My long essay on Robert Lowell’s late career blank-verse sonnets, or Notebook poems, appears in the new issue of Literary Matters. Those poems by Lowell exerted a potent influence on me when I composed my own first two books, both of which consist of 14-line poems that explore the boundaries of the contemporary sonnet (though mine rhyme). The issue includes further essays on Lowell by Florian Gargaillo, Henry Hart, Jenna Lê, Elise Partridge, and Joan Romano Shifflett as well as fiction by Carolyn Jack, translations by Tony Barnstone and Bilal Shaw, poems by Carl Dennis, Moira Egan, Juliana Gray, Mark Jarman, Stephen Kampa, Julie Kane, Katy Lederer, and much more.

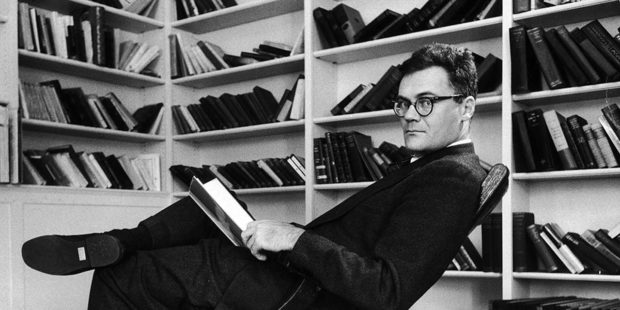

When Robert Lowell began writing the poems that would appear in the unusual and still controversial volume Notebook 1967-1968, he was generally celebrated as America’s most famous living poet. His patrician profile and the details of his personal life were familiar to any educated American. Time magazine hailed him as “America’s greatest poet.” What may strike some as odd in 2017, on the centenary of his birth, is the very notion of a genuinely famous poet, one who confidently dispatched letters of political protest to Presidents Franklin Roosevelt and Lyndon Johnson and expected replies. In other words, the world that formed Robert Lowell and heaped laurels upon his brow, including two Pulitzer Prizes, has changed dramatically and irrevocably.

In fact, the literary establishment that hailed his presence has almost ceased to exist in any meaningful way. Born the scion of a lesser branch of the famous New England Lowell family—true Boston Brahmins, when that still meant something—Lowell numbered among his relatives two other famous poets (Amy, who also won a Pulitzer Prize, and James Russell, one of the Fireside Poets) and Mary Chilton, who was the first woman off the Mayflower, along with a president of Harvard, a Civil War general, industrialists, federal judges, and an astronomer who helped discover Pluto. Like T.S. Eliot, Robinson Jeffers, and Robert Frost before him, Lowell appeared on the cover of Time magazine; however, Lowell’s appearance on the cover of the June 2nd, 1967 issue, with the headline “Poetry in an Age of Prose,” would mark the last time a poet would occupy that august position. Just as Time’s circulation continues to dwindle in the Internet age, Lowell’s position in the pantheon continues to slip. Pages allotted to his work in anthologies grow ever fewer. Many younger poets know him only (if at all) as one of the names associated with the school of Confessional Poetry (despite the fact that, as Frank Bidart notes, “he scorned the term”).i But it was not always so.

For Lowell, success came early, and, in its train, the sometimes difficult condition known as fame. Lowell’s first commercially published book, Lord Weary’s Castle (preceded by Land of Unlikeness, produced in a limited edition of only 250 copies by the Cummington Press in 1944), won the Pulitzer Prize in 1947 when the poet was only 30 years old. In the years that followed, he parlayed public fascination with details of his troubled and privileged life into what came to be known as the Confessional School of Poetry (Lowell taught W.D. Snodgrass, Sylvia Plath, and Anne Sexton and was close friends with John Berryman, the principal players in the group). Throughout his life Lowell suffered from bipolar disorder: long crescendos of mania, accompanied by periods of intense creativity and frequently troubling behavior, followed by aftermaths of terrible depression and regret. In the course of fifteen years, during which time he published his most important poems, Lowell was hospitalized no fewer than twelve times, often for extended periods. When reading biographies of Lowell, one not uncommonly encounters passages describing friends, colleagues, and police officers physically struggling to restrain the poet during a violent outburst.

Read on at Literary Matters.

No Comments