluminous as it may be, is but the merest peek through a crack in the doorway. Many other worthy authors could have been included in these pages, including Joseph Sheridan LeFanu, Elizabeth Gaskell, Edward Bulwer-Lytton, Mary Elizabeth Braddon, Amelia Edwards, Margaret Oliphant, Sutherland Menzies, Lafcadio Hearn, Mary Austin, Mary Wilkins Freeman, and Robert Aickman. Likewise, many chilling novels fall outside the purview of this anthology due to their sheer size, such as Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights, H. Rider Haggard’s She, Arthur Machen’s The Great God Pan, and even Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey, which satirizes the faddishness of Gothic novels. All of these are worth seeking out, and one would be commended for continuing to explore these authors and helping to restore old stories that have unjustly fallen out of taste.

Why are we drawn back to these dark corners again and again? Some part of us likes to be scared. After reading these stories, we find ourselves starting at unexpected sounds, staring out into the dark, checking over our shoulders to see if we are being followed. They take away the illusion of comfort we allow ourselves in happier moments. Clive Barker, whose six short story collections, collectively titled The Books of Blood, reinvigorated the horror genre in the 1980s, insists that horror fiction “shows us that the control we believe we have is purely illusory, and that every moment we teeter on chaos and oblivion.” We would rightly banish horror stories from our lives if we did not believe he is correct. E. F. Benson wrote in the author’s preface to his story collection The Room in the Tower that he “fervently wishes his readers a few uncomfortable moments.” Indeed, as he points out, this is “the avowed object of ghost-stories and such tales as deal with the dim unseen forces which occasionally and perturbingly make themselves manifest.” So, by all means, settle in and make yourself uncomfortable. Curl up with this collection of disturbing tales—and take care to keep the lights burning and your friends close by.